Advertisement

Is It Possible To Prevent Suicide? 2 Psychiatrists Map Out The Ways

Suicide is awful, more common than you’d think and, in many cases, highly preventable.

Perhaps most important, in virtually every culture and every ethnic group on the planet, suicide is highly stigmatized. It therefore makes sense for the international health community to designate a day when we stop to actively contemplate this potent cause of misery and death. That's today: World Suicide Prevention Day, though the harsh facts surrounding suicide are so much bigger than a single day.

The statistics, from the International Association for Suicide Prevention, are staggering:

*There are an estimated 800,000 deaths every year throughout the world that are directly attributable to suicide.

*This number is probably under-reported, given the stigma associated with suicide, and the fact that deliberate, self-harming behavior is often misclassified as an accident. The teen that drives into a street lamp at 100 mph could very well be attempting suicide, and not be the victim of an automobile mishap.

*Suicide is the 15th leading cause of death on the planet.

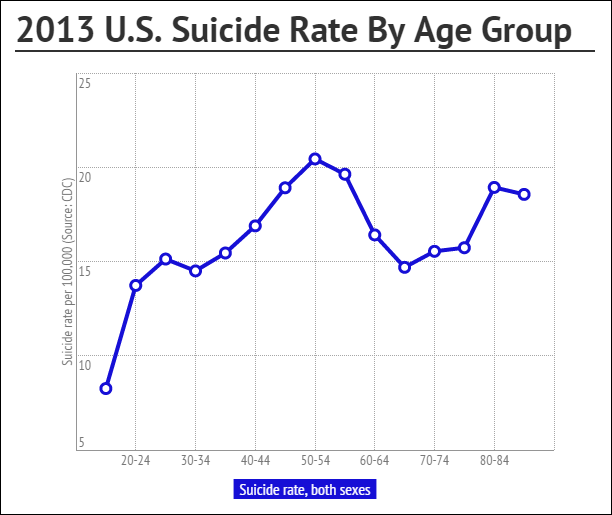

*Suicide is more common among older people (70 years of age and up), but also occurs in middle-aged and younger individuals at alarming rates.

*Lower income nations endure more suicides, but suicide remains a major cause of death in developed nations as well.

*Suicide has been tied to numerous psychiatric illnesses (mostly mood disorders), to difficult economic or traumatic situations and environments, to substance use disorders (both with and without addiction), to the loss of loved ones, and to a lack of good follow-up care following suicide attempts.

*The number one predictor of death by suicide is a previous attempt.

Why So Common?

In other words, we know a lot about suicide. So if we know so much, why does suicide remain so stubbornly common?

The answer to this question is actually much less concrete than we might think. Studies on post-suicide-attempt intervention are lacking and under-represented. Studies on pre-suicide-attempt intervention are also insufficient in generating a simple and generalizable prevention methodology. Moreover, the likelihood of creating a one-size-fits-all approach is minimal. This might be why we know less than we’d like to.

There are studies that show that email, phone and in-person communication following an attempt can make a positive difference, but these studies have relatively low numbers of participants and clearly need follow-up. We also have studies that show we can increase the understanding of suicide and its risk factors in high schools and colleges, but it isn’t clear whether this understanding leads to decreased suicide rates. We do know that treatment as usual — that is, telling someone to go to an appointment with a yet-to-be-met clinician following his or her discharge from an emergency room or hospital — falls short of other more personal interventions.

All of this points to a common flaw in the understanding of suicide.

Suicide isn’t a formal disease. We don’t treat suicide itself. We treat the causes of suicide.

Therefore, clinicians who focus entirely on the risk of suicide but fail to pay attention to its underlying causes may not minimize risk.

Just as we focus on decreased smoking to help prevent the incidences of lung cancer and heart disease, we need to more deliberately focus on and take preemptive action toward combating the causes and risk factors for suicide in order to truly decrease its tragic outcomes.

3 Culprits

The three main risk factors for suicide are relatively common in Western nations. They remain: a previous attempt; a psychiatric illness — most commonly depression; and a co-existing substance use disorder. Most interpret the presence of substance use as enhancing the impulsivity that can lead one to take the final steps toward a life-threatening event. This may be particularly true for adolescents and young adults, given the impulsivity that is a natural consequence of their immature brains, and their tendency to act on emotional triggers.

In non-Western nations, the risk factors are roughly the same, though poverty, impulsivity and anxiety, as well as social taboo, may play more prominent roles.

In other words, suicide has a lot of moving parts; prevention with certainty is extremely difficult.

So, where does all this leave us? What can we really do to prevent suicide?

First, the most basic, but not always easy, course: If you’re worried, if you notice something alarming, about a child, adolescent or adults, get help. Talk to your primary care doctor or a mental health professional. Don't wait.

In a broader sense, though, we need to focus on the risk factors.

Depression

We know that suicide is associated with depression, both treated and untreated. We know as well that treating depression significantly decreases the rate of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide. This is true for all ages, but depression is much more likely to be missed in children and adolescents, as it tends to look a lot different. Although children and teens with depression may have a depressed mood, they also might be irritable or agitated. Sleep and appetite, commonly decreased in adults, may actually increase in younger individuals. Finally, because each episode of depression, and especially each episode of untreated depression, worsens subsequent bouts with the illness, early detection and ample treatment is absolutely essential. To this end, we must aggressively detect depression if we are to make any progress in the battle against suicide.

Mood Disorders

There is evidence that even with ample detection, adequate treatment of mood disorders can fall short of the existing standards of care. This is due to lack of access, reluctance to use antidepressants (especially after the addition of the black box warning), lack of available psychotherapy (or an unwillingness to participate in psychotherapy) and, of course, stigma.

Substance Use

A substantial proportion of suicides are associated with the abuse of substances. We need to be better at helping others understand that mixing substances with a low or angry mood disinhibits what might otherwise be the self-control to prevent self-harm and death.

Related Risks

Other problems are also associated with suicide. For instance, we know that the presence of an eating disorder is associated with both attempted suicide and death by suicide. In fact, the most common cause of death in anorexia nervosa is suicide, especially when coupled with alcohol use. The longer an individual suffers from anorexia nervosa, the greater the risk of death by suicide.

We also know that when you control for coexisting illnesses like depression, anorexia drops out in many studies as an independent risk factor. This means that among those who suffer from anorexia, the presence of depression is particularly alarming and requires special vigilance. Also worrisome is the fact that bulimia nervosa is associated with suicidality in the absence of any coexisting mood disorders — meaning that all individuals with eating disorders require focused suicide screening.

Increased concern for head injuries has elucidated clear relationships between concussion, traumatic brain injuries and increased suicide risk. Whenever anyone is suspected of suffering from a head injury, it is essential that we screen for suicidal thoughts and coexisting risk factors.

The Social Network

Then there are the social factors. There are entire books written about the social factors that contribute to suicide. Poverty, crime and trauma from war, famine, domestic assault and sexual attacks have all been implicated.

Sociological phenomena such as copycat suicides and suicide clusters also pose potent risk. Interestingly, though not surprisingly, all of these have in common a lack of personalized social support for those who are suffering. Therefore, any approach to alleviating these risks must occur in a warm and highly personal manner. In fact, telling large groups of suffering people that you are going to help them has been found to actually increase risk. On the other hand, if we devote the time and resources to be personally available, the rate of suicide goes down even in difficult social circumstances. This has been found in settings as varied as high schools and military gatherings.

So, we can, it turns out, do a lot. Moreover, much of what we can do is what we ought to be doing anyhow. Screening for preexisting risk factors early in life is essential.

We need to detect and treat psychiatric illnesses more effectively and earlier in life. We need a better approach to the social factors that haunt us and put us at risk for suicide. We need to understand and spread the word more effectively about the risk factors for all suicides.

And, most importantly, we need each other. Every single study of suicide and its causes shows that through open, personal and informed communication, the rate of suicide can be decreased. We’re pack animals. We need each other.

Dr. Gene Beresin is executive director of The MGH Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Steve Schlozman is associate director of The MGH Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds and an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.