Advertisement

As Deaths Rise, The Urgent Search For Medications To Treat Meth

ResumeOverdose deaths tied to opioids are down slightly in Massachusetts and across the nation as a whole. But deaths involving stimulants, cocaine and methamphetamine, are way up.

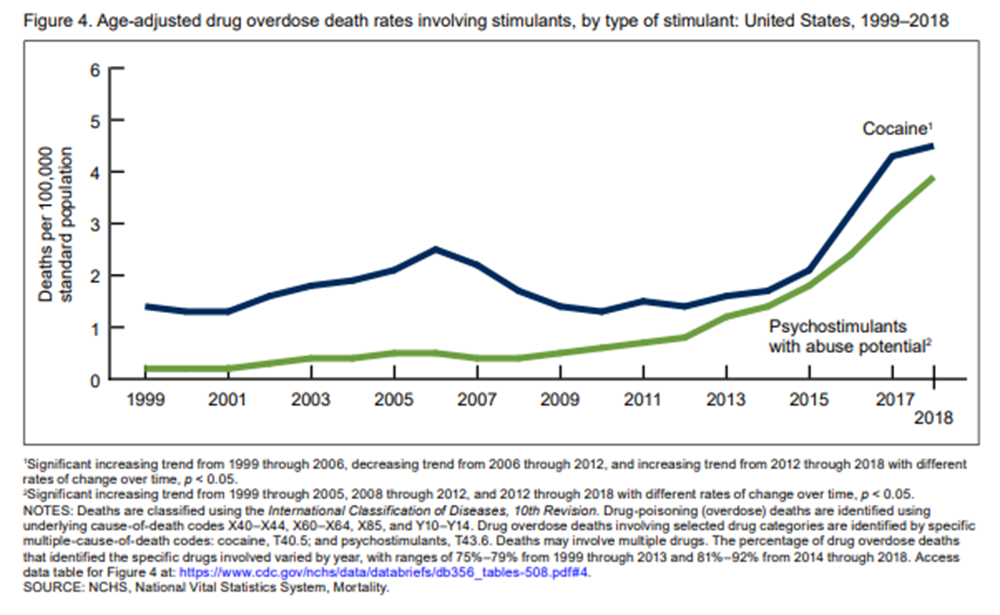

The Centers for Disease Control says fatal cocaine related overdoses increased 27% a year, on average, between 2012 and 2018. Deaths linked to psychostimulants including meth rose 30% during the same period, a nearly five-fold increase. Many drugs users inject both opioids and stimulants.

Public health leaders say these numbers confirm an urgent need for medicine to complement counseling and peer support for drug users addicted to stimulants. Unlike with opioids, there are no approved treatment medications and no equivalent of naloxone to reverse a toxic meth high and avoid a heart attack, stroke or life-threatening rise in body temperature.

Patients say they often hit another barrier: licensed detox programs that are supposed to accept all types of addiction patients, but aren’t prepared for those addicted to meth.

“So a lot of people have to lie to get in,” says Eric, a 32-year-old from Boston. We’re only using his first name because Eric has a history with illegal drugs.

Sometimes Eric would say he needed to detox from alcohol. Other drug users say they take an opioid so it will show up in a urine test. Some detox providers say they don’t admit patients on meth or cocaine because they don’t have an acute medical need. The crash after a meth high is more likely to be deep sleep as compared to the severe nausea, tremors and headaches that opioid users experience.

Once inside a detox unit, Eric would talk his way into a two- or three-month residential program or a spot in a sober home.

“They don’t really work on specifically meth addiction,” he says. “But the only thing that is good about it, it’s an environment where I’m away from wherever I was using and around other people that hopefully want to get clean.”

Some meth and cocaine users have used abstinence programs to cope with addictions for years. The Matrix Model is one widely recognized option. But as meth becomes more potent, people who use it say the addiction is harder and harder to fight.

After a few months in an abstinence-based program, Eric would be back on the streets, looking for housing and a job. He’d sink into a depression and use meth to get himself out. After 10 or so rounds of detox, more rehab programs and months in sober homes, Eric is managing his addiction to heroin with counseling and buprenorphine.

Fighting the powerful urge to shoot meth is more difficult.

“I was able to stop everything,” Eric says, “literally, marijuana, alcohol — everything except for meth.”

Eric’s physician, Dr. Laura Kehoe, says more and more meth patients who can’t get themselves away from meth approach her with what Kehoe calls a shocking request.

“We’re seeing people coming in, in desperation, asking to be essentially locked up,” Kehoe says, “to be locked away from the substance.”

She declines their requests.

“We know that is not an effective strategy and is not a therapeutic intervention at all,” Kehoe says.

Instead, Kehoe says she books more frequent appointments with these patients at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Bridge Clinic: building relationships, using medicines to ease their anxiety or depression, connecting them to group counseling, social workers and peer recovery coaches.

“We're all working together, trying to come up with creative and innovative ways as we wait for science to catch up," Kehoe says.

Much of that catch up is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, where Dr. Nora Volkow is the director. She says finding ways to treat a meth or cocaine addiction must be a top priority as the death rate climbs.

“It’s very problematic,” Volkow says. “It’s rising very rapidly, and we’re far behind than from opioids.”

She lays out the range of research for drugs to treat both the acute, overdose episodes and chronic treatment. To prevent an overdose, she says the U.S. government is funding trials of a drug that could be injected into someone dangerously high on meth.

“One of the most promising areas is antibodies that can trap methamphetamine so that it no longer has pharmacological effects,” she says.

Intervexion, the company running these trials, says it expects final results in mid-2020. Volkow says these antibodies could become a treatment option if they linger in the body long enough to block continued meth use.

To treat a meth addiction, Volkow explains the most proven method is something called contingency management, where drug users are rewarded with food vouchers or movie passes when their urine is drug-free.

“That is the only strong evidence for methamphetamine,” she says.” It does not mean other interventions may not be useful, the evidence is not there.”

The evidence is weak, for example, says Volkow, around the idea of using milder stimulants to replace meth. Some doctors transition patients from meth to a prescribed stimulant, such as Adderall, Vyvanse or Ritalin, and then wean patients off those drugs.

There’s emerging evidence that some antidepressants may help reduce meth use. Researchers are testing naltrexone and buprenorphine — two drugs used to treat an opioid use disorder — to see if receptors they block can limit cravings for meth. And there’s work on a possible meth vaccine.

Volkow says study results have been hampered by the FDA requirement that potential treatments produce abstinence. That requirement is under review. If the FDA approves meth treatment drugs based on a pattern of reduced meth use, Volkow says some drugs that did not receive earlier approval may warrant a second look. She says it will be important to include more women in future studies about meth treatment.

While he waits for approved medications, Eric has put together his own treatment package. One physician prescribes him gabapentin because Eric says this pain and seizure med improves his motivation and energy. Kehoe has prescribed Wellbutrin for depression.

Eric adjusts the doses, sometimes daily, as needed. This ad hoc combination, along with counseling, works for Eric. He has a job, his own apartment, is back in touch with a cherished aunt and hasn’t used meth since September.

“I’m a lot better,” Eric tells Kehoe, with a shaky laugh.

She grins. “Your positivity is contagious.”

This article was originally published on January 31, 2020.

This segment aired on January 30, 2020.