Advertisement

Commentary

Mass. Should Make It Easier For Moms To Get IUDs Right After Giving Birth

In 2010, nearly half of all pregnancies in Massachusetts were unintended. Many occurred soon after giving birth.

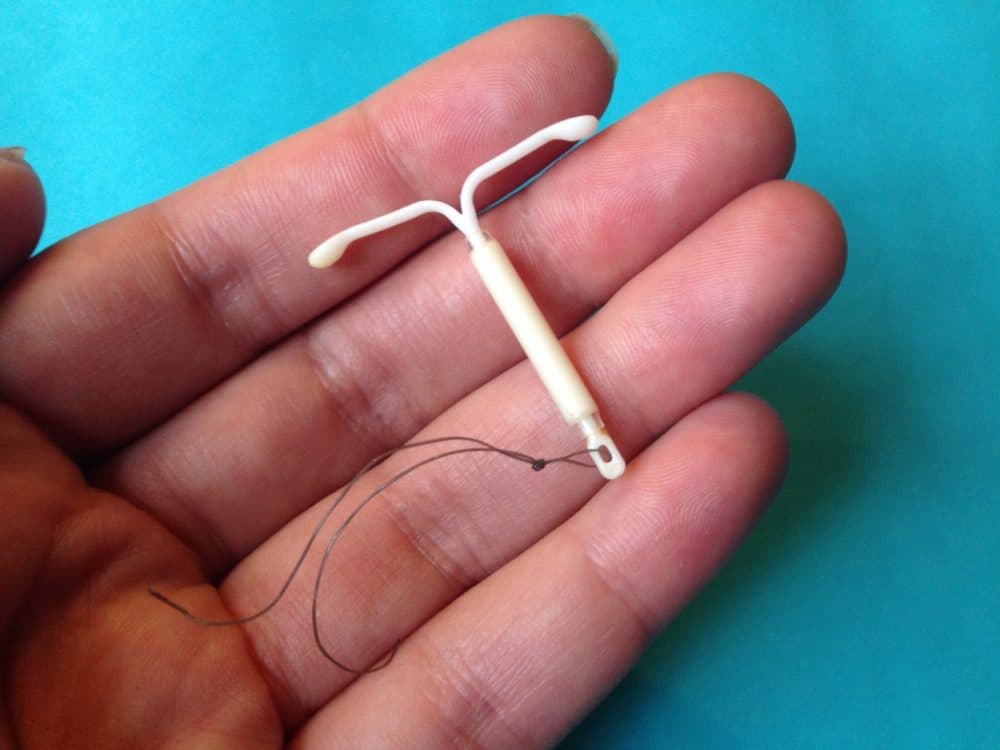

Long-acting reversible contraceptives — an intrauterine device, or IUD, and a rod-shaped implant in the arm — are the clearest way to reduce such pregnancies. Failing less than 1 percent of the time, they are the most effective form of reversible birth control available. They last between three and 10 years and require no maintenance.

Despite their clear benefits, such contraceptives are not often placed at the most obvious time -- in the minutes following delivery — even though that has been shown to be a safe and effective strategy for averting unwanted pregnancies. It’s also convenient, since women are already in the hospital getting care, and low-income women are more likely to be insured than they would be at other times.

States like South Carolina have realized the success of postpartum birth control placement and have made statewide changes to lower barriers for their implantation. The Massachusetts Legislature has considered similar action, but sent bill S.507, An Act Relative to Women’s Health, to study.

The bill would improve reimbursements for long-acting contraception not just in Medicaid but also among private insurance plans, ensuring fair coverage across all carriers.

Why Unbundle?

Providers receive a lump sum known as a bundled payment for labor and delivery services, which does not include insertion of this type of birth control. The IUD and implants cost between $400 and $1,000. As a result, providers may lose money by offering them, because that cost is not included in the "bundle."

Hospitals are also not keen on the high upfront costs and the difficulties of maintaining IUD and implant inventory, even if Medicaid dollars will eventually come through.

This stems from the complicated coverage for long-acting contraceptives. If they are considered a medical benefit, the provider bears all of the initial cost, which often leads to doctors maintaining low supplies of IUDs and implants because of the high upfront costs of buying these devices and the uncertainty of when they will be used. If the contraception is instead charged as a pharmacy benefit, the cost is split between the insurer and the provider. That removes the upfront costs for the provider, but means that providers are effectively unable to offer same-day placement since a patient would have to see the provider twice -- once for the prescription and another visit for the procedure after the pharmacy or distributor bills the insurer.

The Massachusetts Legislature has the opportunity to determine what type of benefit long-acting reversible contraceptives are. By removing the confusion and high overhead costs, they also have the opportunity to increase their usage among Massachusetts residents.

With federal backing, many states have already taken the crucial step of unbundling Medicaid payments for postpartum contraceptives. South Carolina, which in 2011 had the highest teen pregnancy rate in the country, made the switch in 2012. Not only did the state unbundle services, it also took the extra step to help in the outpatient setting by eliminating administrative hurdles like prior authorization.

The state saw postpartum in-hospital IUD and implant insertions increase from 10.5 percent to 14.2 percent of women covered by Medicaid between 2013 and 2015, saving the state’s Medicaid agency $1.7 million by preventing unintended births. After Colorado made the change, it recovered its investment more than six times over in just three years.

Timing Matters

One study found that immediate placement of postpartum IUDs can prevent an additional 88 unintended pregnancies over two years per 1,000 women when compared to placement at routine visits.

This postpartum strategy has been supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid gave its blessing in 2016, urging states to adopt the practice.

Yet mothers seeking postpartum placement are often told to return in six weeks to get their IUD or implant. Those weeks after childbirth can be an intense and busy time, and women who are told to return are less likely to end up having long-term contraception placed than those women who receive the devices immediately after delivery.

Furthermore, half of those women resume sexual activity before their six week follow-up. This delay in care and failure of follow-up puts women at high risk of rapid repeat pregnancy.

Another barrier to postpartum placement is practitioners’ misconceptions about the effectiveness of implanting so soon after birth. Some believe that with the changes in the cervix during labor, an IUD placed in the immediate period after birth would just be expulsed. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists notes that this is true, with rates possibly as high as 10 to 27 percent, depending on the study.

Nevertheless, that risk is outweighed when considering the birth control's cost-effectiveness and the number of women who schedule, but don’t return for their six-week follow-up visit. Some health care professionals may also be concerned about the theoretical risk of hormonal IUDs interrupting the physiological changes required for breastfeeding. The evidence, however, shows that IUDs do not negatively affect actual breastfeeding outcomes.

In addition to education about postpartum birth control, there must be more training for health-care workers. Providers in Massachusetts have been found to have low rates of knowledge of postpartum IUD placement. With the changes in the size and shape of the uterus in pregnancy and the shortening of the cervix during labor, inserting an IUD after delivery imposes technical challenges for the physician. Doctors often require formal training and more experience with instrumentation and visualizing placement. The Senate bill calls for a much-needed training program for clinicians.

It is time that Massachusetts caught up with other states in maternal care. South Carolina, Colorado and others have shown that implanting long-acting reversible contraception in the moments after birth can reduce unintended pregnancies and recoup savings for states in a short period of time.

With the passage of the ACCESS Act last year, which ensures access to no-cost birth control in Massachusetts, the Legislature signaled that women’s health is a bipartisan issue that can bring together uncommon allies. This latest bill deserves the same treatment.

Raj Reddy is an MD/MPH candidate at the Tufts University School of Medicine.