Advertisement

'Cowboy' Doctors Could Be A Half-A-Trillion-Dollar American Problem

When Dartmouth economics professor Jonathan Skinner was speaking recently at the University of Texas about the "cowboy doctor" problem, an audience member objected: "You have a problem with cowboys?"

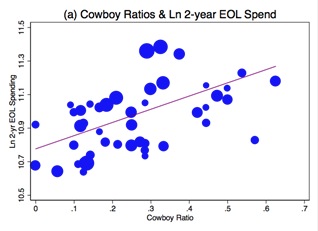

Well, actually, we all have a problem with cowboys — when they're doctors. Including the Texans. New research written up in a National Bureau of Economic Research paper finds that "cowboy" doctors — who deviate from professional guidelines, often providing more aggressive care than is recommended — are responsible for a surprisingly big portion of America's skyrocketing health costs. The paper concludes that "36 percent of end-of-life spending, and 17 percent of U.S. health care spending, are associated with physician beliefs unsupported by clinical evidence."

Whoa, Nelly. That means cowboy doctors are a half-a-trillion-dollar problem. But mightn't they also be good? Wouldn't many of us want a go-for-broke maverick when we're in dire medical straits? I asked Prof. Skinner, who's also a researcher at the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, to elaborate. Our conversation, lightly edited:

So how would you define a cowboy doctor?

Cowboys go it alone. They have developed their own rules and they don’t necessarily adapt those rules to what the clinical evidence would suggest. So if you actually talked to what we term a 'cowboy doctor,' he or she would say, 'I get good results with this procedure for this type of patient.’ That’s why we found it so interesting: they go beyond what the professional guidelines recommend. And it’s not as if they were out there before the professional guidelines got there. Sometimes pioneers are doing things that the guidelines haven’t figured out yet. But we found no suggestion that subsequent guidelines were consistent with what these physicians were actually doing.

So is it stubbornness, then?

I don’t know if it's stubbornness but it’s individuality. It's the individual craftsman versus the member of a team. And you could say, 'Well, but these are the pioneers.' But they're less likely to be board-certified; there's no evidence that what they're doing is leading to better outcomes. So we conclude that this is a characteristic of a profession that's torn between the artisan, the single Marcus Welby who knows everything, versus the idea of doctors who adapt to clinical evidence and who may drop procedures that have been shown not to be effective.

Yes, the extent of the variation in medical practice is striking. But I was most struck in your paper by how big a piece of the health-cost problem this could be. Can you quantify that?

We were surprised, too. What we show is that the opinions of these physicians — in particular, opinions that are outside of the clinical guidelines — explain as much as 17 percent of total variation in health care spending, which is, roughly speaking, 3 percent of GDP.

Wow. What is that in billions?

The association we found suggests it's almost half a trillion dollars.

Can you give me a concrete example of how a cowboy doctor could drive up costs?

What we chose to look at was a very common problem and a very expensive disease, particularly among the elderly: congestive heart failure. Our approach was to develop vignettes that characterized typical patients that a doctor might see. For example, an 85-year-old male with severe congestive heart failure who appears in the doctor's office. We provide detailed clinical characteristics about that patient, and then say to the doctor: 'Here are maybe six or seven different options. Which ones would you choose?' And they could check all of them, they could check none of them, it was really up to them.

For example?

One example was that they could basically just make the patient feel better. They could send him home with increased oxygen. They could perhaps talk about the possibility of palliative care. These are patients who are very much at risk of dying over the coming year. Or they could send them to the hospital to try to get some of their fluids under control. But the alternatives were very much more aggressive. They were treatments where there’s either no evidence of any improvement or there’s actually some evidence that these treatments could harm the patient. They will certainly lead to this poor 85-year-old man spending a lot of time in a hospital bed with very uncertain benefits.

What might those more aggressive treatments be?

For example, admitting the patient to the Intensive Care Unit. The doctor is told that the patient is uncomfortable but if you increase his oxygen he's comfortable and he feels better. One of the aggressive options is to admit this patient to an ICU, where it’s not clear what the benefits are for that patient but it is clear that admitting the patient would lead to a substantial increase in Medicare billing.

What might guidelines-based care cost compared to cowboy care in this case?

We can look at percentages: What we find is that cowboy doctors were associated with nearly 60 percent greater spending among patients near the end of life.

OK but....As patients, or family members of patients, don't we all feel like we want cowboy doctors? The kind who pull all the stops and go for the long shots even if hope is dim?

That’s a great question, but I would actually prefer not to have a cowboy doctor. Simply because, if I'm 85 years old, and I'm at high risk of dying anyway, I would want to be comfortable. I do not want to go to an ICU. And in fact, hospitals have all kinds of exotic diseases that can very badly affect frail elderly people. There are real downsides.

There seems to be a real shift toward less aggressive end-of-life care, but what about all the rest of us? Aside from the fact that we’re contributing to the high health costs in this country, what would you say to the run-of-the-mill patient about the downsides of having a cowboy doctor?

I would be uncomfortable about doctors who are basing their decisions on their own intuition rather than on clinical studies, randomized trials. And the reason is that, for example, a surgeon might say, 'I get good results with this procedure.' And he or she probably does, but the problem is that the surgeon never sees what happens to the patients who don’t get the procedure. And so they have really no basis for comparison except for kind of an intuition or a sense that, 'Well, after I did the surgery, my patient improved.'

A personal case: I had back problems and I went to my back surgeon. Here at Dartmouth, it just happens that the surgeons are very conservative — and he said something like, 'I don't want to be the one to put a knife in your back without my being convinced that this will improve your outcome.' And as it turned out, I got better anyway, which happens a lot. But if they do operate on you, they never know that you might get better anyway.

I know people’s intuitions aren’t always good. You know, men think they can pick stocks better than women and they end up doing worse. We know that. I don’t want my medical decisions to be left to someone’s intuition.

This goes beyond the scope of the paper, but how does this translate into useful information for medical consumers?

The Internet should be used with caution because there is so much misinformation, but there is also quite a bit of valuable information, particularly from trusted medical sources like the National Institutes of Health. So if the doctor is telling you, 'I think we should do this procedure' and you go online and find a study that says the patients who are like you didn't seem to improve with that procedure, I think you should at least print out the study and bring it to the doctor and say, 'What’s up?'

Or ask the doctor, 'What's your evidence?'

Exactly. Or go see a different doctor.

You found that cowboy doctors are a bit more likely to be older guys, but not by much. You also found that cowboys are likelier to be in solo practice, right?

Yes, that was a strong result, that people in solo practice are more likely to be cowboys. Group or staff-model HMOs or hospital-based practices, and board-certified cardiologists, tend to be more conservative.

The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has been doing this work for years, finding striking regional differences in medical care and spending. How much does it look like the cowboy thing explains of all that?

What we find is that by just going into a region and asking a handful of doctors about how they would treat a hypothetical 85-year-old male with congestive heart failure — how often they would have the patient come back for visits — measures like that explain over 60 percent of the variation in regional spending across the United States. We were very surprised.

So how does that happen? Why are there so many more cowboys in one place than another?

That is a great question. I think cowboys maybe like to practice together, they hire one another. But that's something we've been looking at quite a bit. We're working on it.