Advertisement

'Why I Write': 2014 Edition

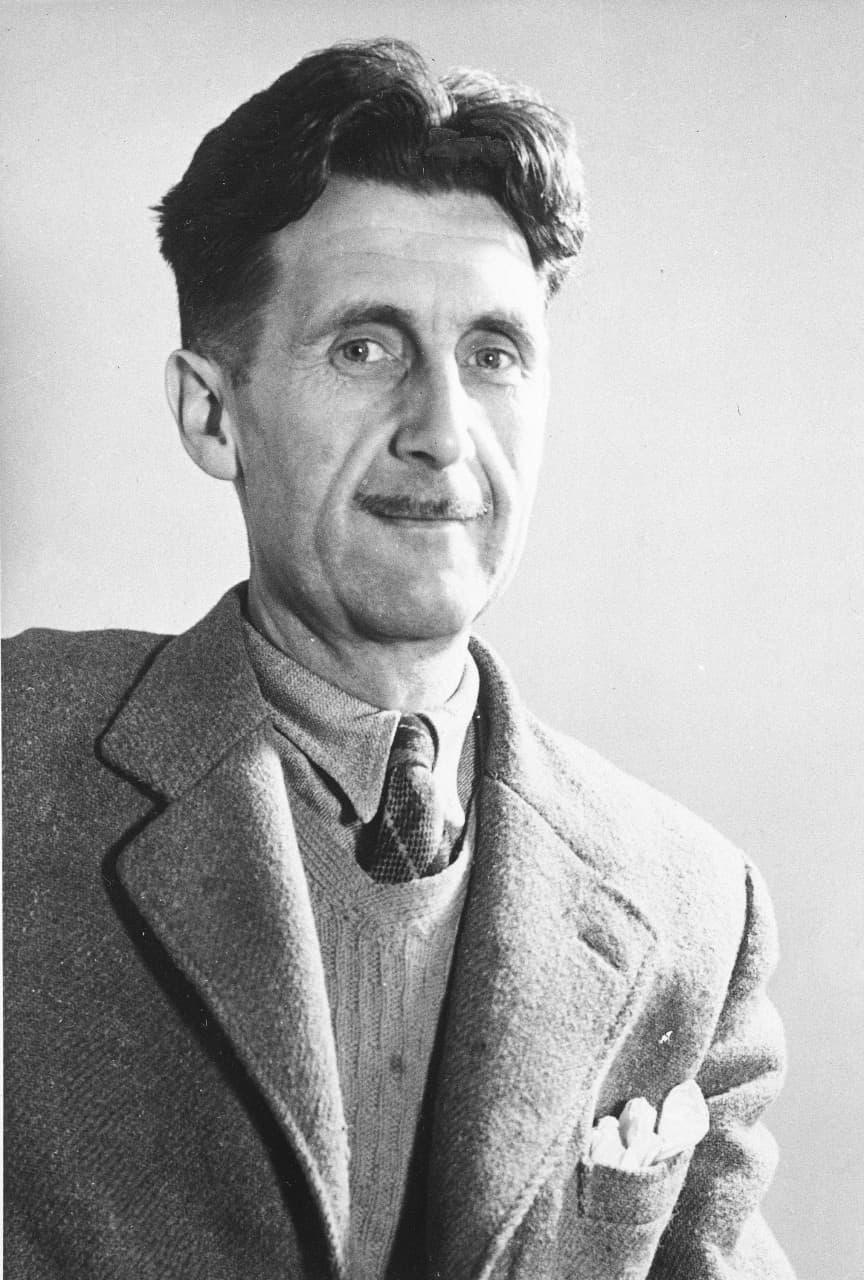

In 1946, George Orwell penned a famous essay titled “Why I Write.” It’s a wonderful and honest piece of work full of righteous goals and praiseworthy aims. I recommend it to anyone interested in literature, politics or the nexus where these subjects meet.

Recently over coffee, a friend asked me this same question. He listed a handful of reasons why, to anyone with a practical mind at least, writing seemed a pursuit bordering on the ludicrous. After all, I had a full-time job, wasn’t that enough to keep me busy and my liquor cabinet stocked?

His query set me to thinking. Indeed, today’s would-be authors asked to answer that same question might respond less rosily than Orwell did nearly 70 years ago. They might say, for instance: “I write because I enjoy patching together a meager existence and living assignment to assignment.” Or, “I write because I’ve always wanted to know what bankruptcy feels like.” Or maybe even, “I write because I choose to live wild and free, sans crazy extravagances like health insurance, life savings or reliable transportation.”

Isn’t there some virtue in leading the life of the starving artist? Of suffering for one’s art?

Writing does not pay as it used to, that’s for sure. This is especially true of those who write what’s known as literary fiction. While some authors make a decent living and a select few sleep on piles of money, most are forced to do it as a hobby or at least hold down a “real” job to pay the bills.

Consider this: seven out of 10 books don’t earn back their advance, according to a New York Times article from a few years ago. Even when that advance is the much-envied “six-figure” kind, after commission and taxes and extrapolated over the time it takes to write a book, that fat payday pans out to slightly above what a paper route might yield an ambitious teenager. As author Walter Kirn says in that same Times article, “A low-six-figure advance has allowed me to work at less than minimum wage for three years.”

If I sound a bit glum, perhaps it’s because I’ve just finished reading “MFA vs. NYC: The Two Cultures of American Fiction,” a new collection of essays that investigates the impact the rise of creative writing programs has had on today’s novelists, as well as the state of the publishing industry in general. A sad undercurrent running throughout the book is how even well-known, award-winning writers must struggle to get by.

The takeaway is either you’re Jonathan Franzen or you’re nobody.

“MFA vs. NYC” is actually a compelling read, full of well-argued points by writers who have spent much time over the past decade or more on the frontlines, trying to eke out a living with their wits and imagination, all the while battling that dreaded voice of reason that keeps asking: “Why are you doing this to yourself?” And by the way, by writers I mean Writers. Not the single mom who comes home from her dayshift, takes care of the family, and then works past midnight on the novel she hopes to one day self-publish, admirable as all that may be. No, the writers featured in this collection are the 1 percenters — those born to the mansion of fiction by virtue of early talent, expensive schooling, lucky breaks and preternatural perseverance. Thus reflected in these essays is an elite perspective that’s applicable to the select few. However, they’re fun nonetheless for allowing the rest of us a peak into how the chosen are doing.

It seems they are not doing well. For most authors, the days of big advances, hefty sales and a guaranteed livelihood are long gone. These days, nearly every author of serious fiction has to support him or herself by teaching, the upshot of which has been an explosion in degree-granting creative writing programs. In 1976, there were 79; today there are 1,269.

“MFA vs. NYC” makes the case that this jump has impacted all those involved. The teacher-authors are left with little time to write and, with that university paycheck in hand, rely less on publishing income. While the students learn to write in ways that please their esteemed professors and subsequently aspire not to writing great books but to making a living as part of the next cohort of writer-teachers. In this hermetic world, published novels become mere credentials.

On the flipside, for those who, with or without that MFA, feel they need to move to New York City to be close to the publishing world, they may end up going broke before they get a foot in the door, or else they tire of odd jobs and Ramen noodles long before their big break arrives. Hence, there’s increased pressure to write fiction that’s less original and daring and more saleable.

The lead-off essay in “MFA vs NYC” is by the book’s editor, Chad Harbach, author of the bestselling novel, “The Art of Fielding.” He outlines the different effects these two cultures have wrought on today’s fiction and its creators; subsequent essays fill in the rest of the story, with plenty of depressing anecdotes.

The takeaway is either you’re Jonathan Franzen or you’re nobody.

All this reminded me of a buddy of mine who spent his early years trying to write and play songs in the manner of his favorite folk and blues artists. “What am I doing with my life?” he asked one day. “Even my heroes aren’t that successful.”

Isn’t there some virtue in leading the life of the starving artist? Of suffering for one’s art? Of being the scribe who monomaniacally shuts himself away, shuns the dictates of the market, and does his best to put down the truth as only he knows it? I remain hopeful: Perhaps today’s telemarketer is tomorrow’s Tolstoy.

So, what did I tell my friend the other day when he asked me why I write? I simply shrugged and said, "I can’t stop."

Related: