Advertisement

Resistance, Privilege, Consent, Victimizing: It's A Different Conversation Depending How Old You Are

The political tumult of the past year, particularly within the women’s movement, has revealed some surprising generational fault lines between boomer women and our Millennial or Gen Z daughters.

Was the 2017 Women’s March a righteous and inclusive show of resistance to the new Trump administration, or a narrow exercise in privilege by aging white feminists?

Was the pussy hat a rebuke to Donald Trump, or a symbol of exclusion that discriminated against transgender women?

When babe.net ran a detailed story about an unnamed woman’s upsetting sexual experiences with actor Aziz Ansari, was this a self-victimizing and misguided take-down of a generally progressive ally of the women’s movement, or a necessary exposure of hypocrisy and “normal” sexual aggression?

The answers to all of these questions seem to partially depend on the age of the person answering them. Some of these differences are the inevitable, recurring reflection of developmental stage and life experience. Others are highly specific to this cacophonous time. But here are a few threads that I’ve noticed winding through all these debates:

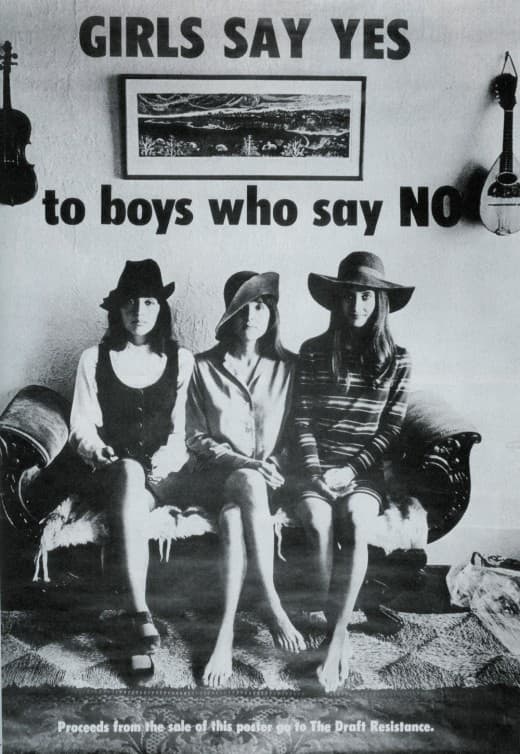

Boomer and younger women tend to have different sensibilities regarding the objectification of women. In 1968, a poster appeared in head shops across the nation. Sold to raise money for the draft resistance movement, it featured a photo of Joan Baez and her two sisters below this sly slogan: Girls say yes to boys who say no. Seen through our young women’s eyes in that quaking year, this was a page out of Lysistrata: women marshaling their sexual (withholding) power to oppose a terrible war.

Now, from the distance of many decades, most older women would see it was yet another case of women objectifying themselves in an attempt to please or control men. By the same token, I and many of my 60-something peers witnessed the parade of actors wearing black at the 2017 Golden Globe awards with some ambivalence. Sure, this symbolic statement that Time’s Up was powerful, but the fact that many of those black dresses featured cleavage-viewing, nearly breast-baring slits down the front seemed to undercut that message.

Make-up, revealing clothing — we tend to approach these traditionally “feminine” fashions with moderation. But not so for the young women I’ve spoken with. What my generation calls self-objectification, theirs calls self-expression, and feels that women should be able to dress and otherwise adorn themselves with no sexual ramifications. I’m not sure that’s possible, but I’m willing to recognize that it may be desirable.

We place different values on unity versus clarity. In-fighting — a passion to individuate on the basis of relatively small differences — is the surest way to destroy a movement. The FBI knew that, which is why they launched covert COINTELPRO programs in the 1960s and 1970s to sow doctrinal divisions within progressive organizations. We learned from that self-destructive disunity, and as a result, boomer women generally tend to have a pretty narrow view of who are enemies are these days, and a far more expansive definition of our friends. We are far more likely to forgive others who are not sufficiently conscious of their own privilege provided they are speaking out and organizing against the bad guys, or at least the even-worse guys. But our children’s generation is holding our feet to the flames, arguing that those who are quietly or ignorantly complicit with oppression are as worthy of denunciation as those who actively oppress.

We mean different things by “the personal is political.” When the second wave feminists of the late 1960s used the phrase, they meant that what we experienced as unique to us was, in fact, a manifestation of a larger social norm or political process. But, as the Aziz Ansari kerfuffle so richly illustrated, some young feminists of today see personal disclosure as a political act, as a means of outing hypocrites and moving private conversations into the public sphere where they belong.

Like practically every generation of young people before them, Millennials and Gen Z have little respect for authority. I think that’s a good thing, but suspect we differ in how we define it. Social media’s instantaneous amplification of, well, everything, seems to have bred a more general perspective that we don’t need journalists or judges, vetted content or mediated processes. We, the crowd, can decide, and our decision should generally be to accept at face value what the people on our side are saying.

I stand with Margaret Atwood in disputing that stance. When “The Handmaid’s Tale” author signed a letter criticizing the University of British Columbia’s treatment of a creative writing professor accused (and subsequently exonerated) of sexual assault she outraged #MeToo advocates by comparing the university’s actions to the Salem Witch Trials. But her point was not to say that the professor’s accusers were “hysterical little girls,” but rather that during these trials, “a person was guilty because accused, since the rules of evidence were such that you could not be found innocent.” As both Black Lives Matter and #MeToo have so painfully demonstrated, the contemporary legal process has far too often favored the powerful, not the innocent. But as Atwood warns:

“If the legal system is bypassed because it is seen as ineffectual, what will take its place? Who will be the new power brokers? … In times of extremes, extremists win. Their ideology becomes a religion, anyone who doesn't puppet their views is seen as an apostate, a heretic or a traitor, and moderates in the middle are annihilated.”

So here we are, astonished to be the old farts calling for some measure of moderation, and bearing the mixed blessing of historical perspective. Women my age are old enough to have witnessed enormous change and seasoned enough to recognize what a messy and fitful process it is. But our daughters, well, they are thankfully young and smart enough to recognize that knowing how far we’ve come must not dilute our urgency around how far we still have to go.