Advertisement

Fantasy No Longer: Blood Biopsies Detect Tumor DNA, Could Catch Cancer Earlier

Resume

This story is part of our "This Moment In Cancer" series.

Jennifer Hendryx has been living with incurable cancer for nearly two years, ever since she found out at age 35 that her horrible back pain was actually cancer that had spread from her breast.

She gets so many medical tests these days that having one extra vial of blood drawn is no big deal.

"Filling up a big vial of blood in the name of science," she narrated as the dark red tide slowly rose in the plastic tube hooked to the needle in her arm. "Come on, blood, go go go!"

This extra vial of her blood was making a bit of history, though. It would travel from Fairview Hospital in Cleveland, where Hendryx lives, to the Cambridge-based Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, one of the world’s leading centers of research on genomics.

And there, when researchers analyzed its DNA, it would add to the burgeoning science of blood biopsies — efforts to track cancer with just a blood test.

Among the many on-the-cusp technologies fueling excitement in the cancer sphere, former Vice President Joe Biden singled out blood biopsies when he passed through Boston recently.

"I find it absolutely incredible and exciting that a marker in your blood can tell you whether or not you have a particular cancer," he told a crowd gathered to hear him talk about the Obama administration's Cancer Moonshot.

Jesse Boehm, assistant director of the Broad Institute's cancer program, says he believes blood biopsies are changing the field of genomic medicine — customizing your care to your DNA — faster than any other approach.

"They've gone from fantasy maybe five years ago," he said, "to, 'You know, smells interesting' a couple of years ago, to now there are tests and we've shown you can get the whole thing from the blood."

The "whole thing" he's talking about is the DNA "fingerprint" of a tumor — which mutations it carries, what's driving the cancer.

Traditionally, to get that DNA, doctors have had to surgically remove a chunk of tumor, or insert a long, hollow needle into the patient's body. Seeking it in blood instead long seemed highly improbable.

"It just seems so far-fetched, that out of a small tube of blood you could have a lens into a tumor somewhere else in the body," said Todd Golub, the Broad's scientific director. But "it turns out that it's really possible now, and is going to become a really powerful part of our armamentarium against cancer."

Blood biopsies seemed so far-fetched because it's incredibly rare for whole cells to escape the tumor and float in the blood. But new DNA technology can find and analyze tiny fragments of tumor DNA -- what's called "cell-free" DNA -- in most patients. It's akin to the new prenatal tests that can find bits of the embryo's DNA in the mother's blood.

10 Billion Bits Of Data

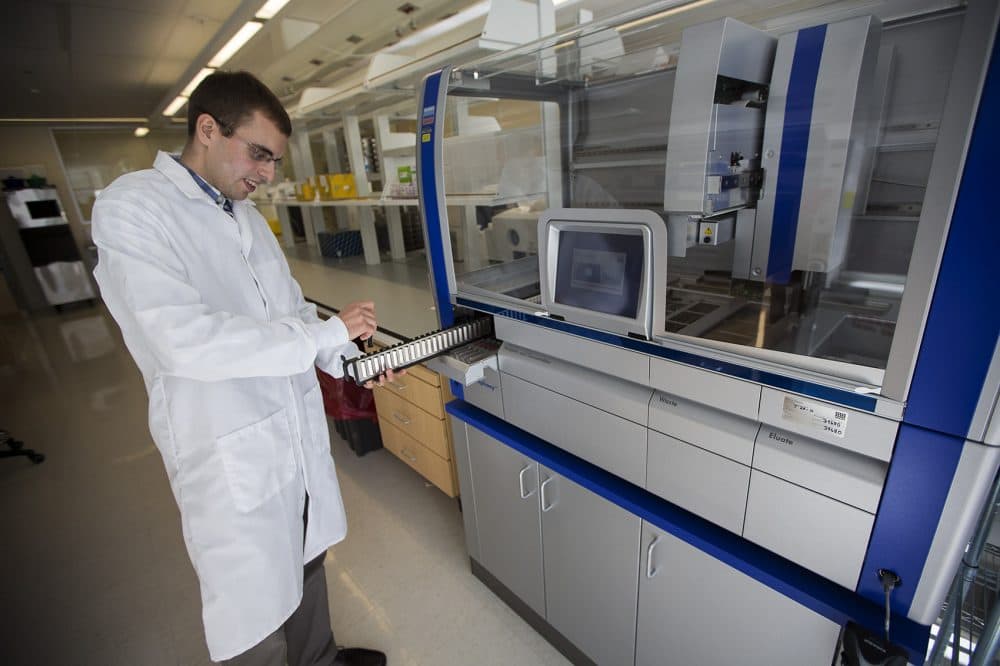

In his lab at the Broad Institute, Blood Biopsy Group leader Viktor Adalsteinsson started with those fragments of DNA — hundreds of millions, even billions, in each tube of blood.

If you think of your whole set of DNA as a book, its letters are the bases — the As, Cs, Ts and Gs. The Broad's DNA sequencing machines analyze and reanalyze those letters looking for cancer's telltale spelling changes among a sea of normal words.

"We typically look at 10 billion bases' worth of data per sample," Adalsteinsson said, "to figure out which positions in the genome are indeed altered in that sample."

("It makes me tired," I couldn't help but comment. "It makes the computers tired, too," he laughed.)

Hendryx, who had that blood draw earlier, is one of the first patients to send her blood to Adalsteinsson's lab as part of the Broad Institute's Metastatic Breast Cancer Project.

It's a new program that lets patients anywhere in the country volunteer to share their medical records, tissue samples and now blood for analysis. The results can't affect their treatment at this point, but they can help advance research.

Adalsteinsson has a special stake in the project: His mother had metastatic breast cancer.

"So this is actually something I'm very personally invested in," he said, "and a major reason why we've built what we've built."

They've built not just a lab but a community of patients: More than 3,000 women have signed up. And of scientists: nearly 100 researchers and doctors, from an array of top Boston hospitals and universities that often compete, who come together regularly to work on blood biopsies.

Dr. Nikhil Wagle, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, hopes ultimately to use blood biopsies to guide how he treats patients: first, to decide which drugs to use based on the tumor DNA; and then, with repeated blood tests over time, to see how well the treatments are working.

Say a biopsy finds that the amount of tumor DNA in the patient's blood is rising again. "That tells me, 'Oh, no, the tumor is growing again,' " Wagle said. "Maybe then I look at what the composition of that tumor DNA is again, and it tells me either what different regimen to use or what additional drugs to add."

So blood biopsies could help oncologists like Wagle fight cancer that evolves resistance to treatment, leading to heartbreaking relapses. That resistance remains a central challenge, even with new breakthrough drugs.

But it's a long way from research to the clinic, Wagle cautioned, and "everything I said just now requires a ton of work to be able to make it a reality."

A Hail Mary Pass

That's why for all the buzz around blood biopsies, there's also caution and some skepticism. These are early days yet. Blood biopsies still face some technical challenges — for example, a recent Massachusetts General Hospital study found that they could detect early liver cancer, but only with two-thirds accuracy. And the field still needs solid proof that using blood biopsies in treatment does help patients live longer.

Greg Simon, the former executive director of the cancer moonshot under Biden, called blood biopsies a Hail Mary pass, "because you might get it right a few times early on, but it's not yet a system."

"It's not science fiction," he added, "but it's not a strategy yet to go out and save lives all over the country. But it might be. And some people think it will be."

Some people, in fact, are betting a lot of money that it will be. A San Francisco startup called Grail announced last month that it had commitments for over $1 billion from backers of its work to develop a blood test that can detect even early cancer.

But screening to try to catch cancer early — mammograms, PSA tests for possible prostate cancer — is a notoriously tricky task, fraught with the risk that it will pick up tumors that would never have amounted to anything.

"I don't think we should rush to assume that blood biopsy as a screening test is either going to be technically feasible or even advisable," said Golub, the Broad Institute scientific director.

For now, Broad researchers say, one big question is whether blood biopsies can be scaled up to expand the pool of patients whose treatment is guided by their tumor's DNA -- about 15 percent of cancer patients right now.

That would fit in to how the Broad Institute's Boehm sees the future of cancer treatment.

"The path toward curing cancer isn't a magic bullet, but is expanding the number of individuals who are getting their genetics analyzed," he said. "And what'll be 15 percent today will be 25 percent tomorrow, and that will continue to expand, until it includes everyone."

Hendryx donated her blood in part to bring that future closer for her 9-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son, she said. "I would love for them to live in a world where they don't have to go through what I'm going through."

She's about halfway through the three-year lifespan doctors told her to expect. And her fingers are crossed, she said, that the research will bear fruit fast enough for her to live many more years — maybe even long enough to see cancer eradicated once and for all.

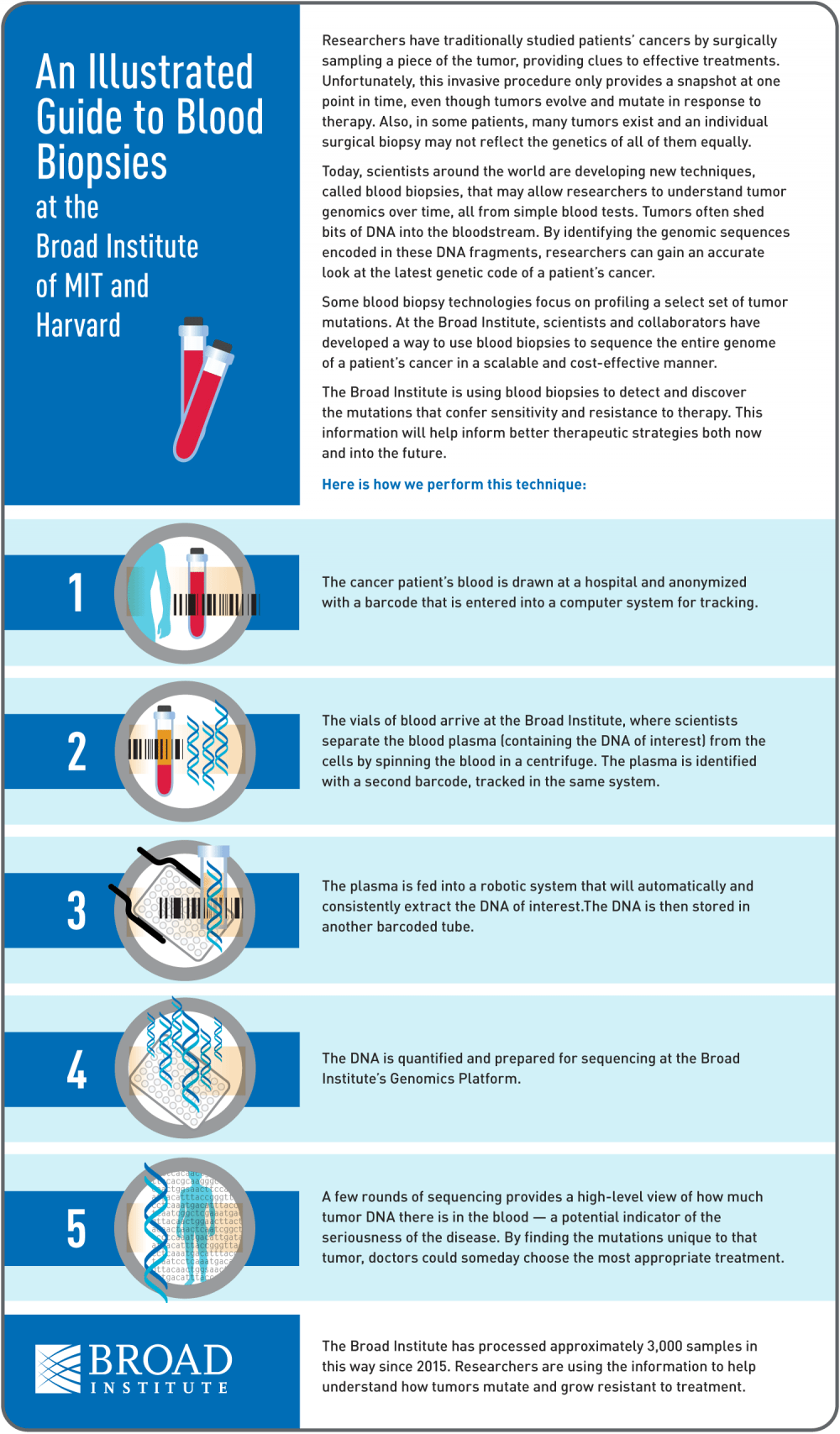

Various research centers and companies are working on blood biopsies, but here is what happens at the Broad Institute (click to enlarge; here's a PDF version):

Do you have a question about cancer research, treatment or care that'd you like us to investigate? Ask it here.

This segment aired on February 1, 2017.