Advertisement

Boston EMS Reports Opioid Overdose Deaths Were Way Up In 2017

Resume

In Massachusetts, where at least five men and women are dying from an opioid overdose every day, everyone tied to the epidemic is desperate for signs of hope.

They got some late last year, when state data showed an estimated 10 percent decrease in overdose deaths for the first nine months of 2017, compared with the same period in 2016.

But data, and conversations with doctors, suggest the opioid epidemic is getting worse, not better — at least in the state's largest city.

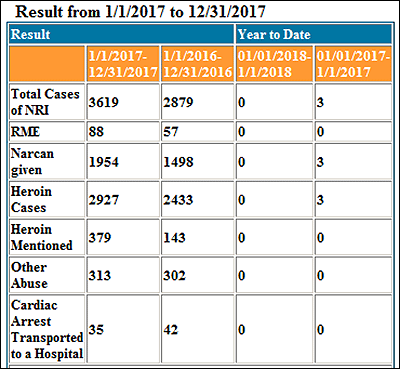

We offer the chart here with caveats: It's from Boston EMS and so doesn't capture all overdoses or deaths in Boston; the cause of death is not confirmed by a medical examiner; and the categories, such as "heroin mentioned," are based on observation by EMTs.

Still, the numbers fit what many doctors, nurses, drug users and their families are seeing in Boston. And they are alarming.

- Calls to EMS involving heroin, or what was suspected as heroin, were up 20 percent in 2017, compared with 2016.

- Calls during which Narcan, the drug that reverses an opioid overdose, was given were up 30 percent.

- Deaths, seen as "RME" (referred to medical examiner) were up 54 percent from the year before. EMS attributes those to opioid overdoses.

It's not clear what's happening in Boston, but doctors, drug users and first responders all say they are worried about more and more deadly versions of fentanyl.

"Much has been made about the potency of the illegal street drugs that are out there, and reports that the percentage of potency in the fentanyl has been going up over the years," says Boston EMS chief Jim Hooley.

The Drug Enforcement Administration says new, stronger mixtures of fentanyl are coming regularly into the United States from China and Mexico. Massachusetts State Police say they found carfentanil in 29 samples tested in 18 cases last year. (Those findings do not include Boston, which conducts its own tests. We'll update this story with information from Boston police if and when we get it.)

There are more possible reasons that increasingly potent fentanyl may be driving up overdose deaths. Dealers are adding it to all kinds of drugs: cocaine, fake pain pills, methamphetamines and weed. And fentanyl, which produces a more intense high than heroin, wears off more quickly than heroin.

"Once it wears off and you begin craving more, you're going to use it again," Hooley says. "The fact that you're using more times per week, you're increasing the risk that any one of those overdoses could be fatal."

In Boston's South End, drug users say everything they buy is laced with or is predominately fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that's cheaper than heroin, which is from a poppy plant.

Dealers are "putting more fentanyl in the bags than there is heroin," says Anna, a woman who says she hasn't used drugs from three weeks. "People go into detox and give a urine sample and get denied because there's no heroin in the sample." Many urine tests can't detect fentanyl.

Anna and her friend Nichole say carfentanil is available in Boston.

"It's around," Nichole says. "I don't think it's hit as hard as the regular fentanyl, but it's here."

We're not publishing last names for Anna or Nichole because both women have been engaged in illegal drug use.

Some doctors in Boston noticed a spike in overdoses, perhaps caused by an especially potent batch of opioids, in the late summer of 2017. In mid-September, the Boston Public Health Commission issued a warning to hospitals and clinics about a 50 percent increase in drug-related calls to EMS in August, as compared with July. The commission said that uptick continued into September.

In Boston clinics and hospitals, doctors said they found themselves using more naloxone (Narcan) than ever before to revive patients.

"The most I heard was from colleagues who used something like 14 doses of naloxone," says Dr. Sarah Wakeman, medical director of the substance use disorder initiative at Massachusetts General Hospital. "We definitely were hearing from people who in the past would have used one or two doses and now are using five, six, seven, eight."

There's no clear reason why this picture in Boston looks so different from that presented by the state in November.

The Baker administration says there are many nuances that affect the reporting of overdose death data and the projections it makes in an effort to track the state's opioid epidemic. A spokeswoman says the late summer to early fall surge in Boston was included in its most recent estimates that anticipate a 10 percent decrease in deaths statewide. An update on fatal overdoses in Massachusetts is due out next month.

So is the epidemic getting better or worse in Boston, and what does the answer mean for ongoing efforts to curb opioid addiction?

"Anyone who is working on the front lines, treating these patients every day — I don't think anybody who is doing that is going to feel like things are getting better at this point," says Dr. Kevin Hill, director of addiction psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. "We are working just as hard as before and we really don't have a safety net."

Hill says the city, state and nation need to make medication-assisted treatment much more widely available and work to reduce the negative feelings many addiction patients have about using drugs to control their drug addiction.

Dr. Marc LaRochelle, a clinician investigator at Boston Medical Center's Grayken Center for Addiction, says we just don't know right now if the epidemic is slowing or still heading toward a peak.

"Even with our advanced surveillance, it takes time to tell what a trend really is, especially if there's a particularly potent strain of an opioid that infiltrates the supply," LaRochelle says.

LaRochelle, who practices addiction medicine, says fentanyl analogs are changing so fast that doctors don't even have tests that can tell them what patients have taken and detect trends.

On the streets of Boston, Hooley says EMS crews are optimistic.

"We wouldn't be in this business if we weren't," Hooley says, "but I still think it's going to be a long siege before we can claim victory."

Hooley has a simple suggestion for anyone who's wondering what they can do: Find someone who's struggling with addiction and take them or their family a meal, just like you might do for someone recovering from cancer or another serious illness.

This article was originally published on January 11, 2018.

This segment aired on January 12, 2018.