Advertisement

Rand Paul's World: Why His Greatest Strength Is Also His Achilles' Heel

Will Rand Paul be the next throwaway into the bin of former Republican presidential candidates? The Kentucky senator is bottom-feeding in polls and faces possible exclusion from the main event at the next GOP debate Oct. 28. Some poo-bahs of punditry predict that the libertarian Paul will soon exit the race, crippled in large measure by his less aggressive, Obama-like foreign policy, which casts a skeptical gaze at American military interventions advocated by his Republican competitors and national security-minded party members.

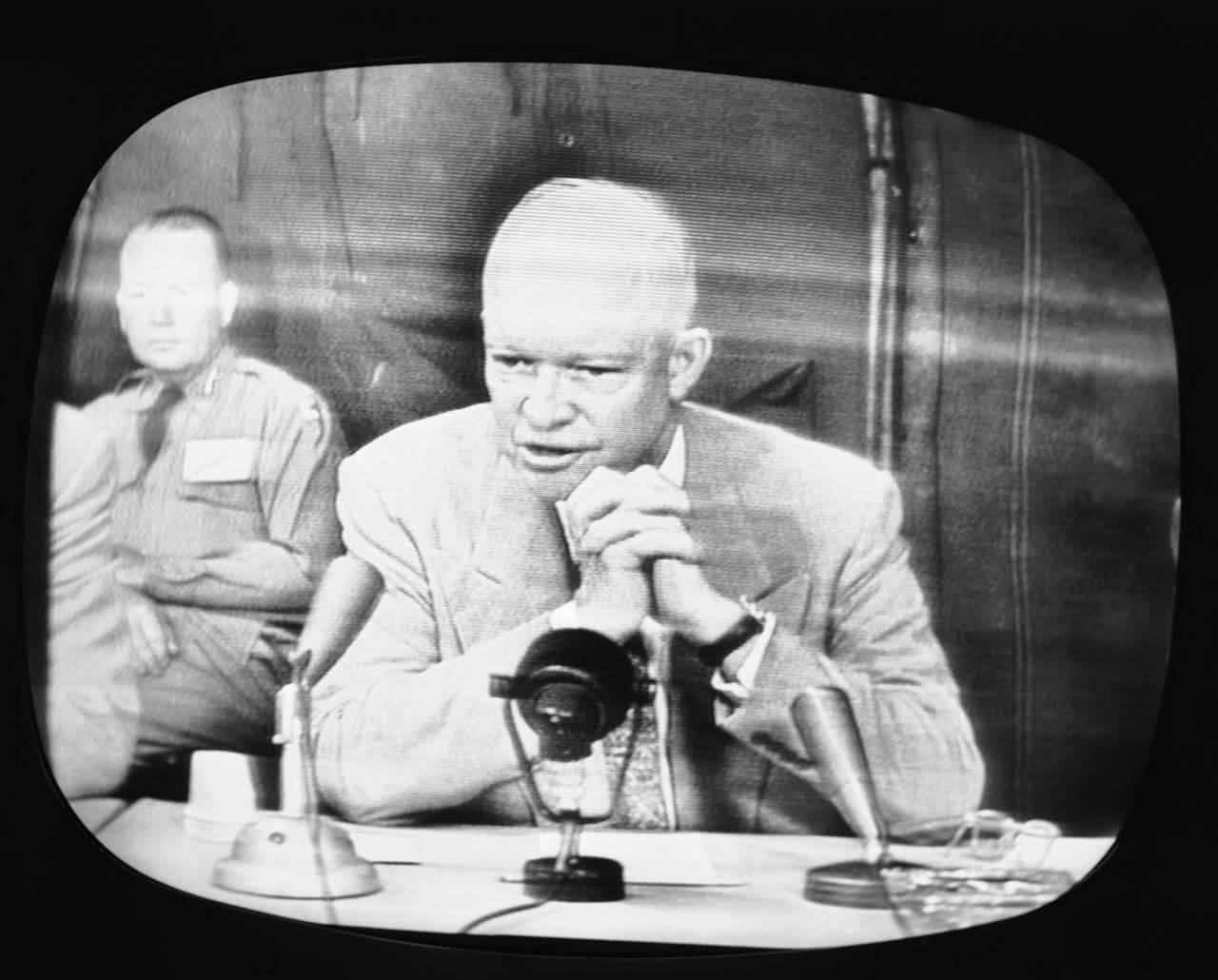

I’m no fan of Paul’s heedless libertarian economics and won’t drench a hanky if he decides 2016 isn’t his year. But I do hope the chest-thumpers in our shared party think long and hard about his (and Obama's) view of the world, for it’s the one embraced by a Republican general-turned-president in one of his finest moments. More than half a century before Obama’s White House summed up its foreign policy as “don’t do stupid sh--,” Dwight Eisenhower, following the same doctrine, passed on a war into which his Democratic successors would stumble, with devastating results.

Some poo-bahs of punditry predict that the libertarian Paul will soon exit the race, crippled in large measure by his less aggressive, Obama-like foreign policy...

In 1954, the Eisenhower administration faced a decision whether to aid the beleaguered French military, who, after a decade of war, were on the verge of being ejected from Vietnam by communist rebels. The United States had spent billions trying to bolster the French position, to no avail; now France was demanding we intervene to save a garrison pinned down in Dien Bien Phu. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, the Army chief of staff and a veteran of World War II and Korea, sent a team to Indochina to determine what a land war would require.

“The answers were chilling,” David Halberstam recounted in his acclaimed book, "The Best and the Brightest": “minimal, five divisions and up to ten divisions if we wanted to clear out the enemy (as opposed to six divisions in Korea), plus fifty-five engineering battalions, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 men, plus enormous construction costs” in a land devoid of highways, railroads, or phone lines. Eisenhower, who knew the horrors of war (and was allergic to unbalanced budgets), abandoned any notion of going in.

Halberstam documents how Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, lacking candid military analysis like Ridgway’s and Eisenhower’s willingness to consult allies and Congress, subsequently plunged into Vietnam. A losing war that killed and maimed a generation of Americans — not to mention many more Vietnamese — and sundered the nation failed in its goal of enhancing our security.

Yet Paul’s Ike-like wariness of military adventurism is “more frightening than any prominent Democrat, save Sen. Sanders,” an Iowa Republican groused to Politico.

Really? The Kentuckian supported negotiations to derail Iran’s nuclear aspirations, which produced a deal in our national interest. He endorsed Obama’s opening relations with Cuba — again the right call, reversing decades of impotent cold-shoulder-ing. “Let’s overwhelm the Castro regime with iPhones, iPads, American cars and American ingenuity,” Paul said of a time-tested strategy. (Just ask those Canadians who resent the flood of U.S. stuff their countrymen buy.) This engagement with the world is the opposite of isolationism, the dig against extreme libertarian views.

It’s true that Paul doesn’t swoon over military engagement like other Republicans do. He criticized the American war in Iraq. I supported the war because I thought Saddam Hussein likely had or was close to getting weapons of mass destruction. Paul was right; I was wrong, and most Americans now agree the war was a catastrophe. The senator also thought intervening in Libya to help remove Moammar Gadhafi’s tyranny was a mistake; Obama, who oversaw that intervention, only to see chaos engulf that nation, later admitted as much. Paul has urged a hang-back posture in the Syrian civil war. Republicans fault Obama for similar hesitancy — sitting on his thumbs while ISIS, fighting the Syrian regime, grows ever stronger, they say. But New York Times foreign affairs columnist Thomas Friedman sees wisdom in this discretion, now that Russia has intervened to support the Syrian regime. Russian leader Vladimir Putin will only antagonize the majority Sunni Syrians oppressed by the regime while battling jihadists who can be beaten only by “some miracle,” Friedman wrote.

I think we have to think before we act, and understand that intervention doesn’t always achieve the intended consequences.

Sen. Rand Paul

Paul and Obama are not pacifists. They believe that when you’re attacked or seriously threatened, you fight. Obama probably didn’t foresee, running his first race for the White House, that he’d outdo George W. Bush in drone attacks. Moreover, there are cases in which military means can achieve noble ends with minimal risk. President Clinton confessed error in not stopping the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and Friedman’s Times colleague, Nicholas Kristof, lists almost a half dozen instances of soldiers saving innocents in humanitarian interventions, including in Bosnia and Kosovo.

If the polls are right, we’ll never find out how a President Paul would handle similar crises. But his critics aren’t goading him about such low-threat propositions but about the Middle East, a tragic charnel pit where the good guys in war can be hard to come by. As Paul said of Syria, “I think we have to think before we act, and understand that intervention doesn’t always achieve the intended consequences.” Eisenhower and Ridgway would have agreed.