Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

One Coronavirus Problem Solved (Almost): Testing Swabs Are On The Way

Resume

Here’s something you probably don’t want to think about: The best way to get a good coronavirus sample is to push a long, thin stick with a rough tip through your nose, into your nasal cavity, and twirl it around a few times.

"What they tell us in medical school is if the patient isn't complaining, then you're not doing it right," says Ramy Arnaout, associate director of clinical microbiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

For the last few weeks he’s been studying swabs. Specifically, he's been trying to figure out how to get more of them into the field quickly.

The need is critical. Getting the coronavirus under control will require widespread testing, as soon as possible.

"We’ve been doing a lot of testing," Gov. Charlie Baker said this week, "but if you were to say to any of us up here, ‘are we doing enough testing?’ we would say ‘no.’ ” And if you talked to most other states they would say the same thing.”

One major testing bottleneck has been a lack of swabs; in particular, the long, rough-tipped ones known as nasopharyngeal, or "NP" swabs. There aren’t enough to meet the huge demand, and that’s slowing down testing. Nasopharyngeal aren't included in the Strategic National Stockpile, and James Kirby, Beth Israel’s medical director of clinical microbiology, says the usual suppliers can’t meet this years' extreme demand.

"In a typical year, we might do 1,500 influenza tests, and now we're talking about doing that many COVID tests in a single day," says Kirby. "The capacity wasn’t there."

So Kirby's colleague, Arnaout, started getting creative. He and his team started scrounging around, asking colleagues for swab donations, repurposing other types of swabs.

But "even after all the scrounging we did, and all of the repurposing we were able to do, we really only bought ourselves another couple of weeks of swabs," Aranout says. "This pandemic is gonna take a lot longer than that."

"What they tell us in medical school is if the patient isn't complaining, then you're not doing it right."

Dr. Ramy Arnaout

Arnaout says he realized that the best way to get a supply of swabs was to figure out how to make them. This isn't as simple as it might seem.

Testers need sterile, medical-grade swabs that can be mass produced quickly, properly collect a sample, and not break off inside someone’s head. Something simple like a drugstore cotton swab wouldn't work, because cotton inhibits the chemical reaction used to test for the virus. And Arnaout wanted to work with manufacturers who were "shovel-ready" — already cleared by the Food and Drug Administrations to make devices like these.

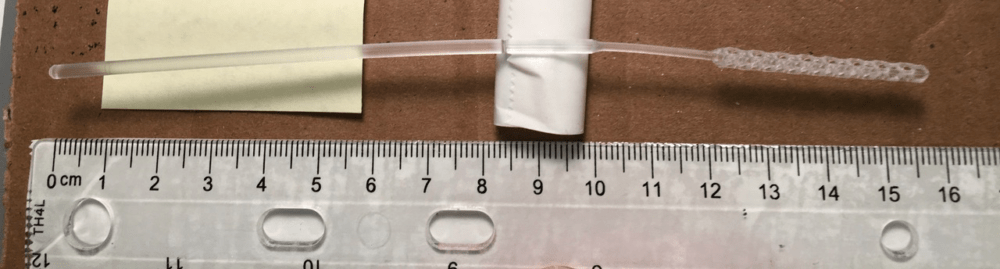

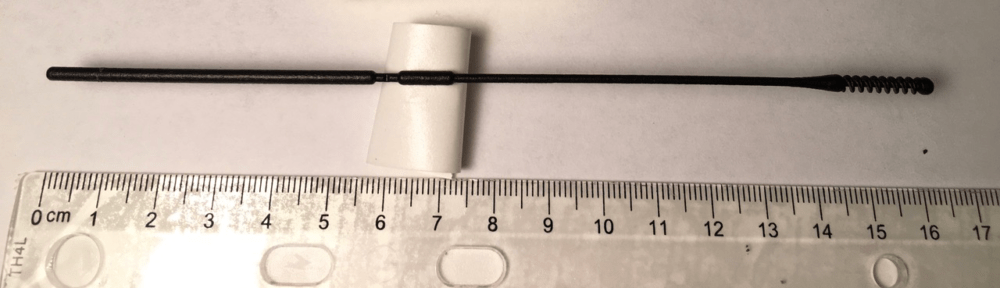

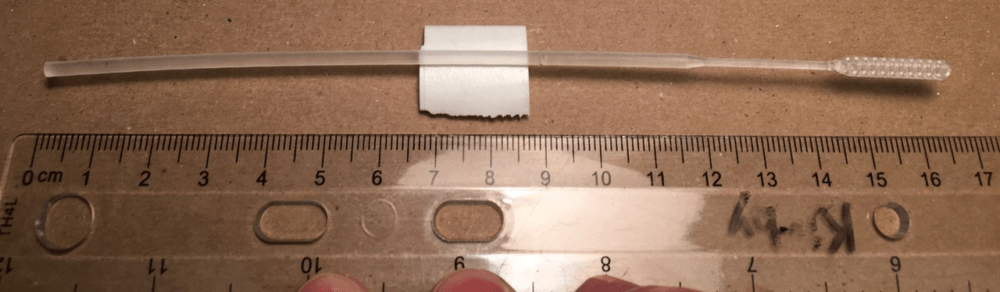

So Arnaout put out a call for prototypes, and soon his lab was flooded with samples. The swabs had tips in an astonishing variety of shapes: springs, spirals, honey drippers, cattails.

"This is academics, individuals, manufacturers, health care workers across the country, all pitching together for no obvious personal gain," he says. "And so our lab just became a factory for putting swabs through their paces.

He and his team have tried the most promising ones on patients already getting tests for the coronavirus.

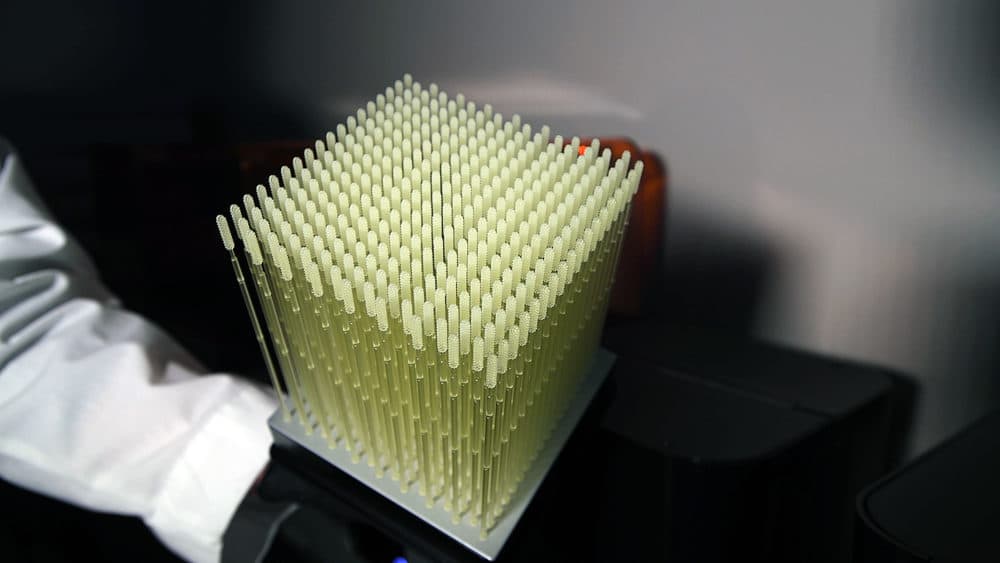

At the same time, other entrepreneurs are trying the same thing. The Somerville-based 3D-printing company Formlabs has worked with physicians to come up with their own design, which they’ve just started printing in their Ohio factory. They hope to reach a peak capacity of 100,000 swabs a day and are shipping their first batch today: 15,000 swabs to Ohio State University.

Formlabs chief product officer Dávid Lakatos says 3D-printing is certainly not the most cost-effective way to mass produce swabs. But the company isn't looking to make a profit off its new product.

"We are doing this at cost, and we’re going to do it until we need to," Lakatos says.

He says that while he's happy his company can make a contribution during the crisis, he's hoping that traditional swab manufacturers will eventually catch up with demand.

"We have not found a new niche for our business where we need to be printing swabs until the end of time," he says.

Some of the designs tested at Beth Israel are also heading into production soon.

"I am extremely hopeful that the swab limitation will not be an issue in the weeks ahead," says Beth Israel's Kirby. "That will allow us to open up testing to a much larger group of patients."

This article was originally published on April 17, 2020.

This segment aired on April 17, 2020.