Advertisement

Sick (And Poor) In Massachusetts: Longer Waits, Less Satisfied Patients

Brecah Bollinger, a 42-year-old mother of three in Quincy, requires a lot of medical treatment. But, she says, she often feels like a critical element is missing from her health care: the caring part.

Diagnosed with an immune system disorder, sarcoidosis, Bollinger has near-constant joint pain, trouble breathing, deafness in one ear and a slew of other symptoms that prevent her from holding a job, she says.

She's on MassHealth, the state's subsidized Medicaid program for low-income residents. But Bollinger says that as soon as she steps into the doctor's office, she enters a world in which she feels inferior — rushed, ignored and discounted at each step. "I call it assembly-line health care," she says. Doctors have abruptly stopped her from talking by putting a hand in her face, suggested she's addicted to painkillers and left her alone in an exam room in the middle of a medical history, seemingly too busy to take her myriad symptoms seriously, she says. Although Bollinger reports that she was assigned a primary care doctor five years ago, she's never seen her: that doctor's schedule is always full. So Bollinger says she just takes whichever provider happens to be free.

"I'm treated horribly," she says. "I want my doctor to be thorough even if it takes more than five minutes. Frankly, I'm embarrassed to be on MassHealth — they think, 'Oh, you're poor, you must be a drug addict.' Or, like, 'Your insurance doesn't pay me enough to be thorough.' "

Despite nearly universal health insurance coverage in Massachusetts, which has clearly helped residents, mainly the poor, gain access to medical care, disparities persist.

Bollinger says she has a friend with renal cell cancer who is covered by private insurance and experiences health care in an entirely different, more humane manner. "She has Blue Cross and they treat her like a queen," Bollinger says. "They pay for her transportation, and her primary care doctor, on days off, calls her just to check in."

It's tough enough being sick, but when you're sick and poor, you're far more likely to experience long waits and care that leaves you unsatisfied and feeling discriminated against because you're on Medicaid or other public insurance.

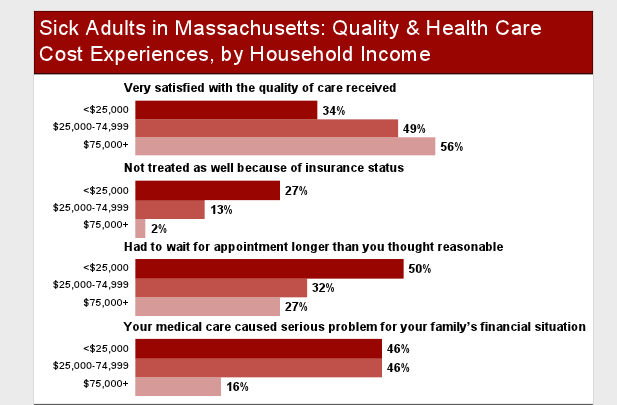

In our poll, Sick in Massachusetts, we asked residents who said they had a serious illness, medical condition, injury or disability requiring a lot of medical care, or spent at least one night in the hospital within the last year about their experiences. We found that sick people with lower incomes (under $25,000) are significantly less likely than middle-income (from $25,000 to $74,999) and higher-income folks (over $75,000) to say they are very satisfied with their care. And more than one-fourth of the lower-income sick report that they were treated worse than others because of their insurance status, a significantly higher proportion than for middle-income (13%) and higher-income (2%) sick.

Robert Blendon, of the Harvard School of Public Health conducted the poll and this morning told WBUR: "...in a world where we’re so pleased with universal coverage, beneath the surface there are still people who think they’re being treated differently based on their insurance."

A Snarky Tone And A Long Wait

"I felt I was treated like a second class citizen," said Charlene Wallace, 61, who is on Medicare (due to disability and death benefit income, she earns $4 too much to qualify for MassHealth, she says). Wallace used to visit a clinic in Lowell for her Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), chronic bronchitis, high blood pressure, arthritis, restless leg syndrome and recent heart attack, for which she takes a total of 20 medications. "When I asked why I had to get a urine test every month, the nurse raised her voice and said 'Because you have to, that's why.' You have an appointment at 11 and you're there for three hours," she said. "Even just to pick up a prescription, I'm there an hour and a half."

Indeed, according to our poll, half of the lower-income sick said they had to wait longer for an appointment than they thought reasonable, a significantly higher proportion than for middle-income (32%) and higher-income (27%) sick. The poll was conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health, the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation and WBUR.

What the poll, which surveys 500 "sick" residents of Massachusetts, shows overall is that despite widespread insurance coverage here, patients still experience serious problems related to the cost and quality of care. The poll found that about one third of sick adults report that the cost of their medical care has caused a "very serious" or "somewhat serious" financial problem for their family; and one in seven sick adults say there was a time in the past year they couldn't get the medical care they needed, either because they couldn't afford it or their insurer didn't cover it.

Collection Agency Blues

Bonnie McGhee says the quality of her care is fine, but even on Medicare, she can't pay for everything she needs. At age 67, she's got severe, "brittle" diabetes, neuropathy, acid reflux and heart problems. Medicare pays 80% of her drug costs, but she still has a hard time paying the other 20%, she said, and has already stopped taking certain medications to save money. Two years ago, she was admitted to Cape Cod Hospital six times due to extreme spikes in her blood sugar levels and other problems related to the diabetes. She still owes about $2,000 for those visits. "The collection agency keeps writing me."

To pay for her insulin, McGhee works summers as a parking lot attendant in Provincetown — 10 hours a day, four days a week. "Physically it's hard," she says. "I get very tired easily — I have neuropathy in my legs, so I don't walk right. I can do this job because I can sit in a booth."

Nancy Turnbull, an associate dean at the Harvard School of Public Health, and not involved in the poll, said she thinks the survey shows the effects of insurance coverage expansions in the state because "there are very few significant differences between lower and higher income people [when it comes to] access, financial barriers to care and almost every other measure."

But," she says, "while insurance coverage reduces disparities in care for lower income people, it doesn't eliminate them. So it's not surprising that there are still differences in the survey. Lower income people are more likely to be in limited network plans, and so have less choice of doctors and hospitals. Rising co-payments and deductibles lead people with less income to delay care, get sicker and then need appointments more urgently, appointments that might be hard to obtain in a timely way. They could be more likely to live in areas that have worse access to care than in richer areas. Poorer people encounter bias and prejudice in the health care system — against the poor, against people who have Medicaid, against people of color (who are more likely to have lower incomes). So while insurance is tremendously important, it does not equalize the health care system for lower income people."

You can view the report, Sick in Massachusetts, here and the detailed results here. And here's this morning's WBUR interview with Blendon, who conducted the poll.

The Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation, the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) and WBUR worked in partnership to produce “Sick in Massachusetts." The Foundation commissioned and funded the HSPH poll. An independent research firm, SSRS, conducted the telephone interviews and provided WBUR with the names of poll participants. WBUR met with the partners to review the poll questions and analyze the results. WBUR shared story scripts with Robert Blendon at HSPH for fact checking purposes. WBUR, using internal editing procedures, decided how to frame and expand on issues raised by the poll results.

This program aired on June 11, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.