Advertisement

A Catholic Contemplates 'Spotlight'

For Catholics, “Spotlight” landed in theaters this holiday season like the proverbial coal in the Christmas stocking. Watching the recounting of The Boston Globe’s clergy pedophile investigation resurrected old feelings in this practicing Catholic. I seethed again at the men who committed these crimes and covered them up. (Full disclosure: In my past life, I was the Globe’s freelance religion columnist, and my wife until recently worked as a reporter for the paper.)

Yet the film is actually a Christmas gift. We Catholics bear special responsibility for pondering the lessons of the scandal, and special entitlement: Those were Catholic kids molested by priestly perverts. Some Catholics are drawing lessons from the movie that are obvious, even banal — appreciation for our free press and justice system, the need for “more, not less, holiness in the priesthood.” (I’m unaware of anyone calling for less holy priests.) I believe there’s a more fundamental and valuable wisdom to be gleaned from the movie. Catholics, split between theological traditionalists and liberals, must understand that, at least on this one, the liberals were right.

We Catholics bear special responsibility for pondering the lessons of the scandal...

I don’t mean that traditionalists who support church teachings on priestly celibacy, non-ordination of women, and the sinfulness of homosexuality and artificial contraception are wrong (though I believe they are). It’s more uncomfortable for the traditionalists than that: Their very premise in upholding those teachings is flawed. The premise is that, when one has doubts about a moral pronouncement by the church, the hierarchy should get the benefit of the doubt. It shouldn’t.

The premise itself rests on two observations. First, this church above all others is hierarchical, with a disciplined, military-style chain of command; obedience should be part of a Catholic’s calling. Second, the church has been in the business of philosophical and ethical reflection for two millennia, producing some of history’s most formidable minds (Paul, Augustine, Aquinas), and this should count for something. And does, for those of us who, when weighing moral questions, include the church among the references we consult.

This deference to the magisterium, the church’s teaching authority, is at the heart of the traditional Catholic outlook. Writing about the death of Edward Kennedy in 2009, Catholic author George Weigel said Kennedy personified a remaking of American Catholicism -- a regrettable transformation, Weigel implied — from one in which “the teaching authority of the Church was given the benefit of the doubt” to a “do-it-yourself Catholicism in which claims of conscience, however ill-formed, trump all.” Kennedy’s support for things like legalized abortion and contraception reflected that shift, Weigel wrote.

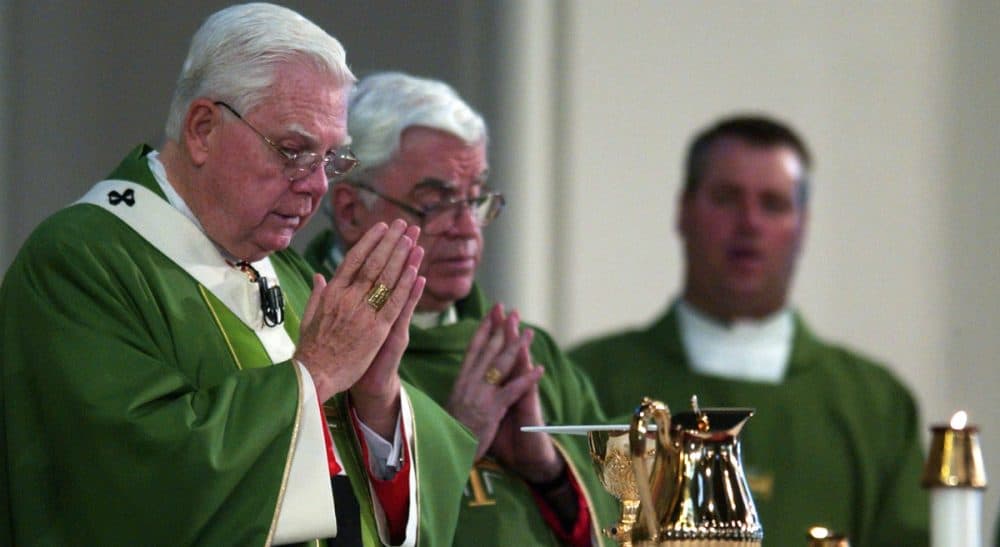

If old-school Catholics trusted the church’s teachings as the proper interpretation of God’s will, “Spotlight” reminds us that they placed similar trust in those they considered God’s representatives on earth. Priests were welcomed into devout Catholics’ homes, where, sometimes, the pedophiles among them committed their abuse. That sort of trust died with the Globe’s expose. Few mourn its passing, given that the scandal showed it was too often misplaced.

Nor should we mourn the death of deference to church teachings, which began even earlier. (Pope Paul VI released his encyclical against artificial birth control, which split the church, in 1968.) In this church with rich intellectual heritage, the intellectual case against benefit of the doubt was best made by Catholics. The Rev. Richard McCormick, a Jesuit and Notre Dame ethicist, held that the justification for such blind deference hinged on “unacknowledged and historically unsupportable triumphalism, the idea that the official teaching authority of the church is always right, never errs, is always totally adequate in its formulations.”

The premise is that, when one has doubts about a moral pronouncement by the church, the hierarchy should get the benefit of the doubt. It shouldn’t.

How unsupportable is this “triumphalism?” Enough that, occasionally, the church itself has admitted it .In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council affirmed the doctrine of "No salvation outside the church"; in 1964, the Second Vatican Council ditched it. “Vatican II overturned the doctrine by affirming the primacy of conscience — a teaching [Pope] Francis has reiterated, applying it to atheists as well,” Catholic author James Carroll wrote.

“The primacy of conscience” is what Weigel fears. And yet the church today recognizes it. My fellow Catholics would do well to remember that while watching “Spotlight,” with its implicit warning against blind faith.