Advertisement

Commentary

Kavanaugh’s Fate Isn’t The Only Thing At Stake

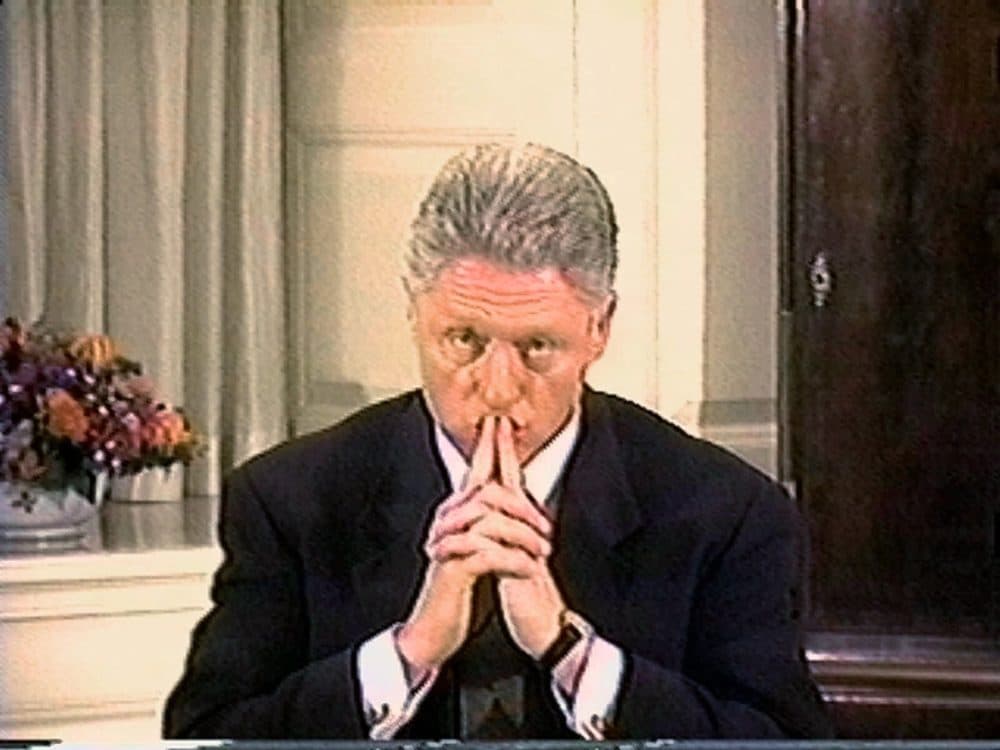

In their quest to counter Christina Blasey Ford’s allegations against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, Republicans could reach back to Bill Clinton’s striking reflections about Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas. In his testimony before the Starr grand jury in 1998, Clinton drew an analogy between the conflicting accounts Hill and Thomas gave of their workplace interactions and the contradictory answers that he and Monica Lewinsky gave when asked about the sexual nature of their relationship.

Clinton acknowledged that Lewinsky’s view of their encounters differed from his own. According to Clinton, this disparity had much in common with the divergent stories that Hill and Thomas told to the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991. He observed:

Now, in some rational way, they could not have both been telling the truth, since they had directly different accounts of a shared set of facts. Fortunately, or maybe you think unfortunately, there was no special prosecutor to try to go after one or the other of them, to take sides and try to prove one was a liar. And so, Judge Thomas was able to go on and serve on the Supreme Court.

Clinton didn’t merely say that the investigation of Hill’s charges was incomplete. Instead, he maintained that truth is unavailable when it comes to recounting sexual experience:

And when I heard both of them testify, what I believed after it was over, I believed that they both thought they were telling the truth ... This is — you're dealing with, in some ways, the most mysterious area of human life. I'm doing the best I can to give you honest answers.

Clinton was undoubtedly trying to distract Starr’s team, which, ironically, included Brett Kavanaugh. But before we dismiss his epistemology of sex as a feeble attempt to wriggle out of an embarrassing jam, we should recall that the Hill/Thomas hearings ended without any resolution. The all-male Senate Judiciary Committee concluded that no amount of evidence could prove Hill’s claims, and prevented other women from testifying to Thomas’s history of harassing female subordinates.

Likewise, in the wake of what became known as “the Lewinsky scandal” — even though the president, rather than his 21-year-old intern, was clearly to blame -- Clinton’s approval ratings soared, suggesting that his sexual exploitation of a lowly employee was, if not a cause for congratulations, then at least irrelevant to his job performance.

The current effort to ram Kavanaugh onto the Court springs from the hope that the #MeToo movement hasn’t gone far enough to prevent the inveterate tendency to disregard men’s sexual misconduct from saving the day again. When it’s he-said-she-said, history tells us, one side always wins.

These men see themselves as victims ... they believe that treating a woman’s word as if it were equal to a man’s creates a despotic imbalance of power.

In line with the Groundhog-Day quality of this controversy, Kavanaugh is currently recasting himself as the victim, just as Thomas and Clinton did, and as Trump portrays himself and others — think Roy Moore, former chief justice of Alabama's highest court and ex-White House aide Rob Porter. From the pre-#MeToo perspective of these ostensibly hapless figures, it doesn’t really matter whether their accusers are speaking the truth. These men see themselves as victims, not because they’ve been falsely targeted, but because they believe that treating a woman’s word as if it were equal to a man’s creates a despotic imbalance of power.

The assumption here is that giving women’s testimony the same credence that we extend to men’s denials exposes the accused to any charge any woman chooses to fling. From this premise, it’s a short step to surmise that if a woman lodges an allegation, she’s likely to have some irrational motive for subjecting herself to public humiliation. Perhaps, as members of the Senate Judiciary Committee claimed about Hill, she might suffer from “erotomania,” or as Bill Clinton said about Lewinski, she might be “a good girl” who “is burdened by some unfortunate conditions of her upbringing.”

If the #MeToo movement has remade the political landscape, Kavanaugh and his Republican allies may find themselves unable to explain why Ford, Deborah Ramirez and others who may soon step forward, would not only shoulder all the risks involved in speaking out, but also plead for the FBI to investigate what happened. The Republicans have so far managed to block this sensible solution, preferring to keep Kavanaugh’s defense of his honor unclouded by externally verified facts.

It remains to be seen whether the accusers’ call for impartial scrutiny will be fairly measured against Kavanaugh’s scripted performance on Fox News. But his supporters are clearly counting on his self-presentation as the beleaguered target of a politically motivated smear campaign to overcome whatever these women have to say.

The #MeToo movement emerged in direct opposition to this imbalanced dynamic, raising our hopes that women’s voices would be heard. Consequently, what’s at stake is more than Kavanaugh’s fate as a nominee.

If historical patterns hold, and he is heaved onto the Court despite deep suspicions about his character and his credibility, his presence and his opinions will push gender equality further down a seemingly endless road.