Advertisement

The Ultimate Lyme Disease Map — So Far

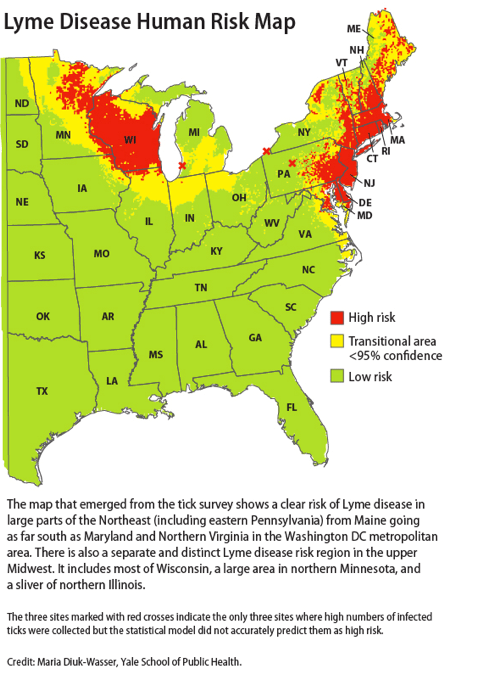

This is the ultimate Lyme Disease map for the Eastern United States — so far, that is. Those scary red blots keep swelling, and swelling, and swelling...

But at least this latest charting of the risk to humans means we're keeping better track of Lyme Disease, a tick-borne illness whose symptoms can range from a rash and fever to long-term neurological effects.

(Better track in most places, anyway. Please ignore the apparent Lyme-free zone on Cape Cod above. It's just an artifact of limits on the data.)

The map and its analysis are just out in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. I spoke today with Maria Diuk-Wasser, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health and lead author on the paper, "Human Risk of Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Agent, in Eastern United States." I pressed her to apply a superlative to the study, and she offered that this is "the largest field-based, standardized effort to describe the risk for Lyme Disease."

In concrete terms, that means that about 100 people — she eventually lost count — went "tick-dragging" all over for the ticks that carry Lyme Disease. They were trained and sent out onto a given territory with a "drag cloth," a one-meter-square swath of corduroy. They would walk along and drag the cloth behind them, and every 20 meters they would lift it up, pick up all the ticks attached to it with tweezers, preserve them in alcohol and ultimately send them in to Dr. Diuk-Wasser's team for analysis.

http://vimeo.com/35865375

It will be news to few Massachusetts residents that the state is a hotbed of Lyme Disease, and we've written about it before. But the survey further crystallizes the disease's geography, and Dr. Diuk-Wasser says that one of its findings may also help inform clinical practice: Almost everywhere that the draggers found young ticks, the usual culprits in spreading Lyme Disease, about one in five of the ticks actually carried the Lyme Disease bacterium.

That finding could simplify clinical guidelines because doctors may no longer need to consider how widespread the Lyme bacteria is among local ticks, she said. They may be able to simply make a general presumption that if there's Lyme Disease around and a tick has been on a patient at least 36 hours — long enough to transmit the bacteria — the patient's risk of Lyme Disease is about one in five.

Back to the broader geography: Why might Lyme Disease have spread in such a distinctive pattern of two huge red spots?

It's not entirely clear, Dr. Diuk-Wasser said, but it's known that in the Northeast, at the turn of the last century there was very little forest, virtually no deer, and no ticks. "Back then, it made the paper if you saw a deer," she said. The tick population and Lyme Disease had pretty much receded to a few islands. But it has been expanding outwards again since perhaps the 1920s or 1930s; "Following re-forestation, deer invaded, ticks came, and Lyme Disease followed."

Similarly in the Midwest, she said, it's believed that the deer and tick population had retreated to virtual islands — areas where they had never been exterminated — and has more recently been expanding back outward from Minnesota. The two "expansion fronts may actually merge and we may have it all through Ohio," she said.

From the study's press release:

Band of tick hunters gathered evidence for most extensive field study ever conducted. Given frequent over- and under-diagnosis of Lyme disease, map offers officials new tool for assessing risk and tracking disease spread

Deerfield, Ill. — A new map pinpoints well-defined areas of the Eastern United States where humans have the highest risk of contracting Lyme disease, one of the most rapidly emerging infectious diseases in North America, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As part of the most extensive Lyme-related field study ever undertaken, researchers found high infection risk confined mainly to the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest and low risk in the South. The results were published in the February issue of the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Given frequent over- and under-diagnosis of Lyme disease, the new map could arm the public and health officials with critical information on actual local risk.

"There has been a lot of discussion of whether Lyme disease exists outside of the Northeast and the upper Midwest, but our sampling of tick populations at hundreds of sites suggests that any diagnosis of Lyme disease in most of the South should be put in serious doubt, unless it involves someone who has traveled to an area where the disease is common," said Dr. Maria A. Diuk-Wasser, Assistant Professor at the Yale School of Public Health and the lead author of the study.

"We can't completely rule out the existence of Lyme disease in the South," she added, "but it appears highly unlikely."

The Lyme disease risk map was developed by researchers at the Yale School of Public Health in collaboration with Michigan State University, University of Illinois and University of California, Irvine, through a cooperative agreement with the CDC, which is seeking a better understanding of where Lyme disease poses a public health menace.

And:

Current geographical assessments of Lyme disease risk are heavily reliant on reports of human infections, which the study notes can be a poor predictor of risk. The researchers point out that using human cases to determine areas of risk can be misleading due to the high level of "underreporting and misdiagnosis" of Lyme disease. They also note that where someone is diagnosed with the disease is not necessarily where they contracted it.

In addition, the study found that infected I. scapularis ticks may colonize a region long before they actually infect a human with Lyme disease, which means risk can be significant even without a confirmed case.

"A better understanding of where Lyme disease is likely to be endemic is a significant factor in improving prevention, diagnosis and treatment," Diuk-Wasser said. "People need to know where to take precautions to avoid tick bites. Also, doctors may be less likely to suspect and test for Lyme disease if they are unaware a patient was in a risky area and, conversely, they may act too aggressively and prescribe unneeded and potentially dangerous treatments if they incorrectly believe their patient was exposed to the pathogen."

The study notes that "accurate and timely" diagnosis is crucial to initiating antibiotic treatments that can help patients avoid the more serious complications of Lyme disease. At the same time, the authors point out that incorrectly suspecting Lyme disease has its own consequences, including potentially life-threatening complications from the antibiotics typically used to treat infections. (While the laboratory test for Lyme disease can produce both false-positives and false-negatives, false-positives are far more likely in non-endemic areas.)

This program aired on February 1, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.