Advertisement

Scorecard Confirms Experience Of Good And Bad Elder Care

By Fran Cronin

CommonHealth intern

I thought I was doing my 86-year old father a favor last year when I moved him from New Jersey to live near me here in Massachusetts. But it turns out I may have been wrong.

According to a new report, New Jersey outperforms Massachusetts in affordability as well as in overall "long-term services and supports" for the elderly and physically disabled.

In fact, Massachusetts falls to the bottom of the heap when it comes to providing support to family caregivers. As the primary caregiver for my father, I am not surprised. Although my father lives in an assisted-living facility, his needs are more demanding than the care I give to my two children. My schedule is chock-a-block with trips to my father’s assorted doctors, making phone calls and running errands.

The report - which includes a state-by-state scorecard — was co-authored by AARP’s Public Policy Institute, The Commonwealth Fund, and California's SCAN Foundation. Its 108 pages painstakingly examine four key dimensions of LTSS — Long-Term Services and Support — performance on a state-by-state basis. They include affordability and access; choice of setting and provider; quality of life and care; and support for family caregivers.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'The question always posed with each transition –- prior to discussing need — was about my father’s Medicaid coverage.'[/module]

After much data-crunching, the Scorecard — as the report is known — confirms what many of us already know from experience: Variation in health care delivery is as broad as our nation is wide, and the gap between the top performers and the bottom-feeders is large enough to jeopardize the wellbeing of many of the 24 million adults who are over 65 or disabled.

One major systemic weakness highlighted by the report: the power of Medicaid. It states: “[Medicaid] affects the extent to which people with LTSS needs who want to avoid entering nursing homes are able to do so, by facilitating or hindering the choice of alternative settings, such as assisted living and supportive services in the home.”

In moving my father from a New Jersey hospital to a Massachusetts rehab facility and then to assisted living, the question always posed with each transition –- prior to discussing need — was about my father’s Medicaid coverage. Medicaid allowances controlled the length of my father’s hospital stay. They controlled our choice of rehab facility and length of stay. And they ensured that Medicaid would not support my father’s residence in an assisted living facility.

Dr. Juergen Bludau, director of the Center for Older Adult Health at Brigham and Women's Hospital, expressed deep frustration with the lack of coordination and efficacy of elder care services in our medically intensive Boston area.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'If we spend money more correctly, supporting people at home, we could avoid many unnecessary moves into nursing homes.'[/module]

“Taking care of elderly people, whether in a nursing home or at home, is expensive,” Bludau says. “But if we spend money more correctly, supporting people at home, we could avoid many unnecessary moves into nursing homes.”

Bludau agrees with the Scorecard, “that many nursing home residents with low care needs can be, and would prefer to be, served in the community.” Nursing home residency results in more and longer hospital stays, upping the number of confusing and debilitating transitions. These excessive transitions also correlate to poor coordination of services and poor quality of care.

My father did not move to a nursing home, but he did transition between three different care facilities until he was admitted into his assisted living facility. With each move, my father’s records were transferred along with chronic tweaking to his medication protocol and unclear notes made to his chart.

Invariably, changes would be questioned, a slew of exchanges between the two facilities would ensue; there would be another retrieval of past records, and, also invariably, a bad round of telephone tag. My father’s care remained in limbo until the cloud of confusion cleared.

More services at home = better

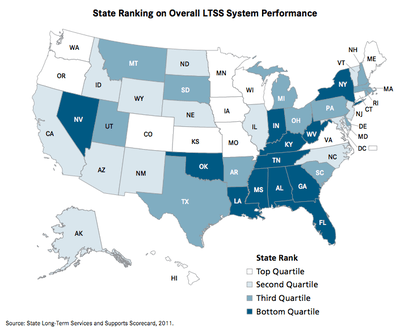

The five states scoring highest across the Scorecard’s four performance dimensions – Minnesota, Washington, Oregon, Hawaii, and Wisconsin — allocated the highest portion of their Medicaid and state revenue long-term care dollars to home-and community-based services — on average, 60% of their spending.

In the five lowest performing states – Indiana, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Alabama, and Mississippi - just 13% of Medicaid long-term care spending went to home and community. Across the nation, the average allocation was 37%.

My father left New Jersey, a state that scored an overall 22nd out of 51 (including the District of Columbia) for Massachusetts, which scored 30th. In moving, my father left behind greater access to affordable health care and a state that scored the highest in providing support to family caregivers.

He now resides in a state that does a good job providing access and choice of affordable care. But the state falls short on providing quality of life and care, and further plummets when it comes to providing support to family caregivers.

Maybe I should have moved to New Jersey instead.

For a state that has carved a first-in-the-nation niche for itself when it comes to health care, these Massachusetts failures strike a dissonant chord. In this era of health care reform, the opportunity exists to orchestrate a better system of care that strikes a best-practices balance among access, quality, and affordability.

“It would be much better to have coordinated care,” says Bludau, “especially for the older person.”

This program aired on September 14, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.