Advertisement

Journalism Icon, Rookie Mistake

In 1983, 37-year-old Cecil Andrews, married, jobless and drunk, phoned an Alabama TV station one Friday night and threatened to immolate himself in the town square to protest unemployment. The station notified police and sent two cameramen to the square (to assist the cops, station management said). Only Andrews was there; officers had been unable to find him earlier and left. The crew tried to stall Andrews but then filmed for 37 seconds, as the obviously inebriated man doused himself with lighter fluid and touched a match to his leg, before trying to put out the flame.

Many journalists agreed the duo should have ditched the film-at-11 protocol and thwarted the attempted suicide. It was, to be sure, a but-for-the-grace-of-God situation; the crew was too young — one just 18 -- to have to face this ghastly tableau. But a vital principle was involved: Sometimes, obligations to humanity trump the journalist’s job.

That guilty feeling suggests [Talese] knew, at some level, that decency demanded ratting out Foos.

Obviously, watching someone spy on people having sex is less egregious than watching a man burn. And if, as a reporter, you’ve promised your voyeur that you won’t expose him, you’re obliged to honor that promise, right?

Not in this journalist’s humble opinion -- even if you are Gay Talese. The Alabama principle applies: humanity before the job.

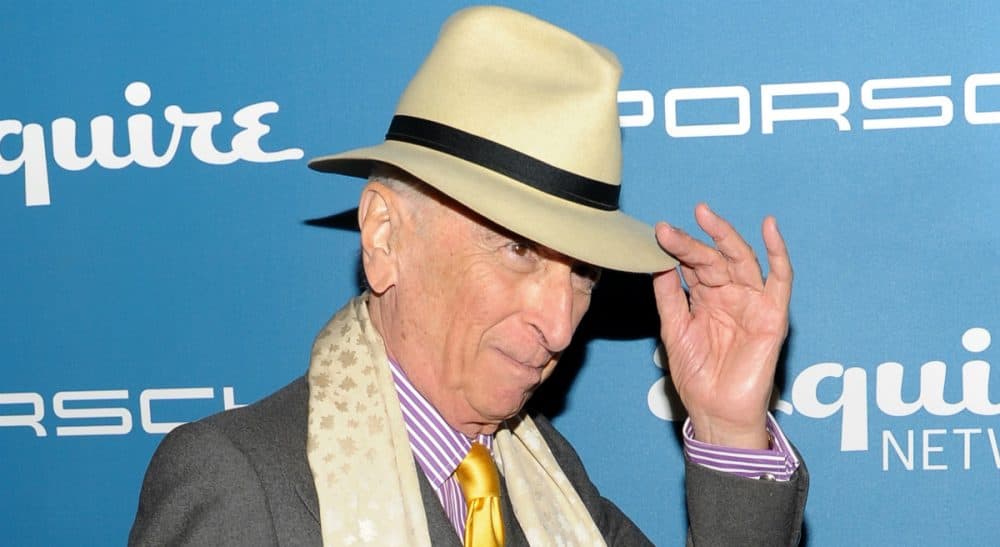

Admittedly, you’ll find journalists on both sides of this question since The New Yorker published Talese’s article, “The Voyeur’s Motel.” In it, the octogenarian author of venerated books ("The Kingdom and the Power," "Honor Thy Father") reveals that for 36 years, he’s gathered information on a Peeping Tom, Gerald Foos, who has secretly observed guests at his Denver motel during intercourse. Talese took a peep himself in 1980 to confirm Foos’s claim. The motelier made him sign a confidentiality agreement back then but released him from it three years ago.

The New Yorker’s editor defends Talese’s handling of the story, and until now, Talese kept his promise to keep quiet, even when the peeper told the writer that he’d secretly witnessed a murder in one of his rooms years before. Foos told Talese he’d reported the crime to police without revealing he’d seen it himself. Talese picks up the story:

“I spent a few sleepless nights asking myself whether I ought to turn Foos in. But I reasoned that it was too late to save the [murder victim]. Also, since I had kept the Voyeur’s secret, I felt worrisomely like a co-conspirator. I filed away his notes on the murder along with all the other material he had mailed me.”

I guess he deserves credit for admitting that fear of his own guilt helped him rationalize continued secrecy at its most morally indefensible moment. That guilty feeling suggests he knew, at some level, that decency demanded ratting out Foos. (The police found no record of the murder supposedly witnessed by Foos, who Talese says is sloppy about details and might have recorded the wrong date. Alternatively, the police report might have been lost in those pre-electronic records days. Or perhaps, some have suggested, the murder never happened.)

In Talese’s (very limited) defense, he does not idealize his subject. His article punctures the peeper’s grandiose self-conception as a serious sexuality researcher. And a confidentiality agreement is serious: Sources’ anonymity sometimes is the only way to get a vital story. But “The Voyeur’s Motel” ain’t Watergate. The only publicly valuable information here, that a snoop is illegally invading people’s privacy, is precisely the story Talese concealed for so long. I side with the journalism professor who observed, “Keeping that [confidentiality] promise allowed Foos to subject hundreds, perhaps even thousands, more guests to his voyeurism, judgment and scorn.”

Sources’ anonymity sometimes is the only way to get a vital story. But 'The Voyeur’s Motel' ain’t Watergate.

What possessed a veteran reporter to sign such an agreement in the first place? His explanation is that he didn’t take it seriously; he knew he would never write any article about Foos unless he could use his name. Yet he discovered during those sleep-deprived nights that an agreement entered too blithely had become a shackle. It and many aspects of Talese’s approach, that journalism professor said, will make future case studies of “behavior to avoid.”

A colleague suggested to me that the motel’s guests weren’t harmed, as neither Foos nor Talese ever publicly disclosed their identities. But ask yourself: If I as a reporter told you that a creep would watch you having sex, and that I might write about it -- but no worries, I won’t identify you in the story -- would you consider yourself unharmed?

It’s worth noting that in his article, Talese announced that he’s publishing a book on Foos that will have extensive entries from the journal Foos kept of his secret observations over the years. Foos received a fee from the publisher, Talese wrote. He’s not the only one in this tale who made a buck off indecent and illegal activity.