Advertisement

Guilt Trip: What Happens When Unearned Shame Meets Undeserved Suffering?

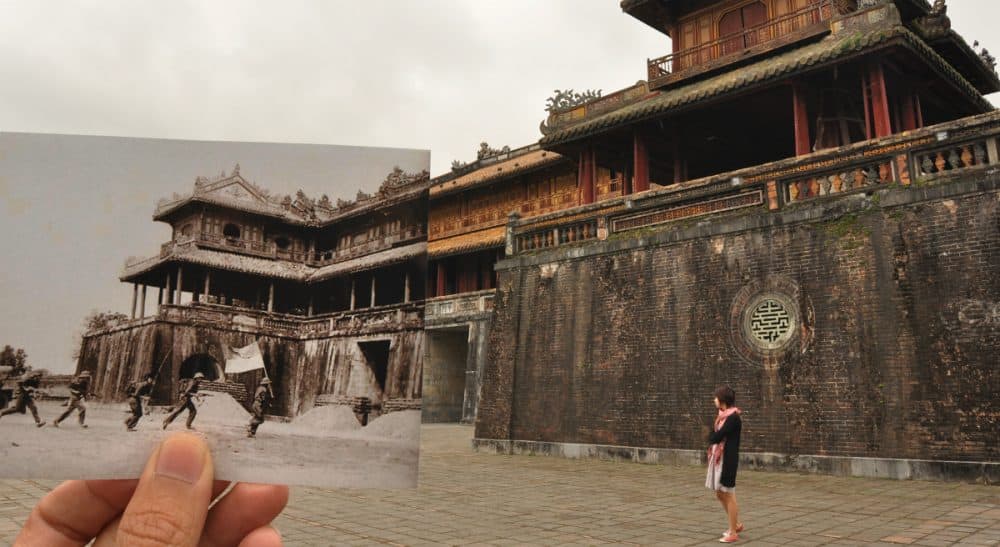

I’m showing Becky, my friend since we were high school students together in 1968, pictures from a recent trip my husband and I took to Vietnam.

A woman in a conical hat squats in a pile of rubble amidst trays of mustard greens and cilantro, basil and cabbage.

“Did we do that?” Becky asks.

I know exactly what she’s asking. This mass of debris — a mound of concrete chunks and twisted metal — look like the remains of a bombed-out building. The alley housing it — a dusty, narrow, ruin-filled lane — was around the block from our Hanoi hotel. And just like Becky, my first thought when we rounded the corner was that I was seeing a building that American forces had bombed.

So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence.

Susan Sontag

I had to remind myself that the war had ended 40 years ago. Chances were pretty good that the North Vietnamese had cleaned up the rubble since then. Indeed, as the day progressed and we wandered through more of Hanoi, it became clear that this alley was an anomaly, the rocky heap evidence of nothing more than a routine site of urban renewal. And though the street food chefs and coffee bar baristas, the taxi drivers and hotel staff we met are undoubtedly schooled in the country’s history of anti-colonialism and war, the fighting was over before many of them were born.

Becky and I could laugh at our knee-jerk response, our reactions at age 60 dictated by what dominated our consciousness at 16. But as a Jew, I know that it takes more than one generation to forget or to move on from suffering on such a massive scale. And as an American, I couldn’t help but feel accountable for my government’s actions those decades ago, for wasting hundreds of thousands of lives in support of the sanctimonious, self-serving ideology espoused by the war’s architect, John Foster Dulles: “For us there are two kinds of people in the world. There are those who are Christians and support free enterprise, and there are the others.”

Though I’d vigorously protested the war in my youth, the fact remained that even now, I was the affluent tourist taking photos of the lean people working six days a week, carrying their livelihoods quite literally on their backs.

And one short flight away, in Cambodia, that gap between the haves and have-nots was even more visibly and painfully apparent.

“We are a victim country,” our guide Borin told us. As he escorted us through the breathtaking temples in and around Angkor Wat, he matter-of-factly explained that for years, the landmines laid around these breathtaking historic sites made tourism impossible. Cambodia’s war didn’t end in 1975; that year marked just the beginning of another five years of horrific suffering under the Khmer Rouge.

We saw people casting nets for fish in a river so filthy that I dared not even touch the water, living in three-walled huts, trudging along dusty roads in the equivalent of drugstore flip-flops. We heard stories of famine, dismemberment, resettlement, torture and genocide. This is a country where less than 4 percent of the population is over the age of 65, one-third the ratio of the elderly in the United States. There are so few old people because so many of that generation were killed.

Borin grew up desperately poor, and had to walk the 10 kilometers to school from his peasant home because his family lacked even the means for a bicycle.

We may not be able to atone for the needless, futile punishment inflicted by political zealots from generations past. But we can look and listen.

“I was ashamed,” he told us, “so I became a runner. That way I could jog to school and tell my classmates that I was training.” He moved to the city and lived in a Buddhist monastery and even while working, he didn’t earn enough to afford a home. Even now, he and his wife and daughter live with his brother and sister-in-law and their children in a single room, relieved to simply have a roof over their heads and rice to eat.

His storytelling is fluent. I’m sure he’s told these tales of woe to many of his clients, maybe even with the goal of winning a bigger tip. And as hardship tourists, perhaps we were even complicit in this dance. After all, as Susan Sontag wrote, “So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence.”

But that doesn’t make these accounts false or unworthy of our attention. So when a young American lawyer on our bus from Vietnam’s Halong Bay complained that it was tiresome to hear tales of Cambodian woe, I reacted with barely suppressed rage.

We may not be able to atone for the needless, futile punishment inflicted by political zealots from generations past. But we can look and listen. We can start to honor the suffering of others, maybe even prevent it, by doing our best to bear witness.