Advertisement

Commentary

Kids Who Read Fiction Are More Engaged, Empathetic Citizens

Nearly a third of Americans can’t name any of the three branches of government. And four in 10 Americans believe that the Constitution gives the president the power to declare war.

As a high school history and English teacher, these statistics don’t surprise me at all. Many elementary schools have reduced instructional time devoted to social studies, leaving students without rudimentary knowledge about how our government operates.

Over the past few years in my U.S. history classes, I’ve made a concerted effort to teach fundamental facts about the U.S. government, with an emphasis on the Constitution and Bill of Rights. Some policymakers have proposed that schools go even further, requiring that students pass a citizenship test before graduating.

While I would never discount the importance of possessing basic knowledge about our country’s history, improving civic literacy by no means guarantees that students will become engaged citizens.

The most powerful lessons about citizenship haven’t occurred in my history courses — they’ve happened in my English classes, during discussions about literature. Imagining life through the eyes of characters helps students understand people whose experiences differ from their own. During an era when many young people are obsessed with documenting their own lives on social media, literature encourages students to think beyond themselves.

The most powerful lessons about citizenship haven’t occurred in my history courses -- they’ve happened in my English classes.

In a recent class discussion about Margaret Atwood’s "The Handmaid’s Tale," my students engaged in a thoughtful conversation about the prevalence of misogyny in the United States today, a topic that adolescent males, especially, tend to avoid or minimize. Students reflected on the resiliency of the novel’s main character, Offred, as she attempts to survive in a totalitarian patriarchy. By immersing themselves in Offred’s narrative, students could begin to contemplate the devastating psychological pain inflicted by sexual violence.

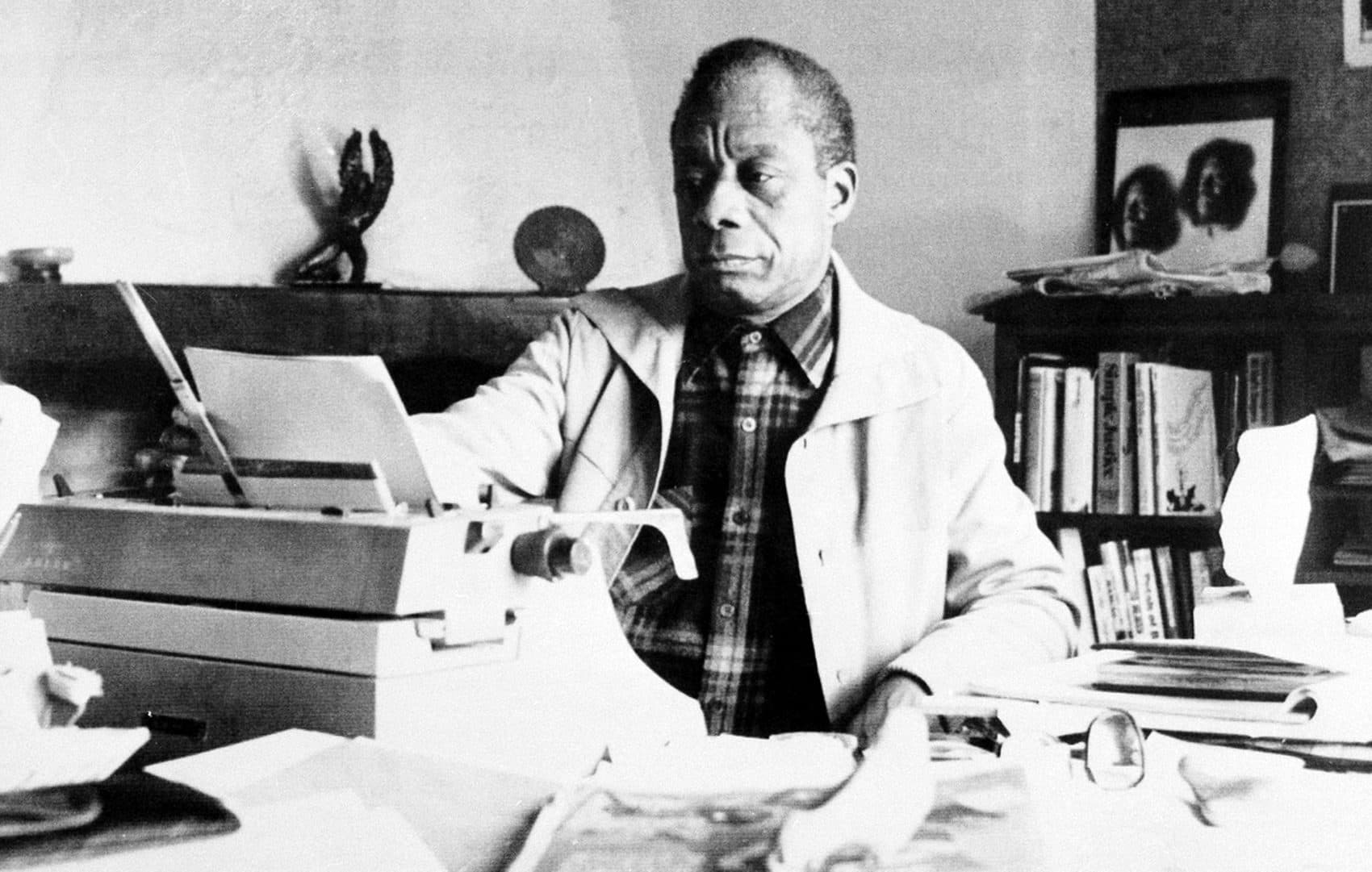

In another class, James Baldwin’s short story “Sonny’s Blues” provoked honest conversations among students about the role of race in America. Baldwin’s story chronicles the lives of two African-American brothers living in Harlem as they navigate the poverty, violence and racism of their environment. My students made connections between specific incidents in the story and current examples of structural racism. While I’m under no illusion that the story enabled white students to fully comprehend the experiences of racial minorities, I do believe that students became more cognizant of the bigotry that some of their classmates encounter on a daily basis.

By using the Atwood and Baldwin examples, I’m not suggesting that teachers should select only books with marginalized or oppressed protagonists. While it’s important that literature courses include a diverse range of voices, students benefit from imagining the world from the perspective of almost any character. My students gain a great deal of insight into human nature by reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s "The Great Gatsby," though almost every character in that novel is deeply flawed. Entering into the minds of even “unlikable” characters help students consider worldviews they don’t share, a skill that is much needed during our current era of intense political polarization.

To overcome intolerance and bigotry, students must possess the capacity for empathy and understanding that reading fiction fosters.

Research conducted over the past several years suggests that reading literature does indeed provide psychological benefits. In a widely read study, published in the journal Science, participants were asked to read texts from one of the three genres: literary fiction, genre fiction and nonfiction. The researchers discovered that only literary fiction improved participants’ abilities to understand the emotions of other individuals, suggesting that the fiction commonly taught in school courses provides unique advantages for students.

In another study, researchers at Washington and Lee University had a subset of participants read a narrative passage from a novel about a counter-stereotypical Muslim woman. The other participants read a short synopsis of the same passage without descriptive prose and dialogue. When participants later viewed a series of ambiguous-race faces, those who read the narrative passage were less likely to disproportionately categorize angry faces as Arab than those who read the synopsis. While more research needs to be done, the study suggests that fiction can change students’ assumptions about racial and ethnic groups.

Novels won’t prepare students to answer any question on the U.S. citizenship test. As the movement to reinvest in civics education gains momentum, however, let’s not forget that the ability to recite all 45 presidents, in order, won’t equip students to combat the rise in intolerance. Nor will knowledge of the Bill of Rights alone motivate students to speak out against bigotry.

To overcome intolerance and bigotry, students must possess the capacity for empathy and understanding that reading fiction fosters. Literature courses don’t teach students every fact about our government, but they do cultivate the civic virtues required to sustain our democracy.