Advertisement

Overdose Antidote: What The Government Doesn’t Do, And What You Can

You hear a lot these days about the national epidemic of painkiller overdoses. What you don’t hear so much about is what you can do to respond to those overdoses when they happen, much as we learn about CPR or defibrillators for heart attacks.

In an opinion piece just out in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Northeastern University assistant professor of law and health sciences Leo Beletsky and his co-authors argue that the government should do far more to enable the public to fight overdoses. Why doesn’t it? And what can each of us do? He explains here.

By Leo Beletsky

Guest contributor

Now a true national crisis, overdose from opioid drugs like Oxycontin and heroin kills about 16,000 Americans every year. Outranking car accidents, it is now the leading cause of accidental death in many states, including Massachusetts.

Rural and poor communities are particularly hard-hit, but contrary to popular belief, this epidemic does not discriminate: Overdose victims come from all classes, races, and age groups. Deaths afflict both legitimate and illicit users of prescription medications as well as those using street drugs like heroin.

Many of these deaths could be averted. Long-term prevention efforts are needed, but in the meantime, there are some straightforward things we can all do immediately to stop overdoses from turning fatal.

First: From the onset of the telltale signs of overdose, such as shallow breathing and slow pulse, it typically takes 30 to 90 minutes for the victim to die. This provides a precious window of opportunity to save a life. The tragic reality is that people often don't recognize the overdose in time and thus don't quickly call 911.

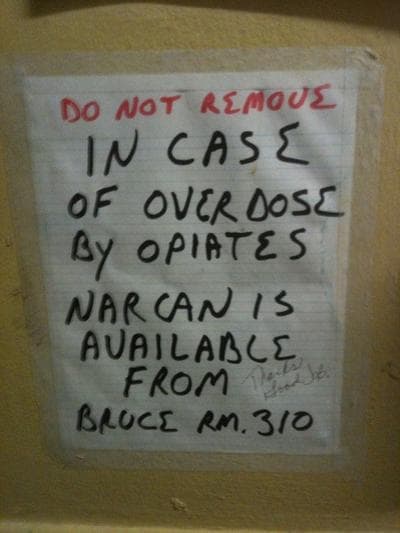

Second: Most people do not realize that once an ambulance has been called, they can help save the victim’s life. The key is to determine if the person is breathing; if not, rescue breathing and CPR should be performed. And ideally, the drug naloxone should be given to the victim.

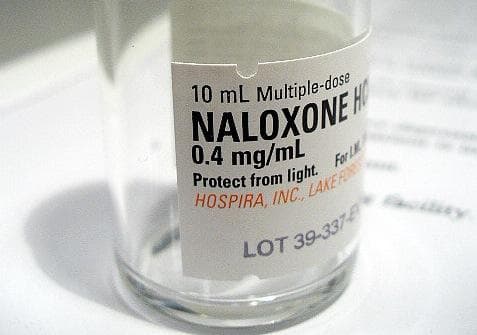

What is naloxone? Known by the brand name Narcan, it is an overdose antidote, a drug whose only effect is to reverse an overdose from opioid drugs like Oxycontin, Vicodin or heroin. Given via injection or nasal spray, it blocks the opioid receptors in the brain, typically working within about four minutes to revive the victim.

It seems like a no-brainer, doesn’t it? Shouldn’t anyone who takes opioids, or who is close to someone who does, know what to do in the event of an overdose, and keep this potentially lifesaving drug available?

In fact, however, it is much harder than it should be to get and fill a prescription for naloxone, even though it’s extremely safe and has no potential for abuse.

Why?

The central barrier is that naloxone is a prescription drug, but few doctors currently prescribe it. Some of this has to do with the fact that prescribing naloxone for those at risk of an overdose is still a new practice.

Then there is the concern that if naloxone is more widely available, people will take more risks with their drug use. Medical providers may be afraid to talk about it for fear of acknowledging overdose risk or encouraging drug abuse.

And as we have seen in other areas of public health prevention like condom distribution or syringe exchange, critics argue that making naloxone more widely available sends the wrong message.

Other barriers abound: Naloxone is in short supply, along with many other injectable drugs, and its price has skyrocketed; few licensed doctors get involved in naloxone access initiatives; and the user-unfriendly formulation approved by the FDA requires a sterile syringe. A nasal spray or pre-filled syringes are far easier to use, but are only available "off label."

Here in Massachusetts, we have an excellent model for improving overdose education and raising naloxone awareness and usage. The Department of Public Health created the Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution program. This initiative trains family and friends of opioid drug users as well as other community members to recognize overdoses, call an ambulance and use naloxone to revive the victims.

Since its launch, the program has helped save thousands of lives. Research now suggests that towns that use it widely have lower rates of overdose deaths than those without it. The state effort has also partnered with a community-based support group, “Learn to Cope,” which brings together family members and friends of drug users.

Behind the success of these programs is teaching opioid users and their caregivers how to recognize signs of opioid overdoses.

These symptoms include: Blue lips and nails, shallow breathing, pinpoint pupils, and slow or undetectable pulse. Unlike people who are merely nodding off, overdose victims do not wake up when their name is called or when shaken vigorously.

People who are at increased risk of overdose include those taking long-acting opioid medications (like Vicodin and methadone) in combination with other drugs, as well as those resuming drug use after treatment, incarceration, or other periods of abstinence.

The key is to determine if the person is breathing and to call 911. If the victim isn’t breathing, rescue breathing [CPR] should be performed. When naloxone is available, it should be administered (and re-administered if the victim does not revive within four minutes).

Increasing awareness and ensuring effective response is something that we have done with great success around cardiac arrest. Medical providers worked with patients and their caregivers to reduce risk and recognize heart attacks. Realizing that help comes too late for too many victims, public health officials have in recent years rolled out automatic external defibrillators, which are now ubiquitous in public spaces.

I doubt that anyone would place the blame on these defibrillators for encouraging poor diets, too little exercise and smoking. The same logic should apply to wider availability of naloxone.

Innovative programs like the Massachusetts model have shown that education and simple prevention measures can help curb the overdose epidemic. But Massachusetts is the only state with a comprehensive, publicly-supported program of this kind.

Nationwide, the program coverage remains dismal, with many of the hardest-hit places also lacking basic prevention infrastructure. It is time for the federal government to take on a leadership role, to take effective overdose prevention beyond the proof-of-concept phase.

Such action could include:

• A more active role for the Food and Drug Administration in ensuring adequate and affordable supplies of naloxone.

• Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services action to educate and compensate health care providers who participate in overdose education and prevention programs.

• National Institutes of Health and CDC funding for research and evaluation efforts; and coordinated agency action for boosting public awareness through multiple outreach channels.

In the meanwhile, what can people who want to be prepared for a possible overdose do?

To find an overdose education and naloxone distribution program near you, visit this program locator.

Policies and naloxone availability vary across the country, and unfortunately, many of the places with the worst overdose problems have the least prevention programs in place.

Regardless of location, however, you can ask your doctor to prescribe naloxone. That's not a practice that's widely adopted yet, but it is quickly gaining support. The recent endorsement of naloxone distribution by the American Medical Association and our article in JAMA can help encourage prescribers to talk to their patients about overdose risk, prevention and treatment. And the more people ask for naloxone, the more accepted a practice it will become.

Leo Beletsky is an assistant professor of Law and Health Sciences in the School of Law and the Bouve College of Health Sciences at Northeastern University. He is @leobeletsky on Twitter.

Further reading:

Time magazine: Preventing Overdose: Obama Administration Drug Czar Calls For Wider Access to Overdose Antidote

Time magazine: Lessons from Bon Jovi's Daughter's Overdose

This program aired on November 21, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.