Advertisement

Saving Nalini: Leading Psychologist Seeks Bone Marrow Donor To Survive

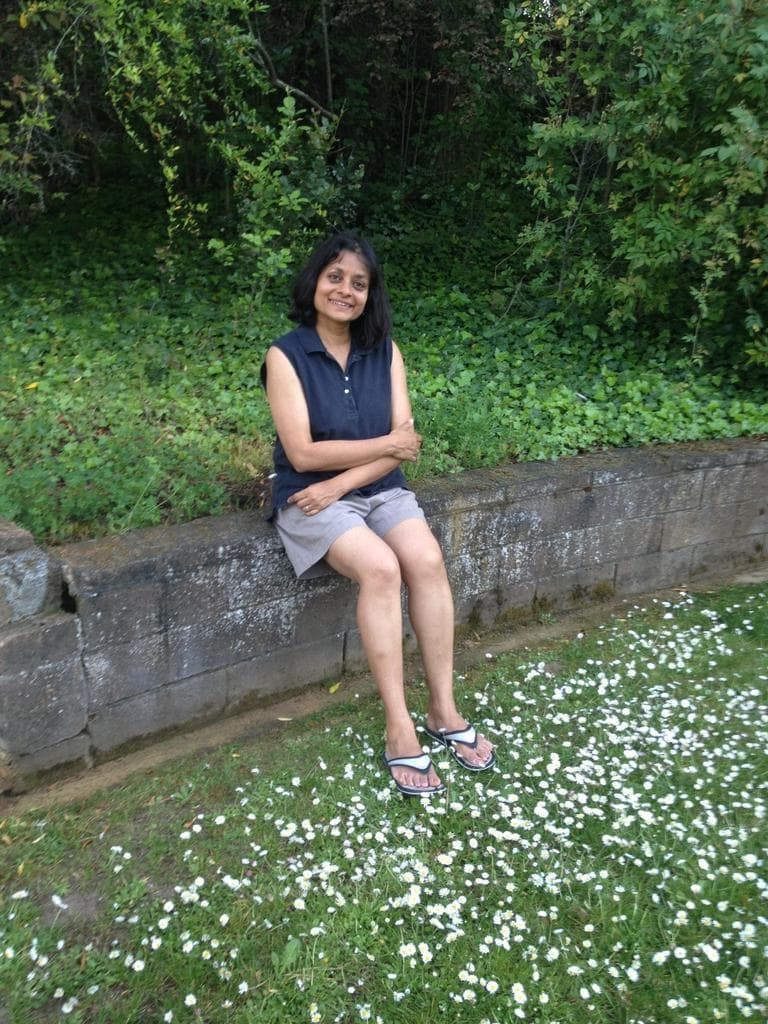

Psychology professor Nalini Ambady, formerly of Harvard and Tufts and now at Stanford, has leukemia and just weeks to live unless she finds a bone-marrow donor who matches her, most likely one of South Asian descent. Her family and friends in academia and beyond are mounting an extraordinary public effort to save her, including attempts to use the findings of her field — social psychology — to motivate potential donors. (See, for example, this Psychology Today post: Point. Click. Save This Woman's Life.) Here, Dr. Liz Gaufberg, of Harvard Medical School and Cambridge Health Alliance, shares her own plea with the public to help.

By Liz Gaufberg, MD

Guest contributor

This April vacation, my husband and our teenaged daughters decided we needed a true break. We booked a beach resort and made a pact to unplug. No cell phone. No texting. No Facebook. No Internet. No TV. We’d read books, eat meals together and talk about what matters to us. We made only one exception to the no-technology rule: Nalini.

My dear friend Nalini is in a race against time with leukemia – searching, hoping, waiting for a bone marrow donor to save her life. I am in the habit of speaking with Nalini almost every day. Everyone agreed I would be allowed to go to the hotel lobby to email her and visit her CaringBridge Site. If Nalini took a turn for the worse, I would leave our vacation early.

Day one of vacation went just as planned. Over dinner we chided each other about sunscreen and talked about the books we had cracked. Our 13 year old adored The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants. I read Nathan Englander’s book of short stories “What We Talk about When We Talk about Anne Frank.” The title story turns on a game that a contemporary suburban American Jewish couple plays. The game is a thought experiment they call “Who Will Hide Me?”

They run through a list of non-Jewish friends and acquaintances and imagine — in the event of another Holocaust — what each individual would do. Is this someone who would risk his or her own life and family to save us? Would they turn us in? After initial teen protests that the game was "morbid" and complaints about a Mom who never talks about "normal stuff," we played a few rounds at the table. What about that nice neighbor who digs our car out in the winter, would he? The bagger at Stop and Shop, would she? What would we do if someone needed us?

The game came to an abrupt end when we overhead a woman at the next table talking about our home city of Boston. Had we heard correctly? Yes. Two bombs had exploded at the Marathon. Back in our room, we quickly plugged in the TV. After bomb number one exploded, it looked at first like chaos, with people running in all directions. But as we watched, we realized...some people were actually running toward the explosion while others were running away. What would I do? Would I run in and try to help or would I clutch my children and run away? So much for our brief self-imposed ban on technology; it was the only way to find out how we might support and help, even from afar.

Our dinner table talk about saving the lives of strangers turned to saving Nalini. Nalini Ambady, a professor of Psychology at Stanford, needs to find a bone marrow donor in the next few weeks in order to survive. A match for Nalini will most likely come from someone from Nalini’s birthplace — Kerala, in Southern India. Unfortunately, the percentage of South Asians on the U.S. Bone Marrow Registry is dismally low. A South Asian like Nalini has a 1-in-20,000 chance of finding a match, while for Caucasian recipients the chance is 1 in 8.

Nalini’s friends and students have been organizing bone marrow drives on college campuses and in the South Asian community, but it has been slow going. Sitting around the table, we tried to reconcile how some people might hide a stranger in an attic or run toward a potential bomb, but others couldn’t be convinced to run a Q-tip around the insides of their mouths to potentially save the life of a kinsperson.

Being a bone marrow donor is physically easy. Screening is a simple swab of the cheek, and if you are found to be a match, donation is usually an outpatient procedure called Peripheral Blood Stem Cell collection, or PBSC. The donor receives injections for several days leading up to the donation to boost their own blood-forming cells. These new cells are then collected through an IV and filtered from the rest of the blood.

Donation is generally safe and painless – the chief barriers are psychological and cultural. There is a diversity of opinions about biological donation across cultures, with some more traditional ones considering the practice taboo. Mid-week, we were elated to learn that Nalini had a potential match — a young man from India — and then intensely frustrated when the man’s parents talked him out of donating.

No one knows better than Nalini about the social and psychological factors that mitigate helping behavior.

No one knows better than Nalini about the social and psychological factors that mitigate helping behavior. Unlike a bomb victim in your path, Nalini can remain an abstraction. Just skip that Facebook post. Don’t read this blog. But please let me keep Nalini in front of you for just a moment. Like me, Nalini is an academic and the mom of teenage girls. Her 18-year-old, Maya — my daughter Rachel’s dear friend — is a dancer who will be a freshman at Stanford next year. Her younger sister, Leena, is a ninth-grade soccer star. Once, Nalini ran to Walmart over the weekend to buy a bicycle for a needy student who was consistently coming late to class.

Nalini is — by the way — one of the top social psychology researchers in the country. Her work on “first impressions” was the basis of Malcolm Gladwell’s book "Blink." And she grows herbs outside her back door, and keeps a scissors nearby to clip them off to add to the most delectable Indian stews. If you were in her kitchen right now she’d offer you a bowl for sure.

Whenever an appeal is made to a large group of people, as Nalini’s friends are doing through social media, it’s easy to convince yourself that someone else will step up to the plate. And if you’re not Indian, you’d be right that the actual chance of your swab being ‘the one’ to save Nalini is pretty low. Swab anyway. You may end up saving someone else.

Here is a thought experiment for you. If there were someone like Nalini who needed you, would you try to help? What if it wasn’t even hard or scary or dangerous to do? I can assure you that Nalini is real and she is wonderful. She is my friend.

Will you do what you can to save her life? For donation information, and additional coverage of the efforts to save Nalini, please go to www.helpnalininow.org.

Dr. Liz Gaufberg is an associate professor of medicine and psychiatry at Harvard Medical School/Cambridge Health Alliance, and the director of the Research Institute of the Arnold P. Gold Foundation for Humanism in Medicine.

This program aired on May 3, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.