Advertisement

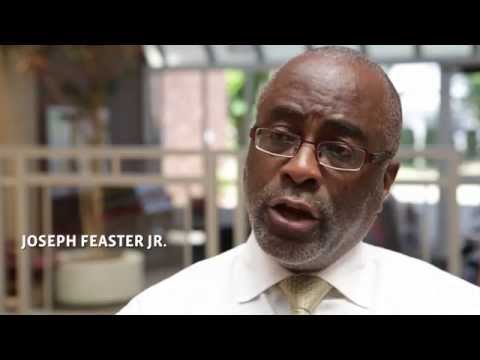

'I Don't See Any Stigma': Father Fights Suicide In Black Community After Son's Death

Resume

Joseph Feaster Jr. is not a minister. He's a successful Boston attorney. But for the last five years he's been doing a lot of preaching about a subject close to his heart.

"My ministry right now, because it's even more personal — it involves my son — is around mental health," Feaster says. "And if I can help the next person to understand it, to get through it, that's my being."

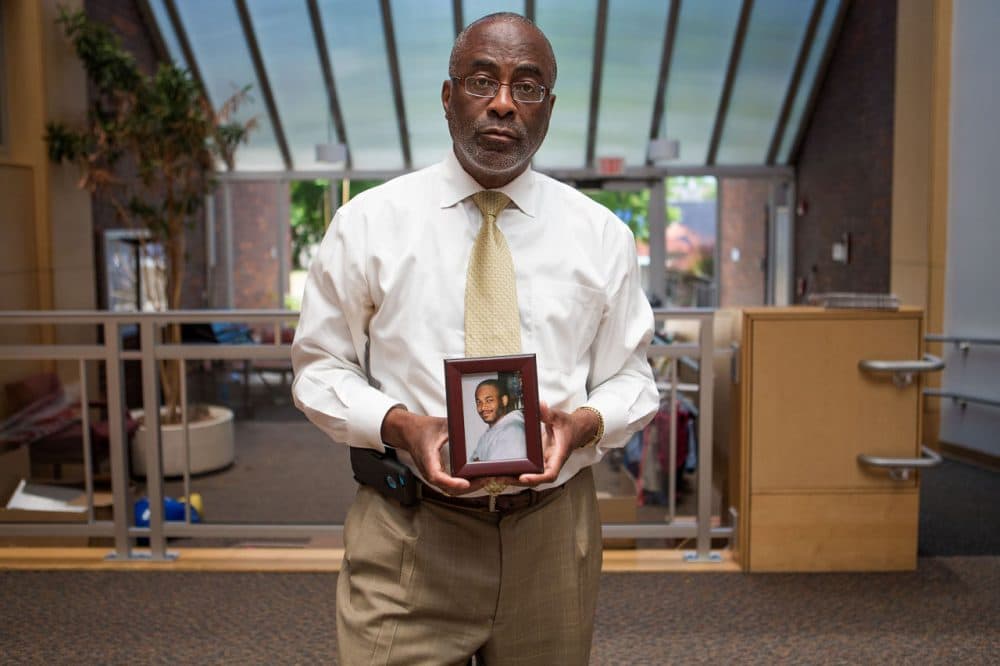

His son carried his name and was thereby Joseph Feaster III. He died by suicide in 2010, at the age of 27.

His death came at a triple-decker on Elmore Street in Roxbury, not far from Dudley Square. That's where he had lived most of his life — first with his parents and sister, and then renting an apartment from his father.

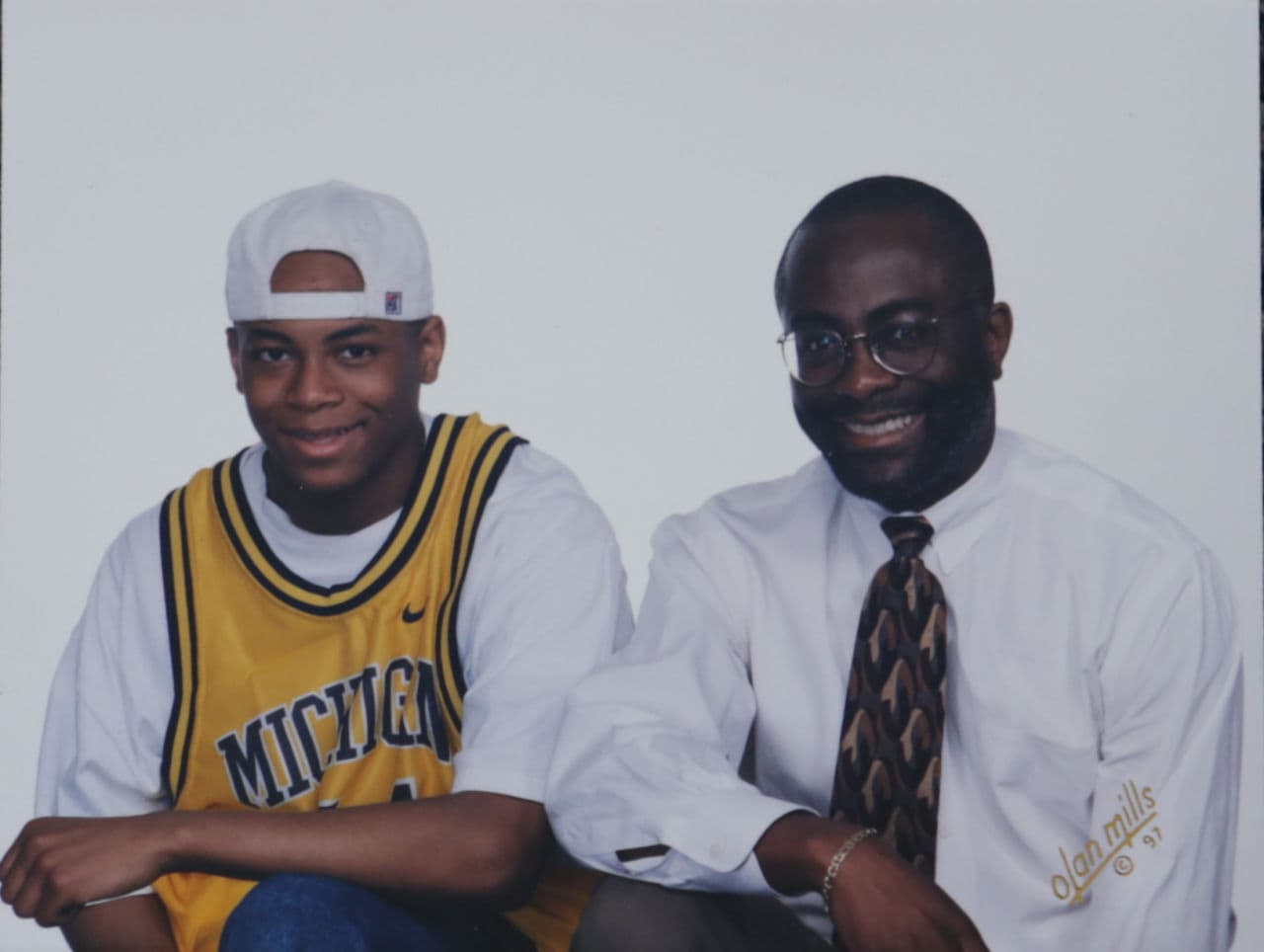

His father recalls lots of times going with Joseph to Horatio Harris Park, less than a block from the family's home. The elder Feaster doesn't remember any signs of mental illness in his son as a child.

"No, not at all. I mean, he was a happy kid," Feaster recalls. "He played here. He climbed the structures here. He would be with his sister and her friends. And he had a great smile."

Joseph's older sister nicknamed him "Smiley."

He played Little League baseball and then football in middle and high school in Newton, where he attended school through the METCO program. He got good grades and received awards for his academics and conduct, his father says.

'There's Nothing Wrong With Me': Denial Hampers Treatment

The first sign of any mental health issues was after Joseph returned from freshman year at the University of Pittsburgh in 2002. He had some type of psychotic break in which he was rambling incoherently and saying he was seeing and hearing things. Then he lunged at his father.

"His eyes were — it was like he had seen a ghost. So I left the apartment. I mean, I'm in tears at this particular point in time," Feaster says. "But I had the wherewithal and the knowledge to know that there was this process, Section 12."

Feaster wants to make sure other families know about and use Section 12. It's the state law that authorizes involuntary hospitalization of someone who poses a risk of serious harm to himself or others because of mental illness.

Feaster went to Boston Police, and they sent a special operations unit to Joseph’s apartment. After breaking down the door and using bean bags to stun Joseph, officers removed him safely.

He spent a short time in two hospitals and then started in an outpatient bipolar disorder program. But he wanted nothing to do with the medication and therapy advised by doctors, according to his father.

"There's denial. 'I don't have anything. There's nothing wrong with me.' The medicine changes [them]," Feaster says. "When you're in manic state, you can rule the world. Why would you want to take something that's going to bring you down?"

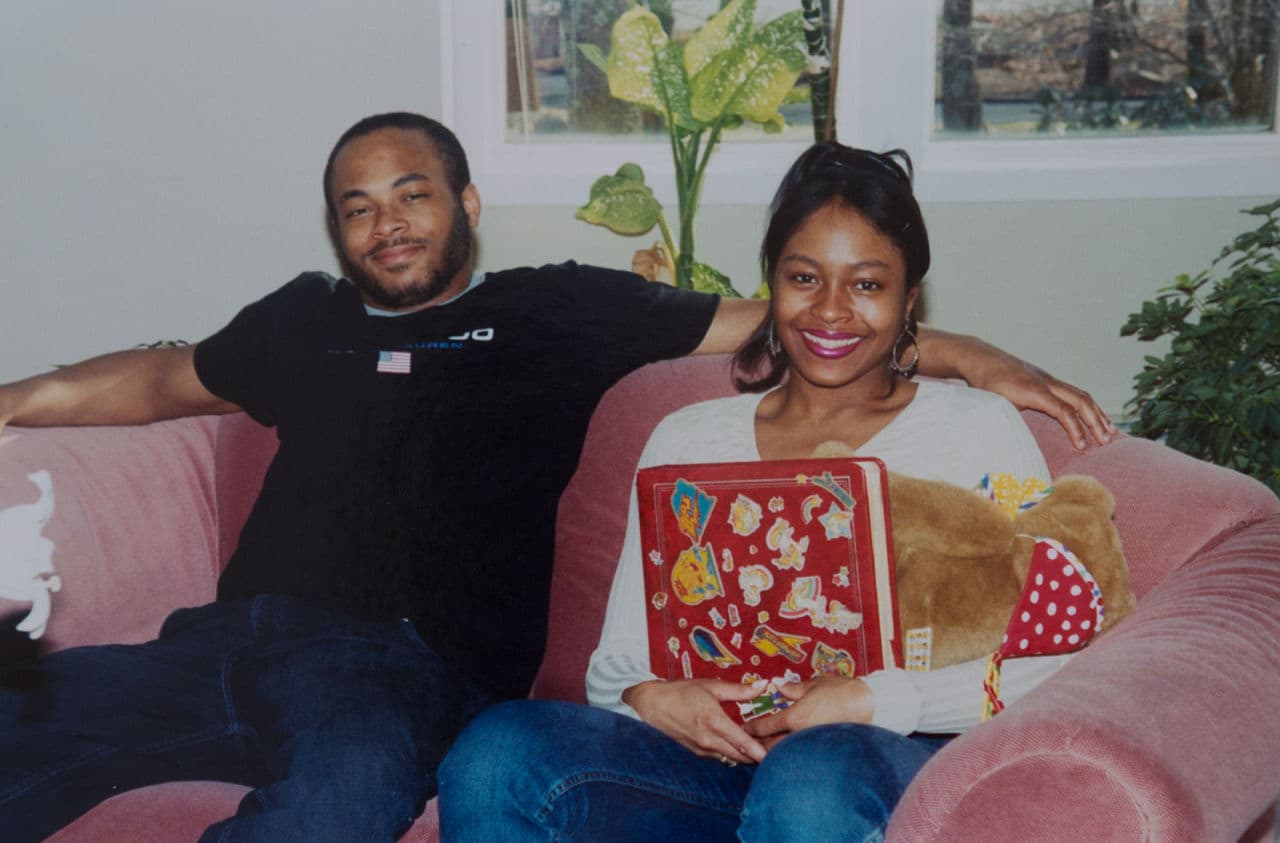

For the next seven years, his father says, Joseph showed no obvious signs of mental illness. He obtained a degree in political science from UMass Boston, while making a living selling DVDs and CDs online.

Then he got accepted to a new technological entrepreneurship master's degree program at Northeastern University. But during his first year he had another psychotic break. Police were again called to his Roxbury apartment, and this time he reacted in an extreme way.

"He jumped out of the third-floor window carrying a samurai sword, took off... and as a result of that, he's surrounded by all these police officers, guns drawn, [him] carrying this sword," Feaster recounts. "And apparently a sergeant tackled him, and that's what probably saved his life."

Feaster knows things could have ended much differently.

Joseph was hospitalized for a week or two, and his father says this was the first and one of very few times Joseph acknowledged he might have bipolar disorder. He told the doctors he would take his medicine, and he was sent home. But again, he didn't follow the treatment.

Joseph's next mental health break came more quickly, just seven months later. This time he took his own life.

Rising Concern About Suicide Among African-Americans

"I don't see any stigma from my son having had an illness," says Joseph Feaster, Jr. "People will talk about, 'Oh, so-and-so has breast cancer, so-and-so has lung cancer.' But if you say, 'Oh, wow, they had schizophrenia,' you don't hear folks talking about it. Well, my sense is [mental illness is] the silent disease in the African-American community."

There are several diseases referred to as "silent" epidemics among African-Americans. But Feaster says the community has largely avoided discussion of mental illness and suicide for specific reasons.

"It was long-held in the black community that that's not something that we — we're not going to kill ourselves, because of the religious belief, but also just, we just don't do that. That's a white person's illness. Well lo and behold, that turns out to be not true," Feaster explains.

Boston NAACP President Michael Curry, who's a friend of Feaster's, agrees.

"If a kid commits suicide in Roxbury or is the victim of a drive-by [shooting] in Roxbury, it should rock you to the core if you live in Wellington."

Michael Curry, president of the Boston NAACP

"There's always warning signs that something's getting worse," Curry says. "And the warning signs have been there in communities of color."

Curry says mental illness and suicide have taken a back seat to other issues of concern in the black community, like poverty, racism, and criminal justice. And those have taken a toll on mental health.

He's hearing from clinicians in Boston's African-American community that suicide is on the rise, even if it's not yet reflected in confirmed suicide statistics.

National data show the suicide rate for African-Americans has stayed fairly steady and significantly lower than for white Americans, though a recent study shows a suicide increase among black children.

But Curry says in assessing the risk of suicide in Boston's African-American community, he includes behavior such as so-called "suicide by cop" and drug abuse that leads to death. And no matter the method, he says, all of it demands action.

"What I have to remind people often is it's all of our responsibility. If a kid commits suicide in Roxbury or is the victim of a drive-by [shooting] in Roxbury, it should rock you to the core if you live in Wellington," Curry reflects "You've got to get off your butt, and you've got to figure out what your role is to be next to Joe [Feaster], to figure out how to save lives."

At Peace, Spreading A Message

Before Joe Feaster Jr. became an activist on the subject of suicide, he struggled not only with losing his son, Joseph III, but with concern about his son's soul.

"But my pastor said [Joseph] could still go to heaven notwithstanding, because of the illness, and I believe that's where he is," Feaster says.

With that sense of peace, Feaster, who now lives in Stoughton, started a support group of sorts at his church, Morning Star Baptist Church in Mattapan. About 30 people came to the initial meetings to talk about mental illness and suicide.

"When I started sharing about it, people started to share," Feaster recalls. "And I remember one person said, 'You know, I thought my son was just being lazy, that he wouldn't get up, he wouldn't go to school, he wouldn't do etcetera.' Well, [that person] never recognized that he was suffering from depression."

Attendance eventually dropped off, so Feaster has redirected his focus to working with organizations including the National Alliance on Mental Illness of Massachusetts.

And through it all, he says he often refers to his son in the present tense. He believes Joseph still lives in loved ones left behind, and through their fight for more awareness of mental health issues and suicide.

Resources: You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) and the Samaritans Statewide Hotline at 1-877-870-HOPE (4673)