Advertisement

Please Discuss: 'Gene Drives,' Sci-Fi Scary Or Cool Leap Forward?

Perhaps you've followed that teeny tiny controversy around genetically modified foods, the "GMO" debate. Or you watched the fierce back-and-forth over whether it was a good idea to modify a strain of avian flu in the lab to make it spread more easily, in order to study it.

If this is your kind of spectator sport, it's time to learn about gene drives, a powerful new genetic technology that basically flips Charles Darwin on his head, allowing a sort of artificial selection to help chosen genes come to dominate in a population.

A paper just out in the journal eLife outlines a way to use gene drives to spread just about any altered gene through wild populations that use sex to reproduce. And a related paper just out in the journal Science calls for greater oversight and a public discourse about the potential risks and benefits of gene drive technology — now, while it's still in early stages and confined to labs.

I can already imagine the "pro" side of the debate: "This could eradicate malaria. Reduce the use of pesticides. Bolster agriculture for a crowded planet." And the "con" side: "But what if it goes wrong out in the wild? Have you read no science fiction?"

I spoke with two of the paper's co-authors: Kevin Esvelt, a technology development fellow at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and Harvard Medical School, who is also the lead author of the eLife paper; and Kenneth Oye, Professor in Engineering Systems and Political Science at MIT and director of policy and practices of the National Science Foundation's Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center. Our conversation, edited:

CG: So what exactly is a gene drive and why are we talking about it now?

Kevin Esvelt: A gene drive is a potential new technology that may let us alter the traits of wild populations but only over many generations. We think that gene drives have the potential to fix a lot of the problems that we’re currently facing, and that natural ecosystems are facing, because it allows us to alter wild populations in a way that we could never do before.

We would really like to start a public conversation about how we can develop it and use it responsibly, because we all depend on healthy ecosystems and share a responsibility to pass them on to future generations.

So how do they work? The reason we haven’t been able to alter wild populations to date is natural selection. When you say natural selection, you think, 'How many organisms survive and reproduce?' And that’s pretty much how it works. The more likely you are to survive and reproduce, then the more copies of your genes there are going to be. So genes that help an organism reproduce more often are going to be favored.

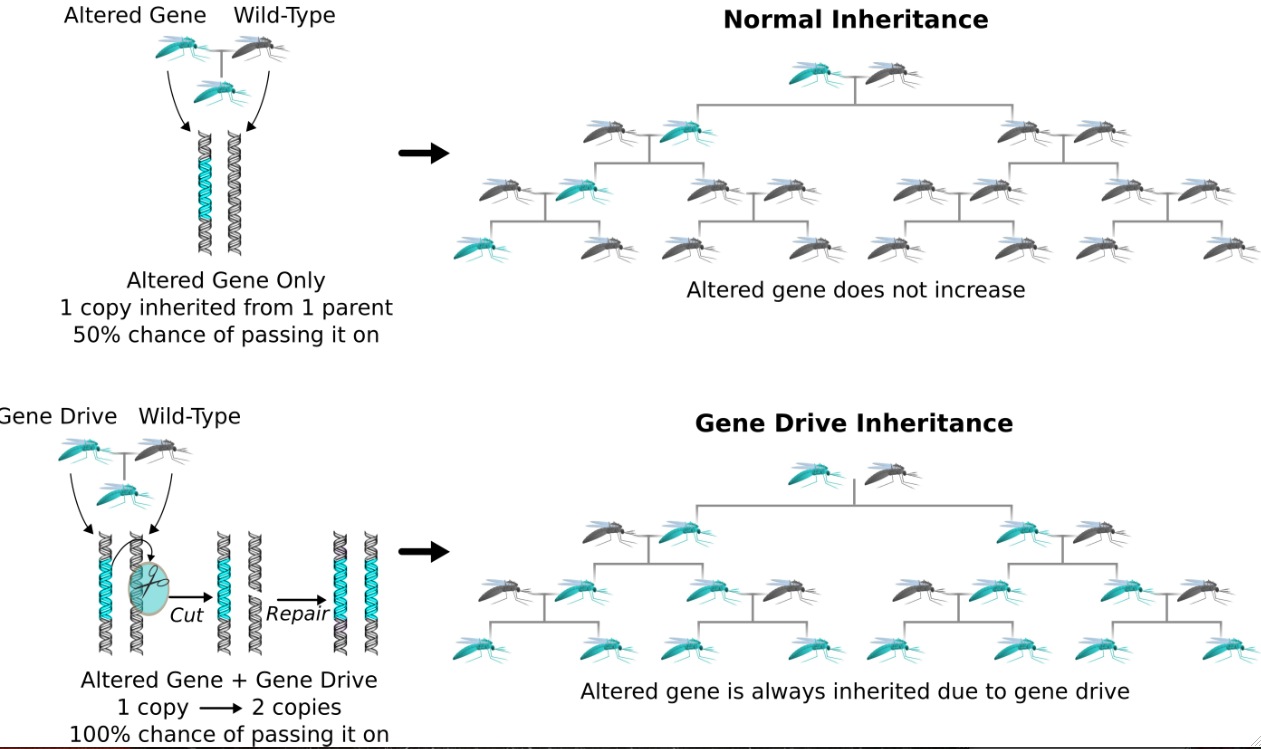

The problem is, when we want to alter a species, the way we want to alter it usually doesn’t help it survive and reproduce in nature. But that’s not the only way that a gene can reproduce. We have two copies of each gene, and when organisms have children, each of the offspring has a 50% chance of getting either copy. But you can imagine that a gene could gain an advantage if it could stack the deck — if it could ensure that it, rather than the alternate version, was inherited 70%, 80%, 90%, or 99% of the time.

There are a lot of genes in nature that do exactly this; they’ve figured out an incredible variety of ways of doing that. Almost every species in nature has what we would call an 'inheritance-biasing gene drive' somewhere in its genome, or at the very least the broken remnants of one. They’re actually all over the place in nature.

The idea that we could harness these to spread our alterations through populations has actually been around for a long time.

It was most clearly articulated more than a decade ago in amazing work by Austin Burt of Imperial College London. His idea was very simple. He said, "How about if you take a piece of DNA that cuts its competitor?'

When a gene cuts its competitor, the cell needs to fix the damage. And the best way from the cell’s perspective to fix the damage is use a template to repair it to make sure it's correct, and that’s one of the advantages of having two copies of everything. But in this case, the gene drive is the alternate copy to use as the template. So when the cell fixes the damage, it copies the gene drive onto the damaged chromosome.

Of the two chromosomes, one of them starts out with the gene drive and one of them starts out without it. The gene drive causes a break in the strand of the chromosome that doesn’t have it, and then the cell copies the gene drive over to fix the break. So you’re guaranteed to get it. You go from an organism that starts out with one copy and it goes to having two copies, and thus, when it has offspring, it’s guaranteed to contribute the gene drive to all of the offspring.

So it sounds like you’re not introducing whole new genes that are then guaranteed to be passed along. It’s that you’re changing the odds of a given gene from 50% to 100%?

The engineering side of this — and this is our contribution — is we’ve outlined a technically feasible way to do this for almost any stretch of DNA using [the gene-editing tool] CRISPR, because the way that we edit genomes with CRISPR is nearly identical to this gene drive strategy already.

What we do to edit a genome is we introduce the CRISPR system into the cell, we have it cut the gene we want to edit, and we supply an altered copy for the cell to use for repair. The only real difference here is that now we’re putting the CRISPR into the genome next to the gene we want to edit.

It still specifies that it will cut the natural version of the gene — the wild-type version. When it does that, typically just after fertilization or maybe just before the organism makes sperm or eggs, then the cell needs to fix the damage to the wild type copy so it looks for homology and it finds the altered gene and the CRISPR system, and it will just copy both of them.

So in fact you can insert a different gene if you want to?

Exactly. In theory it should let us ‘drive’ most of the traits that we know how to alter in organisms using CRISPR.

So it’s called a gene drive because it can drive the dominance of a gene?

We think of it as a drive because it uses this inheritance-biasing trick as the propulsion to launch itself through a population. We think of it as driving through a population, and it’s replicating, but the reason we use the term “drive” is because it’s the inheritance biasing that’s the propulsion — that’s the fitness advantage that ensures that it’s getting passed down to all the offspring and therefore is going to spread through the whole population.

So this has become feasible in the last, would you say, several years, couple years, or months?

Everything we’ve done with CRISPR has been done in the last two years. That entire technology has been developed from scratch in the span of two years. I want to be clear. We haven’t actually done this yet, what we’ve done is outline very clearly why we think it’s going to work because of the concept I just laid out — the mechanisms are the same.

Colleagues of Austin Burt’s have built gene drives using earlier gene-editing technologies by co-opting some of the natural genes. The problem with those is they actually don’t work and can’t work in wild organisms or for just any gene you want. But they’ve done it in artificial systems in the laboratory in multiple species.

We know the cutting and copying strategy works in the laboratory and engineered systems using cutting enzymes. We just haven’t done it specifically with CRISPR yet, and that’s partly just because we have a bad tendency to get really excited about a technology and go through and develop it without really thinking about the implications. So it gets presented to the public as a 'Hey we can do this, isn’t this great?!' And sometimes the public goes 'Whoa, we have concerns about this,' and the scientists go, 'Huh?'

And the scientists say, 'But it’s so cool!'

It’s amazing. It could address so many problems that we’re facing, and it has a tremendous number of potential benefits, but only if we make sure that it is used responsibly and really get the public involved in the decision making.

So let’s talk about potential benefits — what would the malaria scenario be?

Malaria is a really terrible disease. It kills over 650,000 people each year; most of those are children under 5. It affects over 200 million more and sickens them. When you think of a horrific public health burden, malaria is it.

With the gene drive, there are a couple different ways that we might be able to address the malaria problem that are much safer for the people and possibly for the environment as well. Malaria is spread by mosquitoes. There are a lot of different types in Africa and South Asia, which are the main areas where malaria is a problem, but only a handful of them spread malaria effectively. None of us like mosquitoes, but if they didn’t carry diseases, they wouldn’t be nearly so bad.

So why can’t we just alter the mosquito populations so they can’t carry disease? Austin Burt, who first proposed this particular form of gene drive technology, is in the mosquito field. People in that field are aware of the possibility of using a gene drive. It' acknowledged to be something of the Holy Grail application for everyone in the mosquito field.

Thats why a lot of laboratories have been working on ways to alter the mosquito so that it can’t transmit malaria anymore. They've succeeded. We now have several ways of doing that, from altering the mosquito’s immune system to changing the way it responds to the parasite, because the parasite doesn’t do anything for the mosquito either. It’s just hitching a ride. The reason the mosquito still does it is because the cost of going along is slightly lower than the cost of trying to resist. We know that making the mosquito resistant to malaria is a little costly to the mosquito, but only a little bit, and we know how to make that change.

The idea with the gene drive is okay, we have several changes that can do that — let’s start spreading them through wild mosquito populations using the gene drive. So the idea, then, is you’d still have mosquitoes, they’d be the same in every way except they would not be able to transit malaria effectively.

There are several promising ways: probably stimulating the mosquito’s innate immune system to attack the parasite more effectively is the most promising. The really nice thing about the CRISPR gene drive is that we can use it to make any of these alterations, and for the ones that require inserting new DNA we can do that anywhere in the mosquito genome. So even if the resistance gene that we insert breaks, we can release a new gene drive that inserts a fresh copy somewhere else or overwrites the previous one. So we have unlimited options for driving these genes. That’s one of the great advantages.

It’s possible this strategy won’t work because the parasite will evolve. There’s another thing the gene drives can do: they can alter some of the genes that are important for reproduction in the target organism. These are ideas that Austin Burt originally outlined. And we could potentially use those ideas to suppress the population of mosquitoes to a low enough level that they wouldn’t be able to effectively transmit malaria in an area. And then once the malaria is eradicated because there aren't enough mosquitoes in high enough densities to carry it, then we can stop and let the mosquitoes come back.

I can just imagine Charles Darwin turning over in his grave...

I think he would love it. Darwin was amazingly prescient. This whole idea of altering traits in the wild — Darwin said, 'Man selects only for his own good, nature only for the being which she tends.” Natural selection naturally selects for traits that help the organism survive and reproduce, to make the organism better at its job of living. While we breed bulldogs that require birth by C-section to survive, their heads are that large.

The really nice thing is that gene drives can be applied to any disease that’s carried by an insect vector — so malaria, dengue, yellow fever, Lyme, sleeping sickness, the list goes on. And most of those are mosquitoes — not necessarily the same species of mosquitoes.

A couple other potential benefits: A lot of our agriculture depends on herbicides. There are a lot of advances focused on no-till agriculture, which is a lot easier on the topsoil because you have less erosion and keep more nutrients in the soil. But to do that you do need herbicide, and our best herbicide — glyphosate — generally works great, the problem is that a lot of weeds are evolving resistance.

With current technology we can’t do anything about that. We have to develop another herbicide and use that instead. But with a gene drive, we could roll back that mutation to the ancestral version where the weed is still sensitive. We don’t have to alter the crop, we’re just restoring it back to what it was.

Still, wouldn't this make the GMO opponents protest vehemently?

It’s not a GMO food issue because it’s not in the crop. Essentially, we’re making our chemicals work better, and this applies to organic foods too, which use natural pesticides. The insects and weeds have been evolving resistance to those, too. So this could help organic farmers, too. We don’t have to develop and introduce new chemicals that the weeds don’t have resistance to yet; we can keep using the ones that are tested and maybe even develop chemicals that are totally inert to everything and then gene-drive vulnerability to those chemicals specifically in species. We could potentially have much, much safer pesticides and herbicides. That would require much more research but it’s a great possibility.

We have to emphasize that the gene drive is just the motor that spreads the alteration through the population. The effects are going to depend on what the alteration is and what species we’re spreading it through. So it really doesn’t make sense at all to say, 'Should we use gene drives?' because that could mean anything. Rather, we should ask, 'Is it a good idea to consider driving this particular change though this particular population?'

We're going to need to ask that question over and over again for each of the possible applications I described, and then whatever else people come up with. So we’ll have to engage over and over again, and each case is going to be unique because the ecosystem that we might be affecting is unique.

But couldn't people be so scared of something getting loose into our natural populations and being unstoppable because of the power of the gene drive that they say, 'We’ll put a blanket moratorium on using this technology?'

You certainly could, and if it was everyone in the world, I would agree with that. But I would say we actually have no business whatsoever telling people in Africa who suffer from malaria whether they should use a gene drive. We’re not going to be affected by any of those consequences. Those mosquitoes don’t exist here and any ecosystem ripple effects won't affect us. We’re not affected by malaria; they are. We’re not going to be affected by the side effects if something happens, they are. That means it’s their decision, not ours.

Ken Oye, how would you sum up the challenge and what do you propose?

The first issue is: to what extent can we do a preliminary assessment of the implications for environment and for security? The article we did does a bit of that - we try to work through how gene drives might affect target species and what environmental side effects might emerge. And we examined potential security issues associated with the development of gene drives — uses against humans, against crops, against livestock.

Our preliminary take is that although everyone always says 'Oh. My. God. People are going to be using gene drives to target ethnic subgroups or modify humans,' we don't think that's viable. Gene drives work over generations, and humans take a long time to reproduce. And with medical sequencing coming in, gene drives would likely be detectable in human populations. So it just isn’t likely to be a big deal as a direct threat to humans.

Let's flip to animals and crops. You’re talking about shorter reproductive cycles. Much of American agriculture is done with seed produced on seed farms, and much of our livestock is produced with artificial insemination. The artificiality of the way we do our food production, ironically, provides protection against the potential misuse of gene drives. Seed farms can be monitored. Artificial insemination contains or limits the mating choices of animals.

And at the same time — and we want to underscore that this is potential — there might be potential for misuse against farmers who do not rely on industrial methods of agricultural and livestock production — subsistence farmers, people growing plants in developing countries, or American farmers who do not use typical methods of relying on commercial agriculture. So we are drawing attention to a possibility we think should be analyzed and better understood.

If you look at environmental consequences — this is where we put a lot of our work in that Science article — the potential environmental effects and side effects are extremely complex. Kevin made the point that if you're evaluating gene drives you have to look at the specific species and the alteration, but I would also highlight context — the ecosystem within which the gene drive is released.

One of our co-authors on this piece is Jim Collins, an evolutionary ecologist and also former head of the biological division of the National Science Foundation. Jim and other evolutionary ecologists bring to the table an understanding of the complexity of natural systems, and that understanding is essential to the evaluation and management of potential ecological implications and effects.

The recommendations we offered in the article were the product of what can only be described as a complex multidisciplinary process. We had in the room synthetic biologists and evolutionary biotech firms and environmental organizations, government regulators and research funders. People actually agreed on important issues. What they agreed on were areas of potential environmental effects; the areas of uncertainty over those effects; the need for publicly funded research to better understand environmental implications, and even the specification of a research agenda to improve our understanding of effects.

Of course, there were disagreements on longstanding controversies such as application of the precautionary principle. But the good news is there was consensus on key areas of uncertainty, the priority areas of research and the need for public funding. The fact that the NSF was sitting in the room and had funded the meeting to discuss research agendas was also encouraging.

It’s quite unusual for a technologist to step forward with a technology at an early stage and invite public discussion. This is quite a novel technology. To have the discussion before rather than after the release, to have broader engagement by larger communities of scientists and publics is something to be commended. Not all scientists would do it.

Readers, thoughts? For further reading:

The New York Times: A Call To Fight Malaria One Mosquito At A Time

The Boston Globe: Harvard Scientists Want Gene Manipulation Debate