Advertisement

Will Health Reform Finally Push Doctors To Email And Skype?

No one could blame 3-year-old Anish for getting hysterical when he saw a doctor. He’d been through open-heart surgery and a skull operation. He knew that white coats often meant pain.

The first time his mother brought him to see Dr. Lester Hartman of Westwood-Mansfield Pediatric Associates, he had such a meltdown in the office that the visit had to take place in the parking lot, with the engine running, Anish in his carseat, and the pediatrician leaning his laptop on the driver’s side window as he took notes.

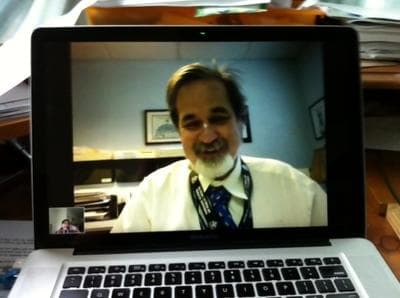

Clearly, this was not going to work. So these days, unless Anish needs to be physically seen, his parents schedule their appointments for evening hours. They sit at their home computer and they consult with Dr. Hartman, face to face, but not in person — by Skype.

Those Skype visits put Dr. Hartman way far out on the cutting edge of using technology to communicate with patients, even though Skype is now very old news in the general population. But he has high hopes that if health reform plays out as expected in Massachusetts, he'll be able to ramp up Skype and use other electronic tools more creatively in his practice. (See his guest post below.)

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]‘Why hasn’t it gone further faster?’[/module]

Health care lags dramatically — perhaps “pathetically” is the correct adverb — behind other sectors in the use of the technological tools that now tend to dominate our personal lives — email, Skype, Facebook, smartphones. As Dr. Ronald Dixon of Massachusetts General Hospital put it: “Our patients are all Skyping with their grandchildren, so why can’t they Skype with us?”

But multiplying signals suggest that early adopters like Dr. Hartman may soon get a major boost from a political source: The looming state health reform. It aims to save money by shifting care away from “fee-for-service” payments for each procedure and toward giving doctors a “global” budget for a patient’s annual care.

Health insurers do not generally reimburse doctors for time spent emailing or Skyping or texting. When a doctor is paid for each bit of in-person care, but not for such “virtual” care, that’s a major disincentive to go virtual. On the other hand, if a doctor is paid an overarching annual sum for your care and will get bonuses for keeping you healthier and within your budget, checking in with you by email or Skype may suddenly become much more attractive.

Dr. Joseph Kvedar, director of the Center for Connected Health at Partners Healthcare and a practicing dermatologist, says that under the current health-care payment system, he emails constantly with his patients for free just because he sees it as part of caring for them. But "If the cash register never rang, I wouldn't have a job. Right now, if you stop coming in to the office, I have a real problem. That won't be the case anymore two years from now. The time is upon us that it will be as quaint as bank tellers."

Signs the times are changing

Here’s one clear signal that reform could help push medicine in that direction: At a major Boston conference on technology in health care beginning Thursday, one session is billed as a debate over whether global payments are “the business model of the future” for “remote” patient care.

Here’s another signal: Dr. Neil Minkoff, medical director for the Massachusetts Association of Health Plans, says he sees three main reasons why doctors are headed toward more virtual care:

First, primary care doctors are in short supply and virtual tools could help spread a doctor farther. Second, the younger generation of doctors are digital natives. And third, "As we move from fee-for-service medicine to a global budget, physicians will have a greater incentive to use 'tele-visits' to monitor patients with chronic disease."

Long time coming

If change on this front really is around the corner, it’s been a long time coming. At a primary care conference at Harvard last week, Dr. Kvedar said: "One thing I get asked a lot when I'm out on the stump giving this vision is 'Why hasn't it gone further faster?'"

"My question is, are we ready to see this thing take off exponentially, like the curve of a hockey stick? We've been saying for 15 years that it's going to take off; what are the gating factors, and when are we going to see virtual care become part of mainstream health care?"

A tentative answer came from Dr. Ronald Dixon, director of Mass. General's Virtual Practice Pilot: "Probably now? Probably?" The expected payment reform in Massachusetts, he said, will shift doctors away from "I need to see you and I need to do something to you to get paid."

Why so slow?

Reasons abound for Dr. Kvedar's long 15 years. Reimbursement is surely high on the list, but so is concern about the privacy of patient records. So is concern about safety: Might a doctor be likelier to err on email or Skype? Add to that the concern about liability backed by an electronic trail. And the general incompatible mess of the country's electronic medical records. And the astonishing amounts of time that online communication can suck up.

Some other reasons seem to stem from the very culture of medicine: It is notoriously slow to change in many ways, even in translating solid research into clinical practice. And doctors are taught about the mystical power of "the laying on of hands," the bond that forms between doctor and patient through touch.

I suspect there's a cultural reason from the patient's point of view as well, and that is our tendency to become oddly docile and passive when we are being patients rather than people. Let me confess: I'd love to have our pediatrician's email, but I've been afraid to ask. Skype? It never even occurred to me she might.

How it could look

But that doesn't mean there's no latent patient demand for more virtual care. Consider, for example, the private Chestnut Hill plastic surgery practice of Dr. Jeffrey Spiegel, a Boston University professor of medicine.

A couple of weeks ago, I got a public-relations pitch in my In-box titled "Skype with your Doctor?"

It led me to Dr. Spiegel's office, Advanced Facial Aesthetics, where the slide show of "Before" and "After" patients on a wall-mounted television is so mesmerizing — Wow, the difference a chin can make! — that you hope to be kept waiting as long as possible. The practice is virtually all elective surgery, not covered by insurance, and Dr. Spiegel says he tries very hard to "have the kind of practice that I would want to be a patient of."

How does that translate? He estimates that he does about 10 Skype sessions a week, not actual medical consultations but more like initial assessments of potential patients, to make sure they have "sound intentions" — and for them to get a sense of whether they want him as their doctor. Some are also follow-ups.

He does not charge for Skype sessions, though they take a lot of time and his financial handlers say he should. Still, he thinks that insurance companies should in fact reimburse doctors for care via Skype.

"There's a huge disconnect, " he said. "There’s definitely a lag between technology and how patients interact with their doctors and how they want to interact with their doctors, and the way doctors are reimbursed."

As for email, Dr. Spiegel said, his patients all have his personal email, and he has staffers who spend most of the day answering patient emails. They forward to him any that need his attention, and he answers promptly. He and his staff want patients to feel "an open circuit between us and them — send pictures, stay in touch."

Of course, a private plastic surgeon's office in tony Chestnut Hill is not a model that a strapped inner-city primary care doctor can probably use. And Dr. Spiegel points out that the staffers who deal with email need space and money and benefits that a struggling doctor can't likely provide. "There's no reserve left for them to improve their quality of care," he said. "A restaurant is not going to add linens to the tables if it can't charge enough to cover those costs."

In the meanwhile

Right now, I'd describe the situation as a restaurant where a few tables have linens and many don't — in a word, patchy. I hear about doctors who do email or Skype; doctors who don't; doctors reachable only through a patient email portal; doctors who don't answer email even within the patient portal.

So what can a patient reasonably expect of a doctor, at this patchy moment in time? I asked Dr. Dixon at least week's conference. His response is below, but the bottom line is: brief, secure e-mailing, yes. Skype, too time-consuming if they're not being reimbursed — for now. Payment reform may change that.

If that prediction comes true about payment reform, it could certainly make a difference in Dr. Lester Hartman's practice. He very roughly estimates that perhaps a quarter or more of the sick children who are triaged to come in to the office could actually be helped as well or better via Skype. Not children with abdominal pain or babies under 1, of course; but Skyping could replace some visits for many of the others, including even some children with an asthma flare-up or learning disorders.

His partners at Westwood-Mansfield Pediatric Associates are already having people photograph rashes and email in the photos. [An irresistible aside: A VA doctor at the recent primary care conference reported, a bit bemused, that a patient had recently brought in an iphone photo of the previous day's stools.]

"These are things that are evolving," Dr. Hartman said. "When global fees hit, it's going to incentivize everyone to do it."

A small personal story

And in the meanwhile? Let me just share the small personal incident that launched me on this topic. As I wrote here, this summer I found a tick on my 7-year-old son and he later came down with an odd summer fever, but because he did not have a classic Lyme Disease "bullseye rash," our pediatrician declined to prescribe antibiotics. Finally, on a Sunday, I found a bullseye on his arm, and instantly phoned the doctor.

The triage nurse suggested I bring my son in on Monday. But by now I was mad. I had already brought my son in, when his fever first spiked. He'd had every indication for Lyme Disease except the bullseye, and now he had the bullseye as well. I just wanted the antibiotics. I didn't want to wait, or face the time crunch and hassle of a weekday visit. I suggested that I send an iPhone photo to the doctor on call. He agreed to take a look, warning that the resolution might not be good enough for him to tell.

By the time he was done telling me a wild story about a child whose bullseye rashes would come and go in the space of minutes, the photo had arrived in his email and he said instantly, "Yes. That's it. I'll phone you in the antibiotics."

I felt vindicated, but also a bit sheepish: I knew that by refusing to come in, I had cost the practice money, and pediatricians do not tend to live large. The practice could not bill for my email-with-iPhone, though it could have if I'd brought my son in. The doctor's willingness to do the right thing had cost him. If reform does indeed spur more health care email and Skype and assorted electronica, I'm all for that aspect of it.

I told my little tale to Joe Kvedar, and he called it a perfect example of how things could change under global payments. Ideally, he said, instead of my having to feel guilty about the doctor's unbillable time looking at my iPhone photo, I'd know that "he would be rewarded for having done that, because it's higher quality care using fewer resources."

Readers, what do you think it's reasonable to ask your doctor to do electronically? Come to WBUR's Healthcare Savvy site here to discuss.

Please stay tuned for coverage of the Connected Health conference tomorrow and Friday. If there's a session you'd particularly like to see covered, click on "Get in Touch" below and let me know. No promises but I'll try.

This program aired on October 19, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.