Advertisement

How To Outsmart The Stealthy Stomach Bug

By Aayesha Siddiqui (@aayesha)

CommonHealth Contributor

“I threw up lunch for some reason,” my friend casually texted one recent afternoon.

It didn’t stop there: Hours later, he was bolting to the bathroom. “Diarrhea…the worst!” he moaned. His experience pales in comparison to that of my coworker’s friend who, while at a swanky New Year’s Eve party, fell victim to an unexpected and violent episode of vomiting. She recounted the horror: "The floor was wood — oak, as I recall — and scattered with gorgeous area rugs...The best I could do was aim for the floor between them."

They’re not alone. Boston’s emergency departments have seen a recent increase in people with vomiting and diarrhea. The Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) counted 287 emergency department cases just in the week between Christmas and New Year's. New York is seeing a similar trend: the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reports that, over the two week holiday period in late December, there was a 50% increase in emergency department visits for vomiting and diarrhea compared to the fall months.

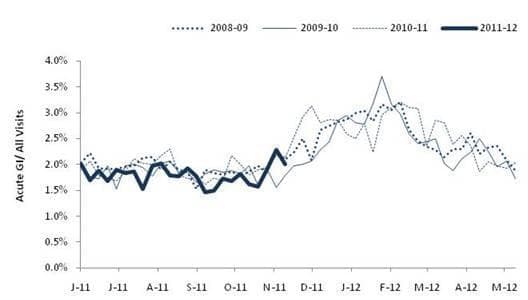

But let’s not panic just yet; this isn’t anything too out of the ordinary. Take a look at the BPHC graph below. You’ll notice that these emergency department cases of acute gastrointestinal illness (the medical name for all those trips to the bathroom) peak during the winter months:

So, what’s making so many gastrointestinal systems go haywire?

Well, there are lots of pathogens — viruses, bacteria, parasites — that could be the culprits, but there is one that stands out: norovirus. In fact, just in the last month, Minnesota, Iowa, and California have all had norovirus outbreaks.

According to the CDC, norovirus causes over 20 million cases of viral gastroenteritis every year.

About a quarter of those cases come from contact with contaminated food (often due to insufficient hand washing before preparing food). With nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the most popular symptoms, 1 in 15 Americans will be spending far more time in the bathroom than they’d like.

Virus Particle Invasion

Norovirus is spread through what’s called the oral-fecal route: Billions — yes, billions — of viral particles are present in an infected person’s fecal matter (and vomit). If an infected person doesn't wash her hands well after using the bathroom, those billions of virus particles make their way onto surfaces, counters, clothes, door handles, food, other people. If a healthy person comes in contact with these virus particles and manages to get them in her mouth (for example, by not washing her hands before she eats), then it's her turn to start running to the bathroom.

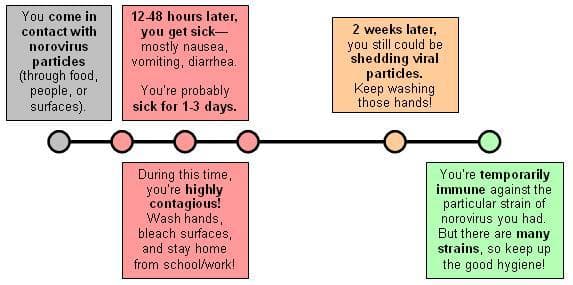

How long between sharing a meal with a sick friend and your first stomach rumbles? Here’s a timeline of how norovirus plays out:

That red box up there, the one that says you’re highly contagious — read it again. An infected person spews out billions of viral particles, but it only takes a few (as few as 20) of those particles to make a healthy person sick. This is one reason why norovirus is so easy to catch.

At The Masquerade Ball

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]Your body’s immune system is like the cadre of bodyguards stationed at the door.[/module]What makes norovirus even more of a stealthy culprit is that there are so many different strains of the virus.

Think of your body as a big masquerade ball. Your body’s immune system is like the cadre of bodyguards stationed at the door. When you get one strain of norovirus — let’s say, a wizard dressed in green — your bodyguards learn to look out for that green-clad wizard. But another strain is dressed in purple, and another is wearing a hat, and another is carrying a staff and donning a cape.

The bodyguards haven’t been instructed to look out for all these different wizards, these different strains, so they may inadvertently allow one of those wizards into the masquerade ball. Soon, that different wizard, that strain of norovirus that only slightly varies from the one you had before, is working its magic on your stomach and intestines. That’s why, if you had viral gastroenteritis due to norovirus last year, you still could be at risk of getting sick once again.

Easy Fixes

So, what should you do?

- WASH YOUR HANDS. Whether you’re sick or healthy, use soap and running water and scrub vigorously. Be sure to wash for at least 20 seconds and dry thoroughly after. (And no, hand sanitizers will not do the trick. Old school handwashing is best.)

- Disinfect surfaces. If you're sick or caring for someone sick, use a bleach-based cleaner to disinfect any contaminated surfaces, especially in the bathroom and in the kitchen.

- Keep to yourself. Stay home from school or work while you're sick. This is especially important if you work at a long-term care facility, at a school or daycare center, or in food service. (More than half of foodborne illness in the U.S. is caused by norovirus.) It's best to stay home for 2 to 3 days after your symptoms subside.

- Drink a lot of water. All that diarrhea and vomiting can lead to dehydration, with children and the elderly at the highest risk.

Epidemiology professor Wayne LaMorte of the Boston University School of Public Health reflects, “If you were to somehow quiz families who had a family member with nausea and vomiting, it would escape them to wash their hands or cleanse utensils. There’s a lack of knowledge with GI [gastrointestinal] disease.”

He goes on, “Prevention of these things is incredibly simple. The complicated part is getting people to comply with simple measures that should be taken all the time.”

Three days groaning in the bathroom, possibly infecting your whole family, vs. washing your hands and circumventing that whole mess? Simple indeed.

This program aired on January 6, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.