Advertisement

BioBoom

Affording Miracles: As Biotech Victories In Gene Therapy Excite, Costs Spur Quest For New Ways To Pay

Resume

This spring, Dr. Jason Comander of Massachusetts Eye and Ear injected three drops of a precious fluid into each of Jack Hogan’s eyes. It contained billions of copies of a gene Jack needs for his eyes to convert light into sight.

At that moment the New Jersey 13-year-old became the first American to get a newly approved treatment that’s being touted as the first “true” gene therapy -- one that reverses an inborn genetic defect by giving patients the gene they need.

Jack has never seen much in dim light, and he faced the certain prospect of going totally blind in his 20s.

Then, one evening 27 days after the gene injection, Jack got the thrill of his life.

“It was like 7:30,” he recalled. “It was a little dim out. And that’s normally when I go in. And so I went to get pizza with my friend. And I left from the pizza place around 8:30, 9. And it was pitch-black out. And I rode my bike home all by myself. Like, I’ve never rode my bike at all at night. And now I can. I’m gonna … I’m gonna go so fast! I feel like a new kid!”

Jack is not cured of his eye disease, and his vision will never be perfect. But now he can see three times better in dim light than before. In daylight, he can see for the first time what his teacher writes on the whiteboard.

“It’s like turning on a switch metabolically. It’s amazing,” Comander said. “It’s really going to make a big difference in his life.”

That’s the kind of therapeutic home run scientists have dreamed about for decades. The promise of many such victories is fueling a boom in biotechnology, attracting billions of investment dollars to what many experts say is its epicenter in the Boston area.

Biotech entrepreneurs talk confidently about conquering a long list of genetic disorders, from blood cancers and immune deficiencies to hemophilia and sickle-cell disease. Someday, they say, maybe they'll notch even major disorders, like diabetes and Alzheimer’s.

The Payment Conundrum

But a big problem looms over the "BioBoom." How will these miraculous new gene-based treatments be paid for? Steam is building behind efforts to devise radical new ways to price and pay for the expected cornucopia of new-age therapies.

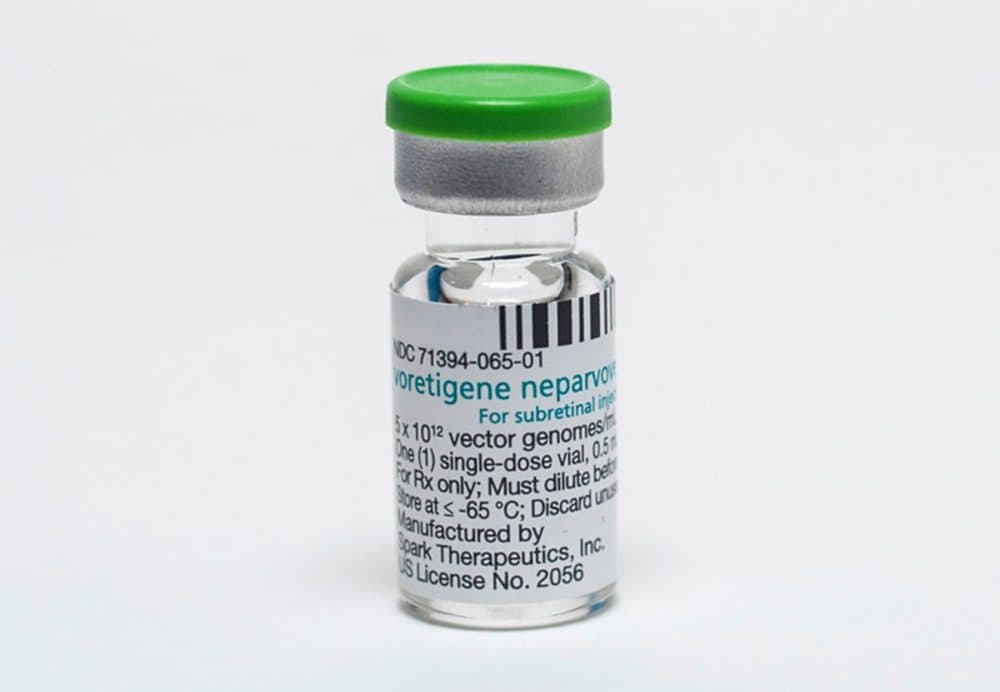

The treatment that restored Jack Hogan’s eyesight, called Luxturna, costs $850,000. That’s an incredible $142,000 per drop -- just for the drug alone.

Dr. Peter Bach, who runs the Drug Pricing Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, put that price tag in perspective. “If you treat one person with Luxturna," he said, "you’ve spent as much money that year as you have spent covering 32 families of four with commercial insurance."

Suddenly, million-dollar treatments are becoming the new norm. As more come to market, the cumulative impact threatens to overwhelm the budgets of insurers and government health programs.

“As these prices increase, the boom could very well create the conditions for its own undoing by prompting social and political action,” said Robin Scheffler, a historian of biology at MIT.

Sticker shock is giving new urgency to an old question: Just how do pharmaceutical companies set the prices of their products?

How Much Is Sight Worth?

How did Spark Therapeutics price Luxturna?

“We ultimately tried to answer the question of what is the value of sight in a young child who has a substantial portion of their life in front of them,” Jeff Marrazzo, the company's CEO, said.

Spark Therapeutics figured in the lifetime earnings patients would lose if they didn’t get the treatment. They also looked at how courts have compensated plaintiffs who’ve lost their sight.

"When you look over an entire lifetime,” Marrazzo said, “the value of sight is worth more than a million dollars."

But the company wanted to avoid the optics of a million-dollar price tag.

"We heard concerns from patients about access and from payers about budgetary impact. But we also had to consider what price would allow us to work and reinvest in other gene therapies that could help patients with other diseases."

Jeff Marrazzo, CEO of Spark Therapeutics

“We heard concerns from patients about access and from payers about budgetary impact,” Marrazzo said. “But we also had to consider what price would allow us to work and reinvest in other gene therapies that could help patients with other diseases.” (The company is working on a gene therapy for hemophilia, which afflicts about 20,000 Americans.)

In the end, Spark decided $850,000 per treatment would be enough. So far, more than half the private insurers it has approached have agreed to pay it. The company is in discussions with the federal government about securing Medicaid reimbursement, which the company figures about half the Luxturna patients will need.

Some point out that genetic disorders like Jack Hogan’s are so rare -- about 2,000 Americans are thought to suffer from his type -- that even prices like $850,000 per treatment will be a drop in the ocean of our $3.5 trillion health system.

Aligning Price With Patient Benefit

But it’s the sum total of all the million-dollar miracle treatments that’s worrying many in biotech and beyond.

One of them is Robert Coughlin, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council.

“My opinion is that if our industry doesn’t change our behavior, somebody in government is going to be forced to do it for us," he warned. "And as a former person who sat in government, you can’t expect anyone that’s an elected official to have the experience and knowledge to fix this the right way. It’s too complicated.”

One proposed fix tries to align the price of new drugs with the benefits that patients get, but in a more sophisticated way than Spark did with Luxturna. It’s called value-based pricing.

The movement is led by a Boston-based nonprofit called the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, or ICER, which considers itself a watchdog over drug pricing.

ICER uses a complex method to calculate how many years of high-quality life a particular treatment will provide. To be considered affordable, ICER says, a treatment generally shouldn’t cost more than $150,000 for each of those high-quality years. (Modest exceptions can be made for “ultra-rare” conditions where the cost can’t be spread over a larger population.)

"My opinion is that if our industry doesn’t change our behavior, somebody in government is going to be forced to do it for us."

Robert Coughlin, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council

When ICER put Luxturna through this analysis, their verdict on its worth was very different from the company’s.

“We estimated that, trying to capture all of the beneficial effects, you would still need to have the price come down about 50 percent, to somewhere around $400,000,” Dr. Steven Pearson, ICER’s president, said.

Not surprisingly, Spark’s Marrazzo disagrees. “I just don’t actually believe they captured the true quality-of-life impact on a patient,” he said.

We Can't 'Pay Any Price'

But Pearson insists there have to be price limits, even for patients with rare conditions like Jack Hogan.

“As exciting as a treatment like Luxturna is, and as small as the patient population is, we might think we can pay almost any price, but we can’t,” Pearson said. “Because there will be a growing number of treatments like this. And we have to create a system that is ultimately affordable and sustainable.”

ICER’s brand of rigorous price-setting is a radical departure. Pharmaceutical companies have always priced their products at whatever they think the market will bear. The U.S. market has fewer breaks on drug prices than any other country. And companies have never had to explain why a particular drug costs what it does.

Also, traditional drug companies like to market drugs that people have to take every day, so their price can be lower, whereas today’s biotech innovators aim to create one-and-done products like Luxturna. (It remains to be seen how long Luxturna’s benefits will last, but some study subjects have stable vision as long as four years after treatment.)

Marrazzo speaks for many in the industry when he calls for a fundamental change in the way new gene-based therapies are paid for. He says big upfront costs for these products are justified by avoidance of downstream costs such as hospital stays, specialty care and endless prescriptions.

“The aspiration should be better health for patients, not manufacturers getting paid for more, more, more – interventions, pills, whatever it is,” Marrazzo said.

Mortgaging Medicine?

But even rigorous value-based pricing won’t solve the affordability problem. That’s because everybody assumes most new innovative therapies will still carry eye-popping price tags, such as the half-million dollars ICER thinks Luxturna is worth.

In Jack Hogan’s case, his parents don’t have to pay for the drug. That was all worked out between their health insurer and Spark Therapeutics. (Spark declined to say whether it negotiated a discount from the $850,000 sticker price.)

But Jack’s mom, Jeanette Hogan, said that, when it comes to her son, the cost didn’t matter.

“I really didn’t care,” she said. “If I had to be billed for it, I have to be billed for it. And listen, if I had to pay $50 a month for the rest of my life, I’d do it. I’d find a way.”

If the Hogans had to pay for Jack’s treatment, they’d need to shell out more like $2,400 a month for 30 years -- pretty much like buying a house. In fact, Jeanette Hogan is hitting on an idea that the biotech industry is taking very seriously: Maybe insurers and government programs should pay for pricey new treatment over years, like a mortgage.

“What we’re working on,” Marrazzo said, “is a concept where payments could be made over time, as long as the therapy continues to show benefit in the patient.”

“This is nonsense,” said Bach, the drug pricing expert. He thinks mortgaging drugs would just encourage more astronomical prices.

Mortgages are inflationary, he said. “You pay considerably more today if you’re going to spread out the cost. That’s why people can buy homes, of course, that are way more than their annual income.”

Nevertheless, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, one of Massachusetts’ largest health insurers, is trying to figure out how it could pay off some drugs over three to 10 years after a substantial down payment.

Playing The Rationing Card?

That’s tricky in a system where patients frequently bounce around from one insurer to another. But Harvard Pilgrim’s medical director, Dr. Michael Sherman, said insurers may ultimately have no choice.

“Quite candidly, we have been unwilling to play the card that if the drugs are too expensive, we’re going to keep them away from our members whom we know need them,” Sherman said.

In other words, no insurer wants to say: “No, you can’t have that miraculous new drug.”

One alternative to such painful rationing is for government to set drug prices, as other countries do -- the very thing that the Mass. Biotech Council President Coughlin warned about. Biotech leaders fear that would stifle innovation.

To avoid either rationing or top-down price controls, it appears the wizards of the BioBoom will need to get as creative about paying for miracles as they are about inventing them.

This segment aired on June 7, 2018.