Advertisement

Judge In Famous 'Rosie D' Case Reflects: 'What Are People For?'

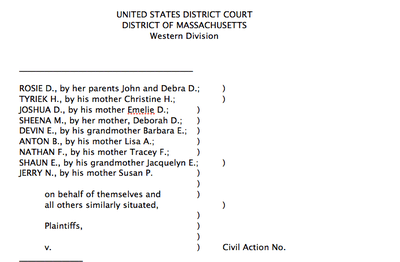

"Rosie D" is famous. A landmark Massachusetts lawsuit bears her name, a suit that continues to reverberate through the state's mental health system. "Rosie D" was the lead plaintiff in a class-action suit brought against the state, arguing that it was not doing right by its children with serious mental illness on Medicaid. Many could not get the services they needed at home, where they wanted to be.

In 2006, a federal judge, Michael A. Ponsor, ruled that yes, the state had to do better by its poor, mentally ill children. That decision has continued to play out in the years since, as the state carries out a plan to try to fix the system and offer more care to children at home. (An FAQ on 'Rosie D' is here.)

Today, Judge Ponsor spoke in Boston to the second Children's Mental Health Summit, a major meeting aimed at assessing the current state of the children’s mental health system — progress made and challenges remaining. He kindly agreed to provide the text of his remarks as prepared; nearly the full text follows. Judges don't usually get to editorialize freely from the bench; here, Judge Ponsor uses his public-podium time to pay personal homage to all the dedicated people who work in the challenging — and often under-appreciated — field of children's mental health.

A few weeks back Kate Dulit asked me for a title for these few remarks,and, on an impulse, I pinched the title from an essay by the naturalist Wendell Barry — the question “What Are People For?” I think I was drawn to the question because I wanted to try stepping back, to take a long view of the challenges faced by the people sitting in this room – advocates, clinicians, agency staff and others – and to applaud the incredibly hard, incredibly important work you do. As I tried to assemble what I was going to say, I began to fear that the title struck too grandiose a pose for my fifteen minutes of modest observations. I’ve had a tendency to make this kind of mistake in the past...

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'A solid majority of the adults who come before me in federal court as criminal defendants suffer from mental health disorders that can be easily traced to childhood.'[/module]

With that humiliating background, let me turn to my possibly over-blown question: What are people for? It seems to me that, while there may be some debate about many other justifications for human existence, one vital and obvious task we all bear, that we share with all living things, is to protect, nurture, and cherish the next generation – our own offspring as well as others’ children – and to give them the best start we can in their lives. By doing this we help to insure the continuation of our own species, and we give those who will succeed us the tools to build on what we’ve created, and, one selfishly hopes, the generosity to nurture us as we decline.

The evidence is strong that in the United States we are not doing this work very well, especially recently.

Everyone here is intimately familiar with the painful details of the situation, far more than I am, so I’ll only touch on the most prominent data. According to the Children’s Defense Fund, in 2010 16,400,000 children in the U.S., about 22 percent of all children, lived below the poverty line, defined as an annual income of $22,314 for a family of four. Of that group, 7,370,000 lived in extreme poverty, defined as an annual income of $11,570 for a family of four. Ominously, our child poverty rate is actually increasing from about 14% in the early 70's to 22% in 2010. Children under five tend to be the poorest, with roughly one in four infants, toddlers, and preschoolers living below the poverty line in 2010.

It is well established, and hardly surprising, that long-term poverty affects the mental health of children. The National Center for Children in Poverty estimates that 21 percent of low-income children have mental health problems. The same study estimates that 75-80% of children in need of mental health services never receive them. These mental health problems quickly push children, as they grow older, into my world, the justice system. I was not surprised to see that 67-70% of children in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health disorder.

I can tell you from personal experience that a solid majority of the adults who come before me in federal court as criminal defendants suffer from mental health disorders that can be easily traced to childhood and that are directly linked to the adult’s criminal behavior. In determining sentences for the defendants before me, I apply the often harsh federal sentencing guidelines.

One recognized basis for departing from these guidelines is something called “diminished capacity” – including a mental or emotional disorder that explains the criminal conduct. To insure that I could adequately assess possible diminished capacity, I began many years ago to encourage defense counsel to retain forensic psychologists to assess the background of the men and women before me for sentencing. I quickly found that a large majority of these defendants suffered clearly diagnosable, long-term mental health disabilities rooted in early childhood.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'Yours is extraordinarily hard, essential work, and it requires a patience and tenacity that borders on the superhuman.'[/module]

In this difficult environment, I am here to thank and applaud everyone here and everyone beyond these walls who has chosen to spend his or her life attempting to provide and expand mental health services for children, and particularly poor children. Whatever your position, public or private, yours is extraordinarily hard, essential work, and it requires a patience and tenacity that borders on the superhuman.

Recently I happened to encounter a historical detail that casts an ironic light on the plight of so many of our nation’s children and on the communities of professionals trying so ardently to secure needed mental health services for them. Some of you may know this historical milestone but others may not. I didn’t.

The year 2012 will mark the 800th anniversary of the so called Children’s Crusade. In 1212, as the tradition has it, 30,000 children attempted to walk to the Holy Land, believing that a divine power would cause the Mediterranean Sea to part and open a road to Jerusalem. The waters, of course, did not part, and all but a handful of the 30,000 starved, were drowned, or were betrayed by ship owners who took them on board with promises of passage and promptly sold them into slavery.

It sometimes seems to me that poor children today, especially those with mental health problems, and the people working on their behalf, face the same long odds. In some ways, the challenge is neither surprising nor complicated. Barney Frank once said something about democracy that struck me profoundly. “Democracy,” he said, “is not for the people – it is for the people who are organized.”

Children do not organize easily, as 1212 demonstrated. Children with mental health problems, and their often afflicted families, do not form effective lobbying groups. They compete for resources with vastly stronger and better equipped factions vying for a slice of the same public pie. The demands of so many deserving and needy groups place public officials in the unenviable position of having to distribute resources that seem more limited with each year. The people who advocate for children with mental health problems, as well as those who work directly for and with them within clinical settings and state agencies, must possess extraordinary patience, courage, and tenacity. Let me take a couple minutes now to describe one example: the case I it fell to me to preside over, Rosie D. v. Romney.

The lawsuit was filed on October 31, 2001, on behalf of a class of Medicaid-eligible — meaning poor — children, suffering so called “SED” or serious emotional disabilities. The lawsuit did not directly seek to establish new rights, or access new resources for children. Rather, its stated goal was to enforce a promise made in 1989 when Congress amended the Medicaid statute to declare that all children under age 21, whatever their economic status, would receive treatment deemed medically necessary by their clinicians. The plaintiffs' very able attorneys contended, in essence, that children with SED were not getting their promised services.

In response to the litigation, the defendants, also ably represented and offering entirely plausible arguments, moved to dismiss the lawsuit on purely legal grounds as an inappropriate invocation of federal judicial power. I eventually denied this motion, and in November 2002, the First Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed my ruling.

As a result, about a year after the lawsuit was filed, the real litigation began. Two and a half years later, after extensive discovery and preparation, with the attorneys on both sides working extremely hard, the case went to trial, over about six weeks, with a courtroom full of attorneys. Defendants, I am positive, resisted the lawsuit in good faith, denying any violation of the federal statutory requirements and putting on evidence that supported the Commonwealth.

It was not at all clear to me at first who should prevail. Five months after the trial and the submission of post-trial memoranda, a little over four years after the suit was filed, on January 26, 2006, I rendered my decision finding in favor of the plaintiffs. This time the defendants did not appeal.

Having found a violation of the Medicaid statute, an even harder question followed: what was the proper remedy? What should the Commonwealth do to establish a system to provide services for the class members, the Medicaid-eligible children suffering these serious emotional disabilities?

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'Serving children with mental health needs, especially poor children, is not for the faint of heart, or for people overly fond of immediate gratification'[/module]

That decision took another full year, with detailed submissions from both sides, and resulted in a comprehensive remedial order on February 22, 2007. That was nearly five years ago, and the attorneys for both sides are still regularly appearing before me, working on the implementation of the remedy, almost eleven years after the lawsuit was first filed. Most recently, this past November 22 counsel appeared before me to discuss, among other things, children’s access to Intensive Care Coordination and Crisis Stabilization Services. After more than ten years, the docket sheet currently runs 108 pages with 559 numbered entries.

Serving children with mental health needs, especially poor children, is not for the faint of heart, or for people overly fond of immediate gratification. It is a very long-term commitment. In his essay on Charles Dickens George Orwell compares the conditions of coal miners as depicted in Dickens’s novel Hard Times with the mining conditions when he was writing, in the first third of the 20th century, and he says, in one of my favorite quotes, “Progress is not an illusion; it happens, but it is slow and inevitably disappointing.” Thanks to the dedication and professional

competence of both the plaintiffs’ and defendants’ attorneys, the front-line people working with the children and agencies, the Rosie D. litigation has helped to catalyze, at least to some extent, progress in the provision of mental health services for one group of poor children.

Even with all that has been accomplished, from some perspectives, I’m sure the progress is viewed as agonizingly slow and disappointing. Nevertheless, that there is progress at all is a testament to those of you in this room who have chosen to work in this difficult arena, doing this essential work – doing the very thing that, I believe, people are for. Thanks for having me here and for listening to these thoughts, but mostly for the work you do every day. You have my respect and my gratitude. Keep at it. Don’t give up.

This program aired on December 12, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.