Advertisement

Spike In Organ Donations Parallels Overdose Deaths, Offering Comfort And Compounding Grief

Resume

For just over 24 hours, on the final day of June 2015, Colin LePage rode waves of hope and despair. It started when LePage found his 30-year-old son, Chris, at home after an apparent overdose. In a panic, LePage tried Narcan and CPR, then raced with EMTs to a hospital in Haverhill.

"When I first walked into the emergency room ... I was getting the impression that my son was already gone," LePage recalls. "But while we were there in the hospital and they were working on him, um, is when they told me they had a heartbeat and they were getting signs."

Signs that Chris’ brain might still be alive. Strapped to a gurney, Chris was rushed by helicopter to a Boston hospital for more specialized tests. Between efforts to stabilize his temperature and blood pressure, a doctor or nurse mentioned to LePage that his son had agreed to be an organ donor.

"There was no urgency or, 'Hey, you need to do this,' " LePage says, his voice quavering. "I could see genuine concern and sadness that this had happened, that he mattered to someone. It wasn’t that, 'Well, we’re going to be able to use his organs for someone else.' "

The next morning, after another round of tests showed no signs of brain activity, LePage said goodbye to the son who’d been revived but wasn’t fully alive.

"I sat in a chair with him, and held his hand," LePage says. "It wasn’t clinical. It didn't feel like someone's gaining something here. I knew that someone was, and that’s comforting that someone else has been able to have a little piece of my son and some of their pain is not what it used to be."

Chris’ liver is at work inside a man LePage knows only as David, a 62-year-old pastor.

LePage reads the end of a letter sent earlier this year via the New England Organ Bank:

A part of him now lives in me and whenever I stand to speak, I say thank you, Lord, for this family, who I am connected to in a way that is nothing short of a miracle. I pray someday we may meet, God bless you, David.

LePage drops his hands, holding the letter, into his lap.

"I just haven’t had time to write back to those powerful statements," he says with a sigh. "But I will, I will do that soon."

A Tragedy's 'Unexpected Life-Saving Legacy'

LePage’s experience is happening all too often, as patients addicted to heroin or other opiates take too much, stop breathing, and are declared brain dead.

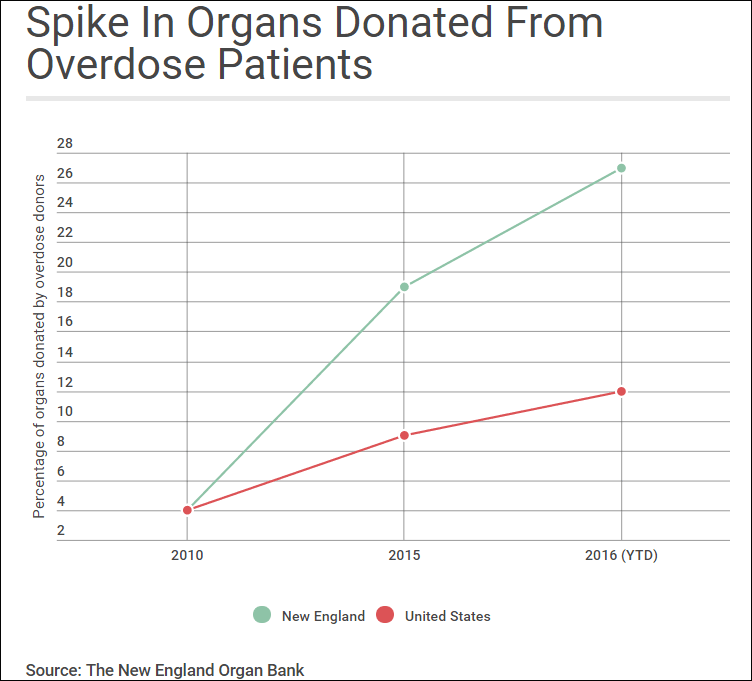

In 2010, one in 20 organs donated in New England was from an overdose patient.

"This year so far we are at 27 percent, which represents just over one in four donors that have died of a drug overdose," says Alexandra Glazier, president and CEO of the New England Organ Bank. "It’s remarkable and it’s also tragic. We see this tragedy of the opioid epidemic as having an unexpected life-saving legacy."

More so in New England than in other parts of the country. The number of organs donated by drug users in New England has increased from 8 in 2010 to 69 so far this year; across the U.S., the increase is less dramatic, from 341 in 2010 to 790 through Aug. 31 of this year.

It’s not clear why. Overdose death rates are high in New England but not the highest in the country. Glazier says the 12 transplant centers in this region may be more aggressive about finding a match for patients with failing hearts, livers or kidneys.

Organ Demand Rises Still

At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, the number of patients receiving a liver transplant has roughly doubled in the last three to four years. Hospitals are required to test organs and warn patients if there is a risk of contracting HIV or hepatitis B or C. That risk may be less troubling for patients these days because there are drugs to treat these viruses if patients become infected.

Some patients in need of organs still hesitate at the idea of accepting a liver or kidney donated by a drug user. But not at Lahey, where Dr. Mohamed Akoad chairs the department of transplantation.

"Most of these patients trust the fact that these donors are tested and they understand that their chance of dying while waiting for an organ is high," he says.

Akoad says Lahey has not had any cases of HIV or hepatitis B or C transmission in recent years.

That’s the case at Mass General in Boston as well. Dr. Jay Fishman, associate director of the hospital's transplant center, says an organ from someone who used drugs is not necessarily risky and may even be healthier than other options.

"You have to remember that as awful as this outbreak is, these are younger people who are dying often with needles in their arms and many of them were first-time drug users," Fishman says. "They weren’t all addicts."

Despite this increase in available organs, there’s no sign that supply is keeping up with demand for organs from aging Americans, or those with a chronic disease.

"The number of people on the waiting list is increasing faster than the number of donors, even with the increases related to overdoses," says Dr. David Klassen, chief medical officer at the United Network for Organ Sharing, which tracks and manages organ donations in the U.S.

There are likely many more organs available from the victims of drug overdoses than those collected. Some patients addicted to heroin or other opioids don’t carry a license, haven’t spoken to a family member about their end-of-life wishes, or aren’t in touch with family members who could give consent to donate an organ.

“I’ve never heard anyone talk about organ donation as a possibility. I’m not sure it’s on their radar screen,” says Dr. Jessie Gaeta, chief medical officer at the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

And Gaeta says she isn’t sure how she would suggest organ donation, even to her high-risk patients.

“It’s really nihilistic to say that to someone in their early 20s,” Gaeta says. “I have so much hope for my patients, yet if someone does die and there’s a chance for their organs to be helpful, that’s one good thing to come of a death like that.”

For many mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers who’ve lost someone to an overdose, organ donation is a nearly taboo topic. It triggers feelings of guilt, anger and despair.

Debbie Deagle sat next to her son Stephen’s unresponsive body for six days before agreeing to turn off his respirator.

"I laid on top of him, all morning, before they took him," Deagle says, weeping. "I had my head on his heart, just so I could hear that beat, and they had to peel me off."

More than a year later, Deagle is still haunted by questions: Should she have asked for another opinion about the scans of Stephen’s brain?

"Never in a million years do you ever visualize kissing your child whose heart’s beating and having to watch them wheel that stretcher away and know they’re going to cut him open and take out a beating heart," Deagle says.

The transplant patient who received Stephen’s heart did not make it, leaving Deagle with the feeling her son had died again. She’s written to the patients who received Stephen's liver and kidneys, but has not heard anything back, yet.

This segment aired on October 12, 2016.