Advertisement

What If Autism Risk Could be Diagnosed At Birth?

By Karen Weintraub

Guest Contributor

In what might ultimately be a game-changer for managing and treating autism, Yale researchers report that they can now identify kids at risk for autism right after birth — instead of waiting until they're diagnosed at age 3 or 4 — by examining their mother's placenta.

Harvey Kliman, M.D., a research scientist in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences at the Yale School of Medicine, says he is able to make such a determination by looking for abnormal folding in the newborn’s placenta – the organ that feeds the baby during pregnancy. Kliman's study, based on examining 217 placenta samples, is out today in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

By finding these children early, the hope is that they can begin aggressive therapy that will compensate for any behavioral, social or communications difficulties they would otherwise have had.

"Now we have something that can flag children at birth," says Kliman, a placenta expert and lead author of the study.

A Child With Faulty Folding

Chris Mann Sullivan is a believer.

Sullivan, a longtime autism behavioral therapist, sent her newborn daughter Dania’s placenta to Kliman three years ago because she thought she might recommend the analysis to her clients and wanted to try it herself.

To her shock and horror, Kliman saw evidence of this faulty folding in Dania’s placenta.

Once she recovered from her surprise, Sullivan began to try the therapies she knew so well on her own child, adapting them for Dania’s young age. Sullivan, of Norman, NC, describes her approach as intensive, “really, really good parenting.” Instead of letting tiny problems resolve themselves, she addressed them aggressively.

As a baby, when Dania, would only look and roll in one direction, Sullivan started encouraging her to use the other arm.

When the child didn’t intuitively understand facial expressions, Sullivan spent hours showing her pictures of familiar people smiling. And when Dania, who had asthma, began getting sick a lot and couldn’t seem to bounce back, Sullivan started giving her preventive nebulizer treatments every time she came in from playing outside.

Last summer, when Dania, now 3, didn’t want to stay in a wet bathing suit, her mother quickly changed it – and then regretted it when Dania’s reaction escalated into a fear of anything wet.

“You would have thought the world would have ended the first time we did not put on a dry bathing suit,” said Sullivan. But now Dania is over her aversion. “We pushed through it. Pushing through it with little kids is a lot different than pushing through with an older child.”

And that’s why it’s so important for parents to know that their child may need extra help at the very beginning of life, rather than waiting for counterproductive patterns to get established,

said Sullivan, who also switched the family’s diet to avoid additives and gluten and focus on whole foods.

Placenta As Key

Kliman discovered the association between autism and abnormal placental folds purely by accident. A placenta expert, he was often called upon to testify in court cases where parents felt they had gotten bad care during the birth of their child.

Several years ago, he was asked to examine two placentas of children diagnosed with Asperger’s on the autism spectrum. In both, he noticed subtle signs of abnormal folding; a greater degree of unusual folding had long been associated with triploidy, when a baby is born with three sets of chromosomes instead of two.

The coincidence made him wonder whether these folding problems were common in autism. A small early study suggested they were.

In the new study, he looked at 217 placenta samples, collected as part of an autism study at the University of California, Davis’ MIND Institute. The samples fell almost evenly into two basic categories, those with abnormal folds and those without. He didn’t know until later that the ones with abnormal folds were largely from the younger siblings of children with autism, while the ones without these folds were from babies without autism in their family.

“This is not a diagnosis of autism,” he said, in an interview, speaking about the significance of the abnormally folded placenta. “It's a check engine light that says something is going on.”

It’s too soon to know whether the babies whose placentas he studied will turn out to have autism. They’re still too young right now to be diagnosed.

There have never been studies of the effectiveness of behavioral therapy on children younger than about 12 months, because no one’s ever been diagnosed that young.

Lots of recent research points to the idea that “the earlier infants at risk are receiving intervention, the better the outcome,” said Daniel Coury, medical director for the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network, and a professor at Ohio State University.

“This doesn't tell us exactly what to do today, but certainly gives us ideas as we develop these early intervention techniques - we might need some earlier in life,” he said.

The fact that autism’s signature may be visible in the placenta also helps researchers understand more about the condition.

“It provides additional evidence that many cases of autism are really starting to develop well before a child is born,” said Tara Wenger, a researcher at the center for autism research at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Wenger, a toxicologist, wrote her doctoral thesis on the correlation between a child’s autism and a mother’s treatment with valproic acid for epilepsy during pregnancy. Another new study out this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association confirmed the link.

“A lot of people think of autism as something that happens after you're born – because in toddlerhood is when you start to see the signs,” she said. “But as you look at the brains, it really suggests that most of these cases are originating very early in pregnancy.”

Nailing down the timing of the autism may help lead researchers to a cause. Genes are definitely involved in setting the stage for autism, but most researchers believe that some environmental factor must also help push a child over a threshold or from high-functioning to low-functioning.

Dr. Cheryl Walker, an assistant professor of obstetrics & gynecology at the MIND Institute who helped write the new paper, said she and her colleagues are focusing on problems with the mother’s nutrition during pregnancy – including obesity, excessive weight gain, diabetes and deficiencies – as well as exposure to chemicals known to disrupt hormones.

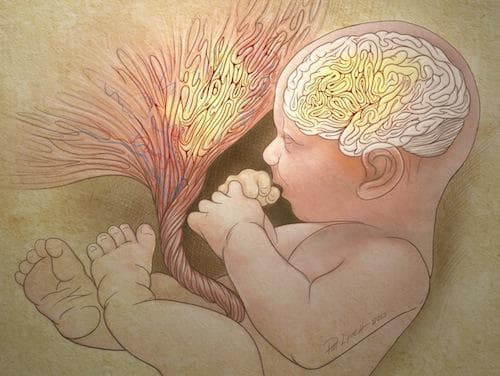

Kliman believes that autism may be characterized by abnormal folding throughout the body. Previous research has shown folding issues in tissues in the brain, gut and airways.

Looking for these abnormal placental folds is difficult and time-consuming, said Kliman, explaining that he doesn’t know of any other lab besides his own that does this type of analysis. He has not set a price on the work yet, but expects he’ll have to when word of his work reaches the public this week (and predicts the cost will be comparable to storing cord blood, which runs about $2,000). The analysis can only be done after birth, as the subtle folding changes won’t be visible with an ultrasound, he said.

Sullivan is grateful that she was able to flag her daughter’s potential problems early. There’s no way to prove that all her efforts made a difference for Dania, but she’s pretty sure they did.

Now three, Dania is healthy and ahead of her peers in language, understanding and figuring out the way the world works.

Sullivan wants to make sure that other children receive the same early treatment Dania has – and the same early warning. “When a child is 3, they've lost three years of everything, and to be able to regain that...it's very exciting both as a parent and a professional.”

Karen Weintraub, a Cambridge-based health/science journalist, co-wrote The Autism Revolution, with Dr. Martha Herbert of Massachusetts General Hospital.

This program aired on April 25, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.