Advertisement

Study: Thousands Of Injuries As Ziplines Proliferate, Younger Kids Most At Risk

Hannah Weyerhauser was 5 years old, playing on the zipline at her family's house in New Hampshire, when she started complaining that her older cousins and siblings were going faster than she was. So her mother, Annie, gave Hannah an extra big push. But when Hannah sped to the end of the zipline, she stopped short, flew into the air, did a back flip, and landed on her neck.

"For a few minutes she was really pale and out of it," said her mother, a Boston doctor (and a friend of mine). She called an ambulance, and paramedics put a collar on Hannah's neck on the way to the local emergency department. Ultimately, the little girl was fine, although she probably had a minor concussion, her mother said. But Annie shudders as she thinks of what could have happened: "If she had fallen a little differently she could have broken her neck."

Others are not so lucky. Increasingly, zipline disasters are making the news. A 12-year-old girl in North Carolina died after falling off a zipline at the YMCA's Champ Cheerio in June. And last year, a 10-year-old boy died after a backyard zipline accident in Easton, Massachusetts, in which the tree holding the line fell on the child.

Indeed, injuries related to ziplines are rising as the lines proliferate, according to a new report: In 2012 alone, there were over 3,600 zipline-related injuries, or about 10 a day. The study, which researchers say is the first to characterize the epidemiology of zipline-related injuries using a nationally representative database, found that from 1997-2012, about 16,850 zipline-related injuries were treated in U.S. emergency departments.

The report on ziplines (first used over a century ago to transport supplies in the Indian Himalayas) found that most of the injuries resulted from falling off the zipline, and many involved young children. I asked one of the study authors, Tracy Mehan, manager of translational research with the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Ohio, a few questions about the report, published in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

Here, edited, is what she said.

Rachel Zimmerman: Are you surprised by this sharp increase in zipline injuries?

Tracy Mehan: The number of commercial ziplines grew from just 10 in 2001 to over 200 by 2012. When you include the number of amateur ziplines that can also be found in backyards and at places like outdoor education programs and camps, the number skyrockets to over 13,000. The increase in the number of injuries is likely due largely to the increase in number of ziplines and shows this is a growing trend.

What are the most common types of injuries?

The majority of zipline-related injuries were the result of either a fall (77 percent) or a collision (13 percent) with either a tree, a stationary support structure or another person. The most frequent type of injuries were broken bones (46 percent), bruises (15 percent), strains/sprains (15 percent) and concussions/closed head injuries (7 percent). Approximately one in 10 patients (12 percent) were admitted to the hospital for their injury.

Though the rate of injuries while ziplining is relatively low, when injuries do occur they can be quite serious. The high rate of hospitalization is consistent with what we see for adventure sports and reflects the severity of the injuries associated with this activity.

The study found that it's primarily younger kids getting hurt. Why is that?

Children younger than 10 years of age accounted for almost half (45 percent) of the zipline-related injuries with youth ages 10-19 accounting for an additional 33 percent.

For the younger age group, almost 90 percent of the injuries were the result of a fall. It may be that they lack the upper body strength needed to hold onto the zipline handles for the whole ride, that they are not using a harness, or that the type of braking system that is being used may cause them to lose their grip and fall if there is a sudden stop.

Why did you pursue this study in the first place?

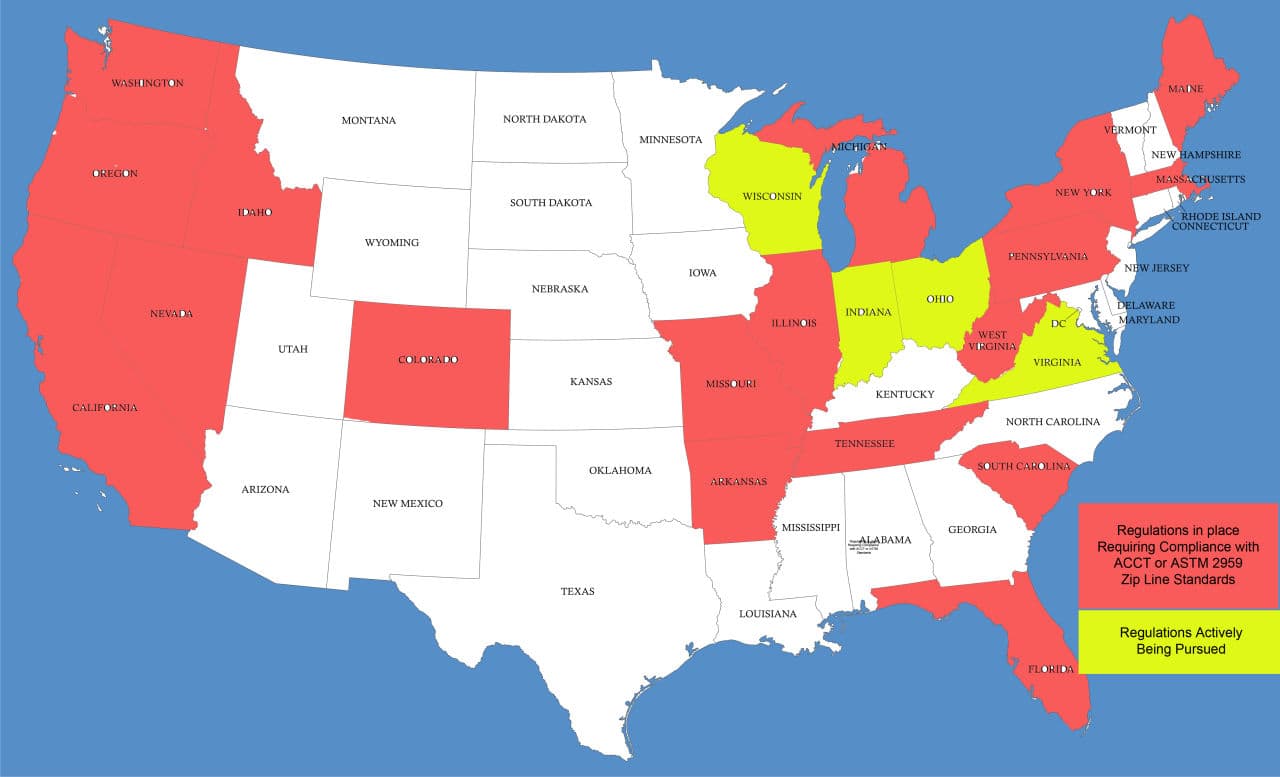

We noticed the rapidly growing number of ziplines popping up around the country. When we started looking into it, we realized that these ziplines are not regulated in every state. We also found that states are following different sets of safety standards and that the standards ziplines are required to meet can vary even within a state. We’d like to see a uniform set of safety standards adopted, implemented and enforced in each state. Having one universal zipline standard would make inspection and enforcement easier, leading to a safer experience for the rider.

Is there any momentum in any region of the country to tighten up regulations on ziplines?

We are not aware of anyone taking initiative on this currently.

Your study includes injuries only, not deaths, right?

Our research only looked at injuries treated in hospital emergency departments. If the patient was not seen in the ED, we do not have information on their injury. Because many deaths are either called on site or in the ambulance, they are not recorded in the ED system.

What should parents know before letting their kids get on a zipline?

The best thing to do is research before you ride.

-- Only go on ziplines that have well-trained staff and can show you that their ziplines meet industry safety standards.

-- Follow all posted rules and instructions from staff.

-- Always wear the proper safety equipment (helmet, harness and gloves).

-- If you are considering having your child ride, ask the zipline operator if they have age, height or weight restrictions and make sure to follow their recommendations.

-- Do not use homemade or backyard ziplines. Improper installation, maintenance or use can result in serious injuries and even death.

Eighteen states currently have regulations for ziplines, says James Borishade, executive director of the Association for Challenge Course Technology (ACCT), a organization that develops standards for the challenge course industry, which includes ziplines, aerial adventure and ropes courses. Borishade said the organization supports "responsible regulations" including annual inspections, daily equipment checks, operator training and an operations manual.

One issue, he said, is that different standards are appropriate for different settings, for instance, a zipline at a school or camp is very different from one on a cruise ship or ski resort. But, he adds, the industry is still fairly new and adjusting to its own success.

To reflect these changes, he said, the group tries to revise its standards every two to three years, and is currently involved in updating the standards for the challenge course industry.

At the moment, he said, the ACCT does not have standards related specifically to backyard ziplines: "However, we strongly recommend that any and all courses be built by qualified professionals."

Readers, have you had an injury or close call on a zipline? What happened?