Advertisement

Thyroid Cancer Treatment: Less Is Often More, But Surgeons Are Slow To Shift

Resume

Ten years ago, Carol DiFelice got a weird feeling in her neck.

"Most people do not feel it," says DiFelice, a registered nurse from Groveland, Massachusetts. "Mine was not that big. It was just that — a sensation — I can't even describe it. It was a really subtle sort of sensation."

It was a tumor almost the size of a peanut. DiFelice had her entire thyroid removed, and took radioactive iodine to kill off any possible remaining cancer cells in the area.

These days, she's a volunteer with ThyCa, the Thyroid Cancer Survivors' Association, and thinks if she'd been diagnosed today, she might have been able to have just half her thyroid — just one wing of the organ's butterfly shape — removed, in a procedure called a lobectomy. It's less risky than a full thyroid removal, and less likely to leave patients needing hormone replacement pills for the rest of their lives.

"That is why they're talking about it more," DiFelice says. "When mine was done, and for the past almost 10 years or so, they were recommending total thyroidectomy, that was kind of the standard for any thyroid cancer."

But the standard changed. In 2015, the American Thyroid Association put out new recommendations for scaling back treatment of low-risk tumors, says association president Dr. Elizabeth Pearce, a professor at the Boston University School of Medicine.

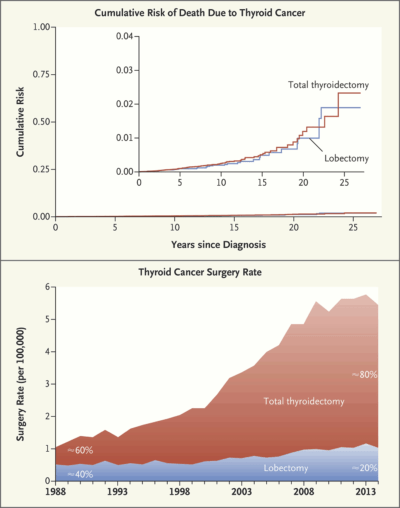

"One would expect, then, since that publication, that lobectomies should be increasing and total thyroidectomies should be decreasing in this country, and we're not seeing that," she says. In fact, total thyroid removals have risen far more than lobectomies.

"So that suggests either people don't know the guidelines, or it's just really hard to change people's minds when they've learned to practice one way and not another," Pearce says.

It may be hard, but Dr. Jerry Doherty, the chief of surgery at Brigham and Women's Hospital, is trying. He co-wrote a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine pointing out that whether a patient gets the full thyroid removed or only half, the risk of death from thyroid cancer over the 25 years after diagnosis is only 2 percent.

Yet, even though more and more of the cancers detected are nonthreatening, the vast majority of patients with small cancers are still getting full thyroid removal.

"We should have seen smaller operations, more observation instead of operations," Doherty says. "And in fact, what we saw is an increasing proportion of patients who were subjected to the most thorough treatment of total thyroidectomy, that carries some complications that the less intensive operation doesn't."

Those risks include potential damage to the nerves that help control swallowing and speech, and to glands called the parathyroids — which could mean the patient forever after needs to take multiple daily doses of calcium.

"We should have seen smaller operations, more observation instead of operations."

Dr. Jerry Doherty, chief of surgery at Brigham and Women's Hospital

In the operating room recently, Doherty narrated as he explored a patient's thyroid and went ahead with removing just half, as recorded by Brigham and Women's: "This is the tumor here — nicely fully contained within the thyroid lobe," he says.

"The rest of the thyroid lobe has some little nodules in it but nothing very concerning," he muses. "Good. So we've oversewn the right lobe of the thyroid gland, leaving that side of the thyroid gland, the nerve on that side, and the parathyroid on that side all untouched."

Untouched — and undamaged. Doherty very roughly estimates that more than half of thyroid cancer patients are being overtreated, and he sees "low-volume surgeons" — surgeons who rarely operate on thyroids and may not be up to date on the recommendations to scale back — as a major cause.

"And so patients who see these very good physicians, who just do this as a small part of their practice, don't get the same quality of care," he says.

Dr. Pearce, from the American Thyroid Association, agrees: "I think selecting a high-volume surgeon is probably a good starting point for anybody who has been told they need thyroid surgery," she says.

Another starting point is the awareness that "less is more" when it comes to certain cancers. Doherty's co-author in the New England Journal paper, epidemiologist H. Gilbert Welch, is a leading thinker on the problem that as patients are screened more for cancer, more tumors that never would have caused problems are detected.

So often the treatment — or rather, the overtreatment — can be worse than the disease ever would have been, Welch has long argued. That's true in breast and prostate cancer — and, it seems, in thyroid cancer as well.

Forty-one-year-old Amal Sarri from Everett says she's grateful she had the option of "less." She was already dealing with another type of cancer — an aggressive sarcoma treated with chemotherapy, radiation and surgery on her hip — when a scan turned up cancer in one lobe of her thyroid. Dr. Doherty removed half her thyroid this summer and left a barely visible scar on the front of her neck. Her "rock star" hoarseness passed in a day or two.

"It was a very simple thing, compared to the hip surgery, compared to the chemo, radiation," she says. "The thyroid surgery was one of the easiest ones."

Of course, every tumor is different; some need aggressive treatment. And some patients have trouble doing "less" with cancer — they want maximal treatment.

But South Korea offers perhaps the ultimate cautionary tale on thyroid cancer: More than 15 years ago, it ramped up mass screening for thyroid cancer (which is not recommended here in the United States.) The country's rate of detected thyroid cancer shot through the roof, Dr. Pearce says.

"And they have since stopped doing that global screening," she says, "because they were finding enormous numbers of very small cancers, performing huge numbers of surgeries which probably were not warranted."

How do they know? Because the South Korean thyroid cancer death rate remained just about the same.

This segment aired on November 13, 2018.