Advertisement

Commentary

Yes, It Is 'That Bad': Why Victims' Stories Matter

In the wake of the stories of powerful men perpetuating sexual violence on women, many have wondered how we can create a climate where this behavior has no place.

At times, the accounts of behavior from men like Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer and others have seemed almost indistinguishable when repeated over news wires and radio broadcasts. Though the victims themselves are distinct individuals who all have their own stories to tell, the patterns of male behavior — ranging from inappropriate innuendo to criminal violence — are very much the same. And given the rapid pace of media sound bytes and our own societal amnesia comes the risk that we may fail to realize the full impact of rape culture’s deleterious effects on our society. But we mustn’t.

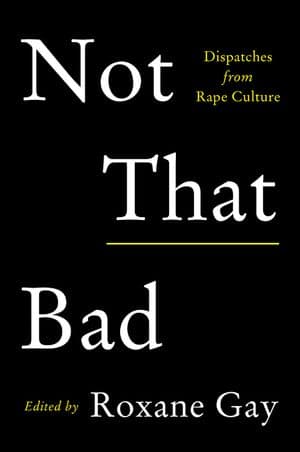

Fortunately, the 29 essays contained in Roxane Gay’s new edited collection, "Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture," ensure that we will not. The anthology offers essays from a wide range of voices; all but two are female. There are recollections of painful trauma as well as sharp observations of a world that often takes advantage of women’s’ vulnerability — even as it both rewards and punishes them for the same. This is not an easy read, but it is an important one.

In her introduction to the book, Gay opens with the story of her own horrific rape at the age of 12. Further, she notes the impulse of sexual assault victims to cast their experience as “not that bad” — partially as a coping mechanism that compartmentalizes the trauma, but also from the internalization of society’s message that victims are instead “survivors” who are “lucky to be alive” because “it could be worse.” Gay’s motivation, to first make space in the collection for people to tell their own stories in order “to share how bad this all is” is part of a larger idea — which is to grow a movement that has the potential to overwrite a culture that has long created, allowed, normalized and reinforced sexual violence and aggression.

Actress Ally Sheedy, who now teaches and mentors young actors in New York City validates the experiences of her adolescent students trying to break into an industry that sees them only as the sum of their body parts in an essay titled, “Stasis.” Through Sheedy’s own experiences (upon receiving her first big movie role, she was given a ThighMaster and told to squeeze it between her legs at least 100 times a day) and the title, itself translated from the Greek as “standing still” highlights the contiguous loop of sexism in a professional context where nothing has changed despite decades of “awareness.”

Some of the essays are matter-of-fact in their accounts, evidencing a controlled authorial restraint, though for the reader, they are heavy with sadness. xTx’s “The Ways We Are Taught to Be a Girl” shares vignettes, framed as a series of lessons, of a young girl’s stolen innocence from those in her life she should be able to trust but can’t: friends of siblings and parents, camp counsellors. The writer wonders why these violations always happen from friends or “friends of” rather than strangers, positing, “maybe because the door was already open, less work? Sitting ducks? Easy prey?” A chilling thought, but statistically accurate.

Other narratives, like Nora Salem’s “The Life Ruiner,” reveal a palimpsest of sexual transgression that follows a timeline from childhood to adulthood. Echoing Gay’s mission at the outset, Salem writes, “I’m writing this for the other girls, some of whom may be in my family…I’m writing this so it can be a part of the compendium of other sad and bad stories like these, because maybe the compendium will say something in totality that we cannot say alone.”

Before a society can change its direction, it needs to know where it is coming from. That’s why victims’ stories are an essential step on the journey. And the more they share their stories, whether from #metoo point of view or from one of advocacy, the overarching narrative will shift. There is strength in numbers, particularly when (much needed) disruption is afoot. As Leigh Gilmore writes in her 2017 book, "Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say About Their Lives," when the narrative “conforms to dominant cultural notions of legitimacy, the 'I' who narrates it will accrue authority.”

For women, that first part of Gilmore’s assessment has always been the challenge: though one in six women in the U.S. has been the victim of a sexual assault, though media continues to glamorize sexual violence, and though women around the world are publicly shamed and threatened for telling their truths, many still fear going public with their stories. Writer xTx observes, “We learn not to tell everything. We know telling everything will make them see the bad in us. How it is our fault.”

The essays contained in this volume bear testimony, but it is important to note that they are not police reports or news accounts, they are also art and should be appreciated for that as well as the truths they contain. Women have a long history of making art out of their pain, and these writers craft incisive narratives that typify poet W.B. Yeats’ notion of a “terrible beauty” — something that is at once ugly and beautiful.

While reading, I couldn’t help but think of The Odyssey’s Penelope, who, after the loss of her husband, finds her house occupied by men that are agitating for her hand in marriage — against her will. To keep the men at bay, every night she sits at her loom, weaving what she says will be a shroud for the hero Laertes. She says that she will choose a suitor once she is finished, though this is not what she wants. She mourns the loss of her husband Odysseus. Every night, she unravels her work — to protect herself, and to prevent what increasingly seems to be inevitable. Once her strategy is discovered by the suitors, she is forced to finish the work she has started. But Penelope is not forced to suffer, not this time. With perfect synchronicity, Odysseus returns home and order is restored.

Like Penelope, for years victims have been telling and then recanting their words in acts of self-preservation. Now that the moment has arrived where they must tell their stories, the timing is right. People are listening and talking back — in affirmation and validation. "Not That Bad," then, now in its fourth printing since its May release, has the potential to tip the balance in favor of those previously underrepresented and undervalued public voices. It is through this exposure that women’s own stories can — and should — become the dominant accounts of their own lived experiences.