Advertisement

Closing Pilgrim

Pilgrim Is Closing. So Then What Happens To The Radioactive Waste?

Resume

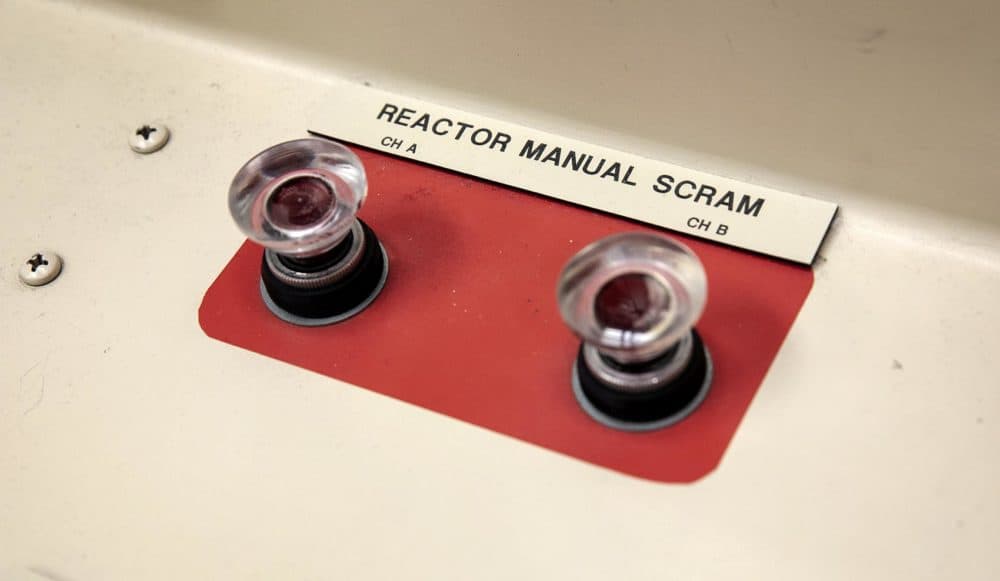

This week, Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station will power down for the last time.

Over the next few years, workers will move the radioactive fuel into storage, dismantle the plant, and clean up the site. The process is called decommissioning, and a lot of people are worried about safety, cost and where the nuclear waste will finally end up.

The biggest source of radioactivity at Pilgrim is the plant's fuel assemblies, which power the reactor. Entergy, the company that owns Pilgrim, says there are 580 fuel assemblies currently in the reactor, and another 2,378 used assemblies cooling off in the blue water of the plant's spent fuel pool. That's in addition to 1,156 stored outside the plant in huge containers.

All together, there are 4,114 fuel assemblies at Pilgrim. They’ll stay radioactive for thousands of years. And with nowhere to put them — for now, at least — they’ll stay in Plymouth indefinitely.

“With no repository in sight, Plymouth — America’s hometown — will be a nuclear waste dump,” says Diane Turco, executive director of the watchdog group Cape Downwinders. “No one knows what to do with this waste. ... So I think we need to prepare that it’s going to be in Plymouth for a long time."

Storing The Nuclear Waste

After the plant powers down, workers will move the fuel from the reactor into the spent fuel pool. It will take a few years for the fuel to cool off enough for workers to move it from the pool into steel canisters. Then they'll put the canisters into enormous steel-and-concrete containers called “dry casks” for storage.

Everybody wants the job done right, because an accident could release radioactive material into the environment. The worst-case scenario — a major fire in the spent fuel pool — could put thousands of lives at risk.

“Decommissioning is a very dangerous time at Pilgrim. The spent fuel will be moved from the pool to the dry casks; the dry casks will be moved on the property,” says Turco. “To do it quick and fast doesn’t necessarily mean safe — let’s do it right.”

The fuel storage casks are made by New Jersey-based Holtec International. Holtec produces storage components for more than half of the nuclear power plants in the United States. And with nuclear plants shutting down across the country, business is booming.

“At a time when nuclear energy is taking a downturn, we’re really expanding,” says Joy Russell, Holtec's senior vice president of business development and communications.

Each dry cask that will store the spent fuel at Pilgrim looks like a giant soup can: about 20 feet tall and 11 feet in diameter. Inside, the casks have inner and outer steel shells separated by more than 2 feet of concrete for shielding. When filled, a single cask can weigh up to 300,000 pounds, almost twice as much as a fully loaded 737 airplane.

It seems like a surprisingly low-tech way to hold highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel. That’s the beauty of it, says Allen Hickman, vice president of manufacturing for Holtec.

“What many people don’t realize is the amount of engineering, design and analysis that went into licensing this with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission,” says Hickman. “It had to go through all different kinds of scenarios: being knocked over, being struck by a projectile, a plane crashing into it, a seismic event.”

Hickman says all this gives him a lot of confidence in the casks: “I’d rather live next to a nuclear power plant storing our equipment,” he says, "than next to a fossil plant putting out sulfur in the air.”

Not everyone shares Hickman’s confidence, including Plymouth resident Sean Mullin, chair of the state's Nuclear Decommissioning Citizens Advisory Panel.

“What happens if a crack emerges? There is a lot of salt in the air, and there's a lot of other things that could deteriorate it,” says Mullin.

“I’d rather live next to a nuclear power plant storing our equipment than next to a fossil plant putting out sulfur in the air.”

Allen Hickman, of Holtec

At a public meeting in March, NRC Reactor Decommissioning Branch Chief Bruce Watson said the NRC is currently working with industry to develop surveillance and testing requirements, and that the storage facility at Pilgrim would be inspected "at least annually." If workers detect a serious leak or crack in a cask — an event the Watson called "extremely unlikely" — it will be "encapsulated" in another cask.

Mullin is skeptical of the encapsulation plan.

“There should be something better,” he says.

Decommissioning In 60 Years — Or 8?

Holtec wants to do more than build nuclear storage casks. The company plans to buy Pilgrim and handle the whole decommissioning process: move the fuel to storage, tear down the plant, and clean up the site. But Holtec has never fully decommissioned a nuclear plant before. And unlike Entergy, which proposes decommissioning the site in 60 years, Holtec says it can be done in eight.

“This is a new model that's come about within really the last several years. We have companies that want to do a soup-to-nuts kind of approach,” says NRC spokesman Neil Sheehan. “It obviously raises a lot of questions, but we're going to be diligent when it comes to looking at those.”

Holtec’s proposal worries critics like citizen’s group Pilgrim Watch and Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey. Both have filed petitions to intervene with the NRC.

“Holtec has never actually cleaned up a nuclear power plant before, and it's proposing to do so at what's really a record pace,” says Healey. “What we want is for the closure to be done safely. We want the site cleaned up and we need to make sure that there's enough money there to make that happen well.”

Holtec also wants to buy Indian Point nuclear plant in New York, and build an interim storage site in New Mexico, where the company hopes to eventually ship spent fuel from Pilgrim and other sites.

Critics say Holtec is stretched thin.

“We fear that they have bitten off far more than they can chew, negatively impacting the quality of oversight and attention to properly decommission Pilgrim Station,” wrote Pilgrim Watch director Mary Lampert in an email.

In April the NRC issued two safety violations against the company for an incident involving dry casks at the San Onofre nuclear plant in California. Although no radioactive material was released and the NRC did not issue a fine, Holtec’s Russell says the company takes the violations “very seriously” and is scrutinizing technology, training and procedures.

“This is an industry where we're proactive, and we make those changes that are necessary,” says Russell. “We do not like to be a reactive industry.”

“I think they're all learning, including the NRC,” says NDCAP chairman Mullin. “They're getting better at it. I think like any other process, you know, you do it five, six, eight times, you're a little better on the ninth than you were the first. I don't like the fact that Holtec is going to learn how to shave on our beard. And that's what's about to happen.”

Cost Concerns

If Holtec purchases Pilgrim, the company will receive the plant, the surrounding land and a decommissioning trust fund currently valued around $1 billion. Holtec might also get additional money by suing the federal Department of Energy for failing to build a permanent nuclear waste repository.

But an old plant like Pilgrim will likely have cleanup problems beyond nuclear waste, like asbestos and lead paint. And other nuclear plants, like Connecticut Yankee and Yankee Rowe, cost far more to clean up than expected.

“We think that Holtec is seriously underestimating what it's going to cost to get this done — underestimating to the tune of millions of dollars,” state AG Healey says. “And at the end of the day, if Holtec begins this project and doesn't have the money to finish it, it's going to be the state, our residents and taxpayers that are going to be on the hook, and we want to make sure that doesn't happen."

“We think that Holtec is seriously underestimating what it's going to cost to get this done."

Attorney General Maura Healey

Critics are also concerned about Holtec’s formation of a limited liability company with Canadian engineering and construction company SNC-Lavalin called Comprehensive Decommissioning International, which will handle Pilgrim’s decommissioning.

Dan Wolf, a former state senator from the Cape and Islands — and the founder and CEO of Cape Air — says the move insulates the parent company and makes it unclear who is ultimately financially responsible for the cleanup.

“My concern is, if there's not enough money and the job doesn’t get completed, it's going to fall both on our government and on the ratepayers to make up any deficiencies,” says Wolf. “It's one of the more egregious cases of socializing risk and privatizing profit.”

Holtec's Russell calls the company's cost estimate "conservative" and says that the NRC puts the company "on the hook" for the decommissioning.

"There's no way to pull up stakes and run away," she says.

NRC spokesman Sheehan concurs.

“Just because you've created an LLC does not mean that we would let somebody walk away without finishing the job,” he says.

He adds that the NRC will evaluate ongoing decommissioning costs and force the company to adjust — through the Department of Justice, if necessary.

"They need to complete the radiological cleanup of that site," Sheehan says. "They're going to live up to that obligation."

The Pilgrim site is already storing spent nuclear fuel in 17 dry casks near the reactor building. Eventually, there will be 61 casks, stored on a new pad, 75 feet above sea level, partly to safeguard against sea level rise. It's expected they’ll be moved there by 2021 and protected by armed guards.

While Congress has recently started talking about a new national repository for nuclear waste, and Holtec says it hopes to remove the spent fuel from Pilgrim by 2062, there's a chance that waste could remain at Pilgrim (or rather, the former Pilgrim) indefinitely, a silent monument to the nuclear age.

This segment aired on May 30, 2019.