Advertisement

Commentary: How I Talk About Sex With My Kids

Guest Contributor

My thirteen-year-old daughter is now in the throes of seventh grade Sex-Ed. Yesterday, while lingering at the table after dinner, just the two of us left, she asked: “Rubbing the clitoris is what makes sex feel good, right?” I swallowed hard, hesitated for half a second, and then said “Yes. That’s a big part of it.” And the door was open for further discussion. What are the other ingredients of sex that “feels good”?

We have always talked openly about sex and the human body. I am not squeamish on these topics, perhaps in part because I am a doctor, and when my children (now ranging in age from 5-15) ask questions, I believe in answering directly and honestly.

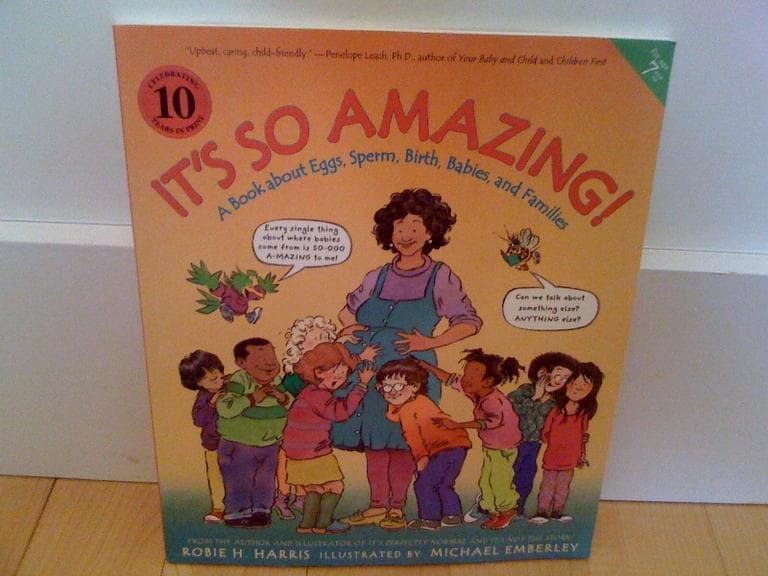

My now thirteen-year-old, a relatively uninhibited and curious child, asked about how babies are made when she was three. Her favorite book was “It’s So Amazing” by Robie Harris, and she begged me to read it to her over and over again, so I did. She asked questions, and I answered. We talked about the sperm and the egg, the penis and the vagina, and how the sperm and egg meet up (i.e., the penis goes into the vagina), and for a while, we stopped there. At some point, she discovered my diaphragm in the bathroom drawer, and, more than once, I found her using it as a frisbee. “That’s not a toy,” I would tell her. “That’s mommy’s.” For a while, that was enough, and she would obediently put it away. It was a few more years before she pressed for more details, and I told her about birth control, after explaining that grown-ups sometimes have sex even when they don’t want to make babies. Now, we have moved on to the clitoris and the concept of pleasure.

In our house, we are not shy about nakedness, or at least I’m not.

And I am not ashamed of how my body works. All of my children, at a young age, have watched me change a tampon--not a planned demonstration, but an incidental one--and have asked about what it is I am doing. Why the blood? I want my daughters, and my son, to know that menstruation is a normal, healthy part of growing up for females. “This is something that happens to teenage girls and women about once a month,” I tell them. “It doesn’t hurt, and it is a good sign that my body is working the way it is supposed to.”

Listen to your body. Love your body. Respect your body, and respect others, too. This is part of my message, and I want my children to hear it, loud and clear.

Research backs me up. A 2009 study on parent-child talks about sex and sexuality found that "more than 40% of adolescents had had intercourse before talking to their parents about safe sex, birth control or sexually transmitted diseases." Time magazine reported on the research noting:

That trend is troublesome, say experts, since teens who talk to their parents about sex are more likely to delay their first sexual encounter and to practice safe sex when they do become sexually active. And, ironically, despite their apparent dread, kids really want to learn about sex from their parents, according to study after study on the topic.

"The results didn't surprise me," says Dr. Mark Schuster, one of the authors of the new study, published in Pediatrics, and chief of general pediatrics at Children's Hospital Boston. "But there's something about having actual data that serves as a wake-up call to parents who are not talking to their kids about very important issues until later than we think would be best."

I understand the "sex talk" is tough, and I know not everyone is comfortable with my approach. When I brought home a how-babies-are-made book from the library at age five, my mother had an uncontrollable laughing fit. When my thirteen-year-old asked my husband about his own puberty last night, he was embarrassed and slightly stunned. “What was the hardest thing for you to adjust to in puberty, a) facial hair; b) your voice changing; or c) ejaculation?” she asked. Hmmm. His initial response was that none of these things were hard (unhelpful, in my daughter’s opinion). But he later came around to “facial hair” because this required a behavior change (i.e., the onset of shaving). Still wanting, my daughter told me about this discussion, and we talked more about the potential challenges of adjusting to change.

Some parents don’t believe that conversations about sex are appropriate for young children, and, understandably, they want to decide when these conversations take place. I respect this, but I am not sure silence is the answer. Sex is everywhere in our society, and kids are going to hear about it one way or another, either from friends or from the media. Isn’t it better for us, as parents, to help them make sense of what they are hearing? Frankly, I am much more comfortable talking about sperm and egg, penis and vagina with my five-year-old than I am hearing her parrot the pop song “I’m Sexy and I Know it,” after listening to the radio with her teenage sisters in the car. Disturbing images of “Toddlers in Tiaras” come to mind.

On the one hand, our prudish silence suggests to kids that sex is shameful. On the other hand, the over-sexualized media portrays sex as power. What about everything in between these extremes? What about nuance? As parents, it is our job to help kids interpret what they are hearing, and formulate new definitions. This is an opportunity. Silence isn’t going to shield our children from hearing about sex, in the same way that preaching abstinence isn’t necessarily going to stop teenagers from having sex.

According to a 2009 study in a large urban school district, 12% of 12-year-olds had had vaginal sex, 7.9% oral sex, 6.5% anal sex, and 4% all three types of sex. By age 19, 7 in 10 teenagers have had sexual intercourse. Moreover, 15-24-year-olds account for nearly half of the 19 million new Sexually Transmitted Disease infections each year. And let’s not forget teen sexual violence, and teen pregnancy. Our job is to give kids the tools they need to protect themselves and to make smart choices, and this requires dialogue. Healthy knowledge can be power.

Here’s what I want my children to know: Sex is not shameful. Sex between two mature, consenting, caring (ideally, loving) individuals can be a beautiful thing, but sex is intimate and vulnerable, emotional as well as physical, and should be respected. Sex requires maturity. Listen to your own voice. Trust yourself. Never compromise yourself.

Bottom line: we need to talk to our kids. I am not suggesting parents should give impromptu lectures on sexuality and human development. Rather, we should follow our children’s lead. They will ask the questions when they are ready for the answers.

Annie Brewster is a Boston internist and regular contributor to CommonHealth. You can read and listen to more of her work here.

This program aired on May 22, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.