Advertisement

The City Of Light Plunged Into Darkness

A note from the editors: We are pleased to share the following op-ed by special guest contributor, French scholar Fabien Jobard. Below, we present the piece in English, followed by the French. The English translation is by Cognoscenti editor, Kelly Horan.

...

In the face of terror, it is said often and in all languages: “Words fail me.” When at last the words come, they are ones that cast the devastating act beyond the realm of reason and civilization. Monday, French President François Hollande used the words “madness” and “barbarity” to describe the attacks in Paris. These words reassure us, in a certain sense, because they separate and order our world – there are those capable of madness, and those who remain grounded in reason.

But what became so quickly apparent last Friday night was the very organized, planned and rational nature of the attacks – characteristics that line up poorly with the idea that they were borne of a lack of reason. Parisians in particular discovered the extent to which the terrorists demonstrated a perfect command of the political and social geography of their city.

Parisians in particular discovered the extent to which the terrorists demonstrated a perfect command of the political and social geography of their city.

The attacks targeted a very narrow segment of Parisian society: the highly educated, 30- and 40-something bourgeoisie, young men and women open to the world, who fought in support of gay marriage, for example, and who, at the start of this century, helped nudge City Hall to the left.

The heavy-hearted disbelief that hangs over Paris since the attacks is even greater than that which came in the wake of the attacks on Charlie Hebdo. Why? Whereas the victims in the Charlie Hebdo massacre were targeted for what they allegedly did, those murdered last Friday were targeted for who they were, for how and where they lived. Many journalists who covered the attacks (from Le Monde, Libération, Médiapart, among others) witnessed the killing from their own flats overlooking the scenes.

Like them, I can’t look at last Friday’s attacks but through the lens of familiarity – geographic, but social, too. I lived two blocks from Bataclan, where I spent many nights out. I often had lunch at Le Petit Cambodge. The rue Bichat, where some of the killings took place, is the same street where many of the meetings of Vacarme, a political revue I write for, are often held.

Paris may well be a city of “unsurpassed beauty,” but it is also a city made up of vastly segregated areas. While playing out against the backdrop of the destruction wrought by American power in Iraq and across the Middle East, the killing is part and parcel of a class struggle that is ongoing in Paris today, one rooted in deep territorial polarization.

So if there is a class struggle in Paris, why go after this fraction of the population? Very simply, because it’s this group the terrorists most revile. It’s this group that embodies and makes possible inclusiveness, cosmopolitanism and a mix of cultural reference points. It is a class that cares not just about its own needs, but the needs of others.

Out of this young and festive crowd of who died in Bataclan’s theater was Matthieu Giroud, who taught literacy to homeless children – some of whose parents were forced out of their homes by soaring Paris real estate. Another, an Italian PhD student, Valeria Solesin, worked with Emergency NGO, helping victims of foreign wars.

It is a class that socializes with the same young Arabs and Africans seen as apostates by fanatics. Like Sarajevo during the war in Yugoslavia, this segment of the population represents the promise of an integrated world even as it crystallizes the hatred of those who wish to destroy it.

But this fraction of the population also provoked the hatred, verbal this time, of conservative members of the French bourgeoisie who accused them of being "Bobo" narcissists enclosed in their rich ghetto and private schools, of investing more worry in Nepal or the deprived French suburbs than in the plights of so-called "real French people" in the countryside and small forgotten villages of their own country. The attacks have been the stuff of neo-conservative bestsellers in France in recent years, echoing — without avowing — reactionary and Fascist themes heard in the 1930s, which also cast the celebrated countryside -- the "real France' — against the cosmopolitan perversion of Paris. Their guilt-ascribing diatribes have but one intention: the closing of France in on itself, the closing of its borders. Theirs is the concern of a 'self' that excludes the rest of the world.

The massacre of this young bourgeoisie offers proof to the enemies of inclusiveness, to the enemies of openness to others, that that they are right.

From last week’s bloody drama follows political anxiety. The massacre of this young bourgeoisie offers proof to the enemies of inclusiveness, to the enemies of openness to others, that they are right. They will say, “You apostles of this open world view, you were slain by the very ones you wanted to help. Your work has been in vain.”

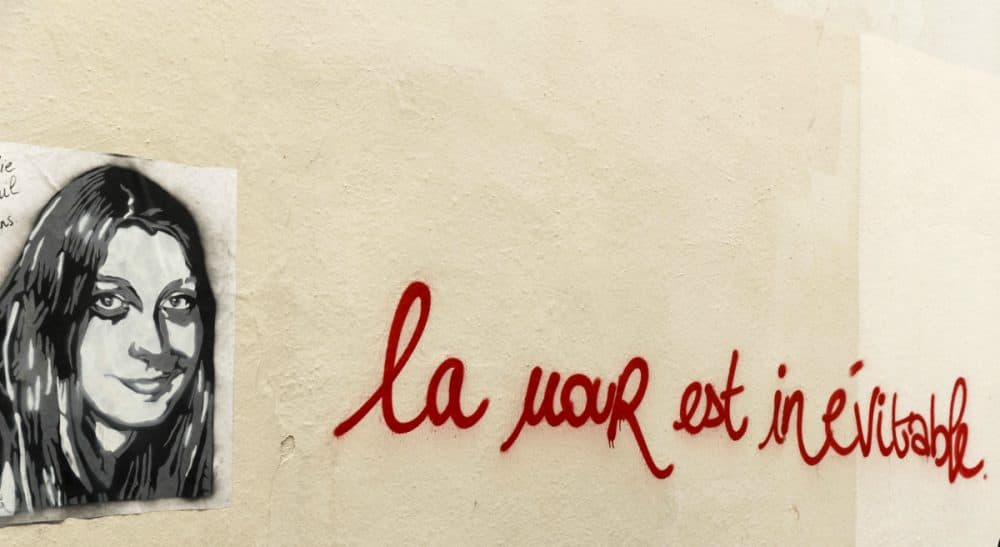

Yes, France today runs the risk of withdrawal, of closure, of isolation around an ideology of fear. No, human rights and generosity are not encoded in the genes of the French people. They are the subject of daily struggles in a country that has doubted their value for a long time now, a divided country. But we will not let Paris sink into darkness.

Paris des Lumières plongé dans le noir

par Fabien Jobard

Les Parisiens en particulier ont constaté combien les terroristes avaient démontré une maîtrise parfaite de la géographie politique et sociale de Paris.

Les attaques se sont produites en des lieux très étroits de l’espace parisien : ceux de la bourgeoisie trentenaire et quarantenaire très éduquée, ouverte au monde, qui a récemment défendu le mariage gay, par exemple, et permis le basculement à gauche, au début des années 2000, de la mairie de Paris .

La torpeur est bien plus grande que celle après Charlie Hebdo. La raison en est que celles et ceux qui parlent et écrivent (les journalistes, les écrivains, les publicistes) sont celles et ceux qui ont, très directement, été visés. Beaucoup de journalistes des rédactions parisiennes (Le Monde, Libération, Médiapart…) ont vu les événements depuis les fenêtres de chez eux.

Moi-même, j’ai vécu à 2 blocs du Bataclan, où j’ai passé beaucoup de mes soirées ; j’ai déjeuné au petit Cambodge ; les réunions de la revue dont j’étais membre, Vacarme, se déroulaient pour une bonne part rue Bichat, un des lieux de la tuerie.

Paris est une ville d’une « unsurpassed beauty », comme le disait John Tirman en se demandant « why Paris? ». C’est aussi une ville prise dans une agglomération très ségrégée. Et s’il y a une géopolitique internationale des massacres, il y a aussi une histoire sociale très vive. Tout en se jouant sur le terrain des destructions commises par la puissance américaine au Moyen-Orient et par la géopolitique du Golfe, la tuerie s’inscrit dans une lutte des classes parisienne, assise sur une polarisation territoriale très forte.

Mais s’il y a lutte des classes, pourquoi avoir choisi cette fraction de classe bien particulière? Tout simplement parce que cette bourgeoisie-là est ce que haïssent au plus haut degré les tueurs. C’est celle qui incarne et rend possible l’universalisme, le cosmopolitisme, le mélange. Une bourgeoisie qui a le souci des autres, comme ce jeune collègue, Mathieu Giroud, qui donnait des cours d’alphabétisation à des enfants sans logement, ou expulsés de logements parisiens devenus trop chers. Une bourgeoisie qui boit de l’alcool, ou du thé, avec des jeunes Arabes ou Africains, qui sont les apostats, les « kufar » des fanatiques. Comme Sarajevo lors du conflit yougoslave, cette partie-là de Paris cristallise la haine d’un monde mélangé.

Or cette fraction sociale de la population parisienne suscitait également la haine, verbale cette fois, de beaucoup de publicistes français. Ces « bobo » s’enferment dans leur ghetto de riches parisiens (il faut désormais beaucoup d’argent pour vivre à Paris), ont le souci du monde mais mettent leurs enfants dans des écoles privées, ces bourgeois narcissiques préfèrent se soucier du Népal ou des banlieues françaises plutôt que des Français, les vrais Français, les Français de nos campagnes et de nos petites villes oubliées, qui ont peu pour vivre et pour qui les « bobos » n’ont que mé pris ou oubli. Ces discours, objets des best-sellers néo-conservateurs de ces dernières années, reprennent (mais sans l’avouer bien sûr) les thèmes de la littérature réactionnaire ou fasciste des années 1930. Ces discours de culpabilisation ne visent en réalité qu’une chose : le refermement de la France sur elle-même, la fermeture des frontières, le souci d’un « soi » qui exclue tout ce qui vient du monde.

Le massacre de cette jeune bourgeoisie peut offrir la démonstration aux ennemis de l’universalisme, aux ennemis de l’ouverture à l’autre, qu’ils ont raison.

Au drame sanglant succède aujourd’hui l’inquiétude politique. Le massacre de cette jeune bourgeoisie peut offrir la démonstration aux ennemis de l’universalisme, aux ennemis de l’ouverture à l’autre, qu’ils ont raison : « vous les apôtres de la morale universaliste, vous avez été massacrés par ceux-là même que vous vouliez soutenir ; votre projet est vain ».

Oui, la France encourt aujourd’hui le risque du repli, de la clôture, de l’isolement autour d’un gouvernement de la peur. Non, les droits de l’homme et la générosité universelle ne sont pas inscrits dans les gênes du peuple français. Ils sont l’objet de luttes au quotidien, dans un pays qui doute depuis longtemps désormais, un pays divisé. Ne laissons pas Paris retourner à la nuit.