Advertisement

Why The Primary Care Problem (Lower Status, Pay) Matters

Guest Contributor

Medscape just published its annual physician compensation survey. The survey includes almost 20,000 physicians and is given online, so it’s probably not entirely representative.

Also, the survey results are self-reported, and physicians generally under-report their income. But the comparative reported income among specialties is informative. This survey is among the largest available, and does not require an expensive paid subscription.

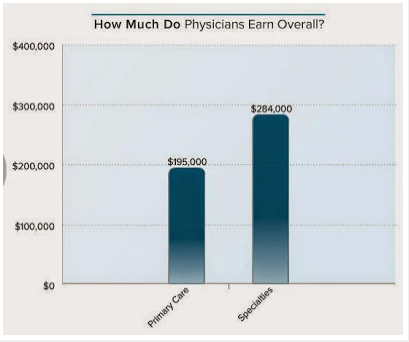

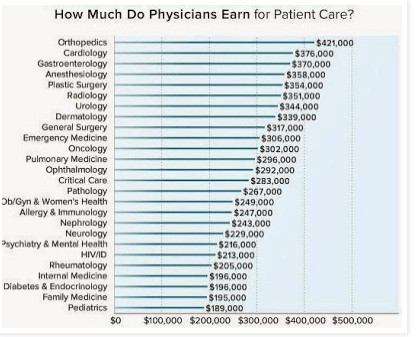

The results are no surprise. But they're worth noting: Specialists make 45 percent more than primary care physicians, and orthopedists make 224 percent more than pediatricians.

The majority of respondent physicians were employed, and men consistently make more than women in the same specialty. Women have the largest representation in specialties with the lowest incomes.

Physician income was a bit lower in the Northeast but higher in the Northwest. Massachusetts’ physicians report that their income is 46th in the nation.

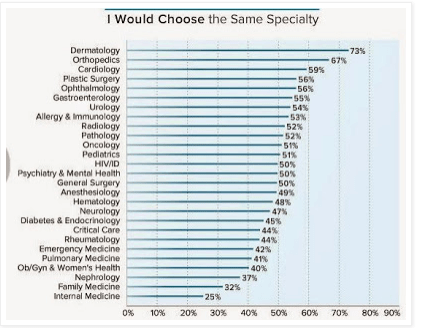

Internists are the least satisfied in their job (47 percent), and the least likely to choose their specialty if they could choose again (25 percent), but high in the rankings of specialties where the respondent would choose medicine again (71 percent).

Family physicians were only slightly more likely to choose the same specialty again as internists (31 percent), yet they were the most likely to say they would choose to go into medicine again (74 percent).

Pediatrician income is among the lowest of all specialties, yet they are twice as likely to say that they would choose the same specialty. Internists and family physicians would go into medicine again, but they would go into sub-specialties, and not do general primary care. The high cost of health care in the U.S. is in part due not to a shortage of primary care physicians, but also due to a surplus of specialists.

Why does all this matter?

The American College of Physicians reported on the impending "collapse" of primary care in 2006. There have been efforts to change this situation since, including "patient centered medical homes," and short-term enhanced Medicaid primary care fee schedules built into the Affordable Care Act.

The continued relatively lower pay of primary care physicians and the lack of job satisfaction of general internists and family physicians means that our historic way of delivering primary care is about to change. Much future primary care is likely to be delivered by nurse practitioners or physician assistants, and some office-based primary care will be supplanted by telehealth or by apps with underlying algorithms.

The Medscape survey suggests that we will continue to face serious challenges to continue to deliver the highly personalized primary care which many of us value, and the highly coordinated care needed by the frail elderly and those with serious chronic illnesses.

The problem is about money, of course, but also about perception: The average pediatrician in this survey was paid $189,000 per year, the lowest amount of any of the surveyed specialties. Still, this is in the top 6 percent of all earners in the U.S.

The primary care perception of being underpaid is related to the high earnings of specialists, and this will only change if there are large decreases in specialist income.

Modest increases in primary care income just won’t change this perception, and huge increases in primary care income would be hard to afford.

Recent efforts to train more physicians are not likely to lead to more practicing primary care physicians unless we are more successful at improving the lifestyle and status of those who practice primary care. We’ll just likely have more specialists, and our costs of health care will continue to be the highest in the world.

Jeff Levin-Scherz, MD, MBA is an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Public Health. He blogs at Managing Healthcare Costs, where an earlier version of this piece was published.