Advertisement

Commentary

The $50 I can never spend

On a recent deep clean to pass the hours stuck inside, I unearthed a bill in the back of my desk drawer. I turned to my husband, Jeff:

“Look, here’s that $50 I can’t spend!”

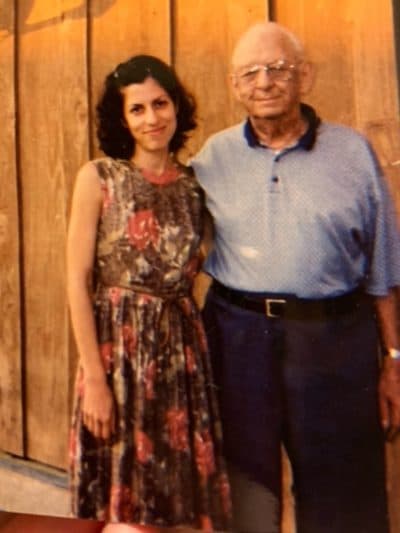

I’ve had this $50 bill since 2006. Before that, it was my maternal grandfather’s. After my mom died in a freak car accident when I was three, I spent every summer at her parents’ home in Kewanee, a small town in central Illinois. My grandfather was the chief radiologist at the local hospital. Most people knew him as Dr. Binder, my grandmother called him Paul. I called him Grumpa.

Grumpa spoiled all of his grandchildren, filling the garage refrigerator with sodas and the freezer with candy bars we could enjoy on the long, humid days of summer. But I liked to believe that Grumpa was extra sweet with me, his only granddaughter.

I accompanied him on his errands to Osco drug or to his office at the hospital, where he’d treat me to colorful Dum Dums lollipops pulled from his desk drawer. I can still remember the smell of Aqua Velva on his face when I kissed his cheek before bed, and the way he compulsively combed back his Brylcreemed hair with a black barber’s comb.

I can still remember the smell of Aqua Velva on his face when I kissed his cheek before bed ...

I was 13, sitting next to him in the den one evening before bed, when he announced that I should always carry “emergency money.”

“Emergency money is money you keep in your wallet that you never spend,” he explained. “Unless it is a real emergency.”

He handed me a crisp $10 bill, which I tucked into my purple Velcro wallet. As far as I knew, Grumpa gave emergency money to all his grandchildren, whom he lovingly called “his bees,” but I felt like the bestowal of cash was something special to me, and I took it seriously.

After the summer, back at home, I’d borrow money from my friends and take money from my dad, to spend on candy or lunch, before I would ever touch that $10 bill from Grumpa. I felt safe just knowing it was in my wallet, as though he were looking after me from miles away.

As the cost of living increased, Grumpa traded me the $10 for a $20, another bill I buried in a secret pocket of my wallet.

In college I’d call my grandmother, known as Munca, every Sunday, and after we chatted for a while, she’d say, “Let me get your grandfather on the phone.” He was brief but consistent. In a deep baritone, he would say Hi, bee before getting down to the important question:

“How are you doing financially?”

Financial security was of utmost importance to Grumpa. He grew up in depression-era Chicago, the oldest of four boys and the son of an immigrant window-washer who built his own business over decades of hard work. For Grumpa, who was quiet and sentimental, giving money to one of us — any of us, if we needed it — was a form of love. Though I didn’t think of it this way at the time.

I can’t remember when I stopped carrying emergency money. Maybe after I got my first checking account and ATM card? But I came to see through Grumpa the value of saving, of thinking not just of your future needs, but the needs of your future family. Even as a working adult, whenever I came back for visits, Grumpa would try to shove money in my pockets. My grandmother jokingly called him Daddy Warbucks.

In 2006, I was living in Brooklyn, married with my own two bees, when we got word that Grumpa had congestive heart failure. I flew to Illinois to meet him at the hospital. There I watched him, encircled by my grandmother, their two children and three grandchildren. We sat vigil and together watched as he took his last breath. That weekend, as Munca prepared to lay him to rest in the family plot in Chicago where my mother is buried, she went to look for a belt Grumpa could be buried in.

[G]iving money to one of us -- any of us, if we needed it -- was a form of love. Though I didn’t think of it as an act of love at the time.

“Ah-ha!” she exclaimed from the recesses of her closet. She’d found Grumpa’s old leather money belt. From inside the belt she pulled out six $50 bills, each folded into 12 sides.

“Here you go kids,” she laughed, distributing the bills to each of us, pocketing one for herself.

This was so like Grumpa, shoving money in our hands, even after he was gone.

And so, I still have this old $50 kicking around. It’s ridiculous. The more time passes, the less it can buy. I’ve thought about spending it on something Grumpa might like. Maybe $50 on a nice dinner. Or $50 worth of Dum Dums lollipops? I did use it once, at a movie theater in 2008. But after the movie, I immediately bought it back.

Anything I might trade for the bill would still be worth only $50 dollars; this bill is worth so much more.