Advertisement

Photos Make Chronic Pain Visible

If you live with chronic pain, you have vast quantities of company. The estimates range from a few million to one-quarter of Americans in long-lasting pain. But you might never know it. Pain is not visible. There's no 12-step group for it. And if you're hurting for long, you're likely to retreat into isolation rather than reach out to others.

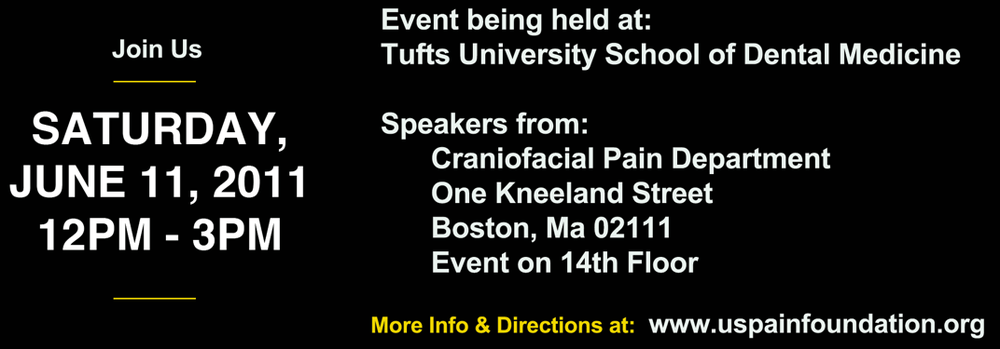

Enter the US Pain Foundation (US as of only this January; it began as the CT Pain Foundation), a volunteer-based group founded by Paul Gileno, a former chef who had to find a new calling after a broken spine left him in constant agony. It runs support groups; does advocacy work; and tomorrow, beginning at noonish, is holding a free-lunch session at the Tufts School of Dental Medicine that features The INvisible Project, which documents in photographs and text the lives of people with chronic pain. (One example is here.)

The project's aim is to educate others about the lives of people with pain, Paul said: "I think the biggest perception for people who don't have chronic pain all the time is that if they don't see it, then it's almost like they don't believe it after a while. In the beginning, if you get injured, people say, 'Are you okay?' But after a while, that chronic pain stays and it's a year later and people tend to say, 'Okay, when are you going to get better?' Well, I wish I could get better right now but my pain is still there. We're saying, 'It's real and we want you to know this is real.'"

Also, Paul said, "We want to show other people with pain that their new normal isn’t much different than everybody else's who suffers with chronic pain. We want to show them that it's okay if you're home one day and not feeling well, it's okay if this is all that you can do. We want to show them that this is the new normal and they’re not alone."

The people featured in the project have diagnoses ranging from arthritis to fibromyalgia to lupus to obscure syndromes few have heard of, but they have two things in common: They've been chosen by fate to be physically tortured, and they soldier on.

Their stories tend to be Job-like; I can't imagine what it's like to live their lives, and to tell the truth, I don't dare try. And that's part of why people with chronic pain need to connect with each other, Paul Gileno said. "You're understood on a deeper level that you need to be understood on. Because your family and friends aren't going through it and can't understand, and you need that understanding and support to move forward."

"It's so common for people to fall into such a deep state of depression and suffering," he said. "And it becomes worse because when you're depressed you move less, and your body's tightening up," worsening the pain. "You start to lose where that original pain was, because now you're riddled with pain everywhere. Our goal is to try to catch people when they're first diagnosed so we can walk them through it. Right now when people come to us" — some virtual hermits because of their pain — "it's like they can't take it anymore so they need to reach out. We want to catch people before they get to that point."

I asked Paul what the culture was like in an organization where virtually everyone suffers from chronic pain. I could imagine two possibilities: Maybe more grumpiness than in most workplaces, but also more compassion.

Over time, he said, the foundation has found many people whose pain keeps them from working but who still have valuable job skills and find volunteering very fulfilling. The key is redundancy, he said: If a project employs, say, three or four attorneys where normally one might have been enough, then "if you’re having a bad day or bad moment or bad week, you don’t feel that pressure of 'Oh my God, i have to get that work done.' We all understand that — we make sure it's not all on one person's shoulders."

Everyone understands other aspects of "the new normal" as well: "We are a little slower, our timelines are different, a lot of people are up at night so that's when they're doing a lot of work, because they can't sleep at night."

Since Paul founded it in 2006, the Pain Foundation has grown to 27,000 members, he said. There are other pain-oriented groups, including The American Pain Foundation and The American Pain Society, but he found when he was injured in 2003 that none seemed to fill his needs. "My life had changed and I started trying to meet other people whose lives changed because of pain, and I couldn't find anybody. I started the foundation just looking for other people. and it snowballed from there."

Information on tomorrow's event:

This program aired on June 10, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.