Advertisement

Ethical Dilemma: Do I Game The System To Get My Patient A Heart?

Imagine your heart is failing. It can no longer pump enough blood to your vital organs. Even minimal exercise tires you out, and you’re often short of breath when lying flat. Your lungs are accumulating fluid, and your kidneys and liver are impaired.

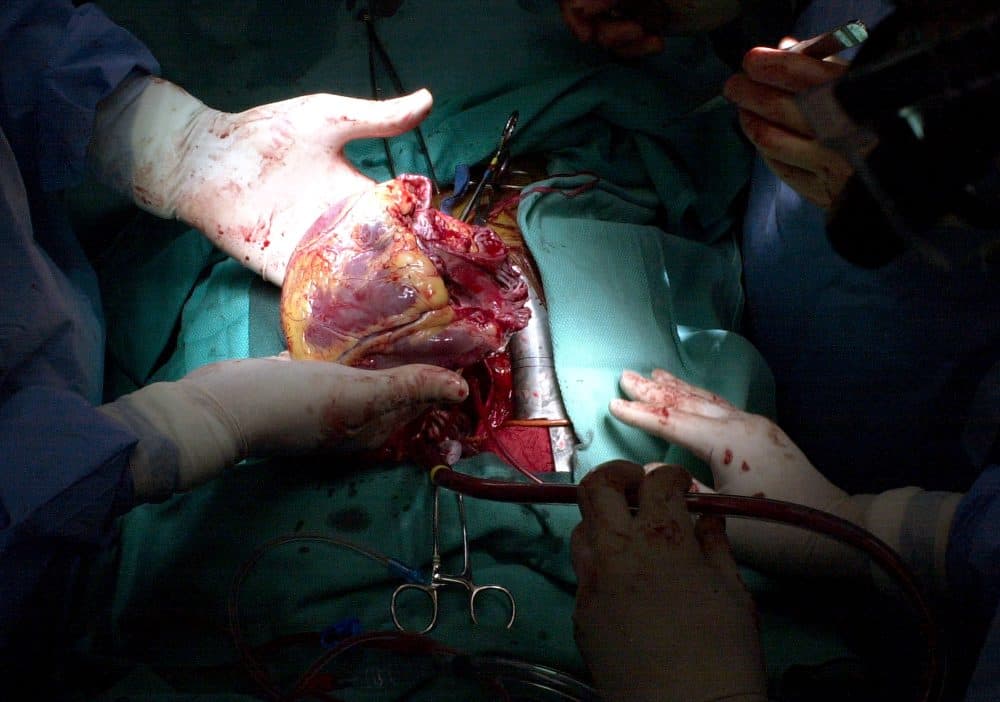

You’ve been hospitalized and started on an inotropic agent, an IV drug that improves your heart muscle’s ability to contract. It’s helped, but it’s not a long-term solution. You need a new heart, and you’re a good candidate.

But there is a problem: a chronic shortage of donor hearts. In 2014, for example, about 6,950 Americans were approved for heart transplants, and only about 2,250 donor hearts became available. You need to move higher up on the list to get a heart.

Now imagine I’m your doctor. I want to help you get you a heart. But I face an ethical dilemma: Do I ramp up your medical treatment, even beyond what I consider necessary, to bump you higher on the list?

Aiming For Status 1A

This is the system we have to navigate: The United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, has established criteria to make sure that donor hearts go to the patients with the most severe disease. The criteria are based on which treatments a doctor has seen fit to prescribe, on the assumption that they’re a good indication of how critical your illness is.

Generally, that's a good assumption. Except that the system itself creates a perverse incentive.

Where you are on the waiting list for hearts depends on your "status." If you weren’t getting that IV drug, you’d be considered “Status 2.” Your median wait time for a heart would be 630 days. Not good.

But you’re on the IV drug, so you’re considered “Status 1.” Better. But Status 1 is divided into two categories: If you’re on low doses of the inotropic agent, you’re classified “1B.” That means your median wait is 301 days.

But if you’re in an intensive-care unit, receiving high doses of your IV drug, and have an indwelling pulmonary-artery catheter to monitor cardiac performance, you’re "Status 1A." Your median wait is just 110 days.

So you’re unlikely to get a heart any time soon unless you can be listed 1A. In your case, if you weren’t up for a transplant, there would be no call to implant a pulmonary-artery catheter in you; they’re uncomfortable and have a risk of infection. There would also be no call to raise your dose of inotropic agent; higher doses can increase the risk of sudden cardiac death with long-term use.

But these risks are outweighed by the danger of having to wait three times as long for a transplant, during which your condition may deteriorate; you may need a mechanical pump or an artificial heart, both of which entail major cardiac surgery and potentially serious complications. And you may die.

So: even though these measures aren’t medically indicated, do I admit you to intensive care, insert a pulmonary-artery catheter and raise your dose of inotropic agent to qualify you for 1A status? And if I do, is it ethical?

The Transplant List Is Zero-Sum

The American Medical Association, in a statement on the allocation of limited medical resources, asserts that “a physician has a duty to do all that he or she can for the benefit of the individual patient."

And dishonesty on behalf of others can be virtuous. Ludvik Wolski, a Roman Catholic priest in Otwock, Poland, forged certificates of baptism to save the lives of Jewish children during the Nazi occupation.

If I insert a pulmonary-artery catheter in you to help you get a donor heart, I might be tempted to believe I’m acting similarly.

But there is an important difference between the situation Wolski faced and mine: Wolski’s actions had no adverse consequences for other Jewish children in the community.

In contrast, the transplant list, with its vast excess of prospective recipients, is functionally a zero-sum game. If I increase your odds, I decrease another patient’s. And so I provide no overall benefit for the heart failure population.

So I might be inclined to resist over-treating you here — if I’m confident that other doctors are resisting as well.

And there’s the rub: If I have reason to believe that my counterparts at other transplant programs are escalating their care to move their patients up on the list, then I may be putting you at a disadvantage by refusing to do likewise.

And I do have reason to believe that, based on an editorial in the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation commenting on how invasive treatments are being overused to game the transplant system, as well as a more recent commentary in the same journal noting that when the criteria for transplant status changed, medical practice evolved in step with the new criteria.

So my personal integrity ends up in direct conflict with my responsibility as your advocate.

In the big picture, this system increases the use of medically unnecessary treatments, driving up both medical costs and patients’ risks of complications.

And perhaps worst of all: When “gaming the system” goes from being an aberration to a standard strategy — when, as the authors of the above-mentioned commentary write, "treating to the priority is almost as fundamental as studying to the test" — then dishonesty becomes normal.

This cannot be good.

New Rules

The United Network for Organ Sharing is now considering a new system for allocating donor hearts, with many more priority stratifications.

Among the new criteria proposed for determining a patient’s wait-list status are measures that are far more aggressive than pulmonary-artery catheters and inotropic agents: the insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump or temporary circulatory assist device and the use of extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation.

Using these measures as criteria should be better at selecting patients with the most severe disease.

But that’s what we thought about pulmonary-artery catheters and inotropic agents. And these new criteria, too, are “gameable.” Some transplant cardiologists and surgeons are already expressing concerns about the potential use of intra-aortic balloon pumps inserted through the subclavian artery that will allow patients to walk about while waiting for transplants.

The same perverse incentive to escalate care will remain — and so will the ethical dilemma it creates.

Matthew Movsesian, M.D., a cardiologist, is a professor at the University of Utah School of Medicine in the Division of Cardiovascular Disease.