Advertisement

A Tale Of Two Cubas: Why An Exile Still Won't Return

For the past half-century, my mother has desperately missed her native Cuba.

Yet the recent and stunning reversal of Washington’s long-time policy towards Havana has left her resolute that the Americans are coddling the Castro brothers’ dictatorship. Cuba is still as closed to her as the day my grandmother, after an extended stay to take care of me, her newborn grandchild, boarded one of the last commercial flights from New York to Havana in 1961.

“I’ll never set foot in my country as long as Fidel and Raul are in charge,” says my mother with an exile’s fervor. She wants the doors to open to the Cuba she once knew, not the country she sees as grotesquely frozen in time. When I show her pictures that I took just a few years ago of her house on La Callé Merced in Old Havana, she weeps.

My mother epitomizes the suffering of her fellow Cuban exiles. I first saw it as a little girl, when she stood at our kitchen window in Connecticut and moaned, “Hay Cuba como te estraño.” For my mother’s sake, I missed Cuba too, even though I had never been there.

The closest I got to Cuba back then was Little Havana in Miami. I was 9-years-old the first time my mother took me there. It was 1970; the height of Cuba’s isolation, and my family was hungry for news of our relatives trapped on the island. We headed towards the dull neon of my cousin Estersita’s Miami Beach neighborhood. All I knew about her and my other Cuban relatives was that they had escaped from Castro’s oppressive regime a few years earlier. They settled near Lincoln Road, among other anti-Castro Cubans, while waiting to return to Havana.

Every morning in Little Havana, my mother treated Estersita and her family to café con leche and eggs at the Cuban diner. She slathered our pan Cubano with butter the same way she applied our suntan lotion against the strong Miami sun.

My mother, who immigrated in 1958, was the first in her family to come to the United States. She married my American Dad a couple of years later. No one in my mother’s family had ever married out of its Sephardic-Jewish-Latino constellation. In Miami, she played the role of an affluent Americano’s wife in earnest, never letting on that she and Dad had separated.

Like my relatives who pined for Havana, I waited for a sign that my father had not forgotten me. I hoarded dimes to call him in secret from a payphone around the corner.

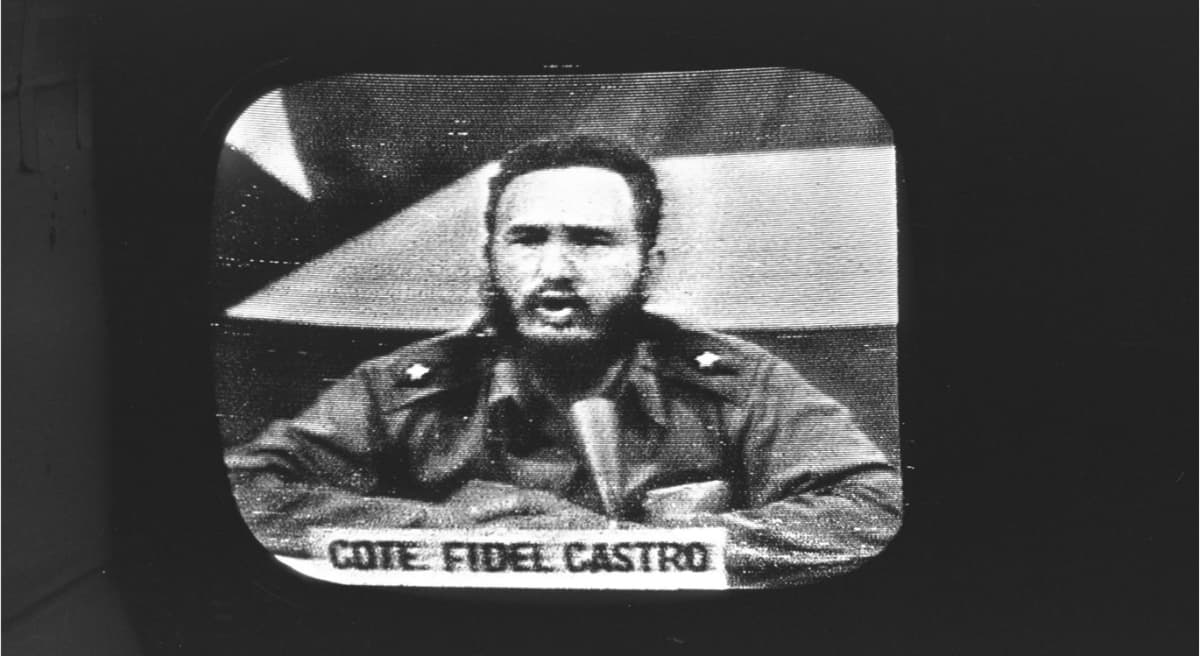

In the evenings, I sat in the living room of my relatives’ small apartment as Estersita’s husband Pepé adjusted the rabbit ears on the television. The electronic snow gave way to a fuzzy picture of Castro with his woolly, raggedy beard. Castro, in his drab military uniform and lidded cap, spoke in one long streak of breath, like the Cubans I knew in Miami. “Patria o muerte! Venceremos!” — "Fatherland or death! We shall overcome!" he said. Pepé and his poker buddies screamed, “Hijo de mala madre” — "son of a bitch" — at the screen. The ladies at Estersita’s kitchen table, where she gave manicures in front of Spanish soap operas, novelas, during the day, joined the men in cursing the television.

Castro jabbed an index finger in the air. The broadcasting interference made him sound as if he were hoarse. Yet he spoke in a pellucid Spanish that came to us all the way from La Plaza de la Revolución.

I got up for more ice cream, and just as I passed the television, the room burst into exclamation. “Para!” One of the poker players screamed at me to stop. “No te mueves!” — "Don't move!" I had stumbled upon the sweet spot in the room where the reception happened to be perfect. I, the Americanita, had brought Fidel Castro into focus. They watched him with the same curiosity with which one gawks at an accident.

“Por Dios,” cried my mother. “Castro talks forever. La niña can’t stand there all night.”

“She can for 10 cents an hour,” Pepé bellowed.

My mother epitomizes the suffering of her fellow Cuban exiles.

From then on, night after night, in real time, I was a human antenna, catching signals from Cuba.

When I arrived in Miami, I spoke a clunky, simple Spanish that Estersita and the others thought sounded funny. I struggled to read menus and understand the novelas. But with each passing day, I slipped deeper into the language until one day, when I realized that I understood Castro without first having to translate him in my head. I was becoming fluent but tried to stop myself from sliding completely from American to Cuban, from two parents to one.

I finally collected enough dimes to call my father a thousand miles away in Connecticut. When I got him on the line, he called me sweetheart and promised to come down to see me. A few weeks later, he made good on his word. We packed our bags and left Little Havana to move into a fancy motel on Collins Avenue for the occasion. My parents reconciled, and we went north to a place where Castro was once again a silent picture in the newspaper. No longer just 90 miles away from Cuba, we were north, where my mother will always miss the Cuba that was.