Advertisement

Anna Deavere Smith 'Does Time' In The 'School-To-Prison Pipeline'

Resume

When you listen to Anna Deavere Smith, you don't just hear Anna Deavere Smith. The renowned playwright and actor builds her scripts from transcribed interviews with dozens of real people.

She first came to national attention with "Fires in the Mirror," about the racially divisive 1991 riots in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. She followed that up with "Twilight: Los Angeles," about the aftermath of the Rodney King beating in 1992. More recent works have touched on Hurricane Katrina, the U.S. health care system and much more.

Smith pioneered this genre, often called "documentary theater": plays built verbatim from the words of real people. One distinguishing feature of her plays is that all of them feature just one actor playing all the roles: Smith herself. (Television audiences may recognize her as Nancy McNally on "The West Wing" and Gloria Akalitus on "Nurse Jackie.")

Lately, Smith has talked with hundreds of people about what's called the school-to-prison pipeline — the path that can take a kid from a kindergarten suspension, through juvenile hall, to jail time. And she's turned their voices into her latest play, "Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education." It's at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge through Sept. 17.

Smith performed what she calls "an in-progress version" of the play in Berkeley, California, and in Baltimore, her hometown. She took a break from rehearsals at the A.R.T. before opening there to talk about how "Notes from the Field" evolved.

"I hadn't really paid much attention to what was going on in my hometown in terms of what I would call the death of Baltimore city," Smith said, "until some social-justice funders wanted to introduce me to this idea I'd never heard of before, the school-to-prison pipeline."

They brought together a group of educators to talk with Smith — a familiar group for her, because nearly all the women in her family were teachers. But this time she heard stories of young children suspended for minor infractions, of older students being pushed out of school and ending up in prison, of lives lost to violence, mental illness and drugs.

"And I thought, 'Oh my goodness, this is what I come from, and it's a disaster.'"

She found herself thinking of how much had changed since her mother was an educator in Baltimore.

"It’s very difficult now for a single person to make a difference," Smith said. "And that’s what my mother and all her friends did. She always had these big boys at our house, teaching them to read. And all I’d overhear — there was always some kid they were changing. And I think it’s really hard to do that now."

The reasons are complex, she said: the nation's growing gap between rich and poor, the ongoing segregation of schools by class and race, the lasting effects of childhood trauma and poverty, "the drug industry, which has taken hold of communities and young people ... and guns!" Smith exclaimed. "I never heard of anyone bringing a gun to school."

And the results are stark: Between 1979 and 2009, the rates of imprisonment for young men of color, especially those who drop out of school, soared.

"It’s not even fair to call it the school-to-prison pipeline," Smith said, "because we seem to be blaming teachers and schools for something that’s a pretty complex social problem."

So Smith decided to make a play about the subject, and she started talking to all kinds of people: teachers, students, cops, prisoners. Two hundred and fifty of them — so far — including a few in Boston, although this city, she said, could almost fill an entire play on its own, with "the history of busing and then the story of [Charles] Stuart, right, and against the background of a city that was abolitionist."

Out of those interviews, she built "Notes from the Field."

Smith plays all the characters. Her voice, her stance and her gestures shift in a flash to create a shy teenager ... or a renowned poet ... or an inmate or a judge. Her work goes beyond mere impersonation to fill the stage with a whole world of people. Even in the unpolished setting of a rehearsal room, her ability to shape-shift, to become these people in an instant, can build a scene of astonishing specificity.

You can get a taste of this in a video from her opening speech at a national theater conference in June, where she performed a bit of the play. (The excerpt from "Notes from the Field" begins around 47 minutes in.) One minute she's a young man in Baltimore who's had run-ins with the police; the next, she's James Baldwin.

Smith places the voices in counterpoint to one another, letting their stories collide and connect to create a kind of choral response. In other works, Smith has supplied all the voices herself. This time, she adds another voice. Well — not quite a voice. A jazz bass.

"We’re coming out of the black tradition of music, of the blues, of field hollers, blues shouts, and cries, and call and response," she said. A different kind of notes from the field, perhaps.

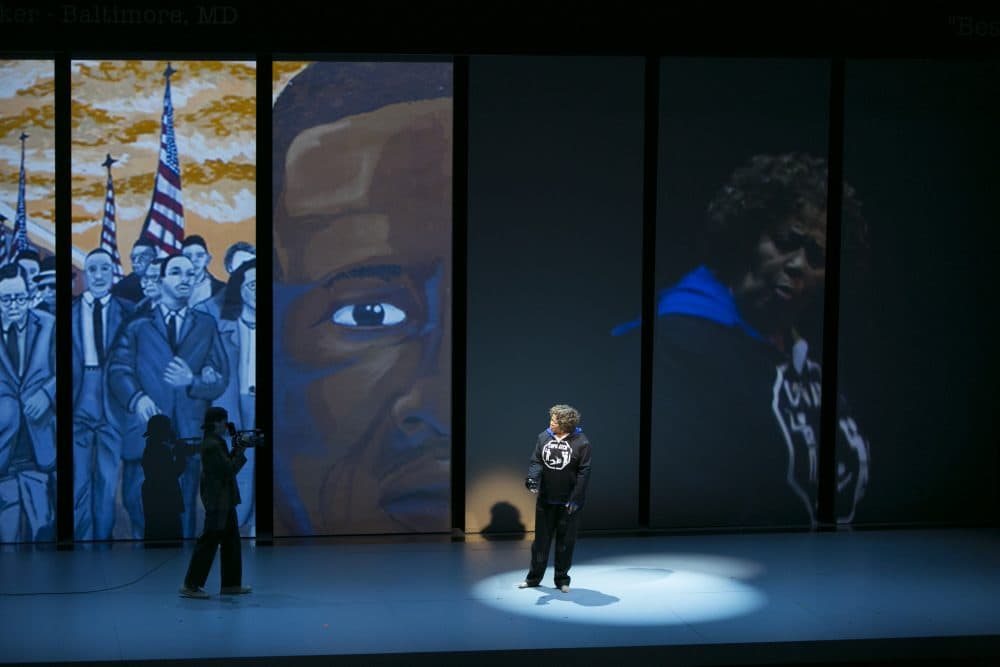

Call and response: It's an apt description of how the play works. One voice speaks, another answers. Smith's characters respond to one another, to video projections that add context, and to the music. Together, they build the story.

"She struggles to show every side of the picture, every side of the story," director Leonard Foglia said. "We talk about showing the facets, and not coming to conclusions, and having the audience do it."

Foglia has interwoven video projections and slides of data to provide context, he said: about the death of Freddy Gray in police custody in Baltimore, about Ferguson, about the disparate rates of suspension and expulsion for black and white students.

"I just want to make sure that the context is there," Foglia said. "It's sort of as if you're watching a very superficial news broadcast, and then you flip it around and then here are the real people — you know, what's really going on behind it."

As for the bass playing, it's supplied by Marcus Shelby, an acclaimed San Francisco musician who has worked with Smith before. He said both he and Smith found the call-and-response familiar from the religious traditions in which they grew up.

"Much like in the black church, where you just have this sort of back-and-forth between the minister and the people in the pulpit or in the choir, we kind of try to relive that or recreate that," Shelby said.

Shelby stands onstage with Smith. Sometimes he plays in response to something she says; sometimes he just listens.

"It’s self-expression, all right?" Shelby said. "It’s inflection, it’s call and response, it’s improvisational, and it’s personal. And it’s also used within the collective. And that’s how musicians use the blues."

Shelby says that approach goes beyond music.

"Because it’s your personal expression in this sort of democratic system," he said, "where everybody’s voice is accepted -- not only accepted but necessary for it to reach its potential."

Act 2: Audience As Participants

And that's what Smith said she hopes to achieve with the unusual second act of "Notes from the Field." After more than an hour of her performance onstage for Act I, she turns the theater over to the audience for Act II.

The audience breaks into groups of about 20, then goes off to talk for about 25 minutes about what they've just seen. They're led by local volunteers.

Michael Sandel, a Harvard professor who teaches political philosophy, is one of the discussion leaders.

"It’s a chance to engage the audience in a broader civic discussion, to blur the lines between what goes on on the stage and what goes on in our civic life," Sandel said. "Our challenge will be to make the audience not just spectators but participants."

Kayhan Irani, who has been training the discussion facilitators, acknowledged that the experience could feel artificial.

"The one thing we have been really practicing in our sessions with the facilitators is practicing awkwardness," Irani said. "Like, just understanding that to be vulnerable and to be in a group of strangers is slightly awkward."

But she argued that "what we should feel is a little uncomfortable, a little more hungry" for information and a little more willing to get involved.

"So for some people the next thing might be really to take some sort of action, host an event, go get involved," she said. "Someone else, it might just be to read more and understand what is going on."

In Berkeley, Smith asked audiences to commit to one specific thing they'd do. Shelby was there, and he was inspired to say he would take music into prisons.

"And I was like, 'Well now I gotta go, I made a commitment,'" he said with a laugh.

And he's kept that commitment.

"So for the past three years," Shelby said, "I've been going to San Quentin, Folsom Prison; every month I go to juvenile hall."

Smith knows that's not for everyone. But she said she thinks everyone can do something.

She's particularly excited to see what happens in Boston, where she believes the many academic institutions and a rich culture of education research will bring out many people who can carry the conversation forward.

"And these people I think have a great potential when we have left," she said, "to network and to really do the work when we’re gone — when the circus has left the town."

She said she hopes that what she calls an experiment, the audience involvement and call to action, could lead to larger change.

"There’s just so much I can really do," Smith said. "But I do think one thing we can do in the arts is to apply ourselves to think about how can we increase and celebrate the idea of empathy and compassion. Because it ain’t gonna happen in business, it’s very hard to implement it in schools now, and so somebody’s got to do it."

Somebody like Anna Deavere Smith. Or Marcus Shelby. Or the teachers, students, cops and ordinary citizens that Smith hopes will take action in response to her call.

Clarification: Michael Sandel is leading a special discussion with the whole audience on Sept. 9, not the breakout discussions that are part of every performance. The Sept. 9 event will feature a panel of high school students, teachers, police officers and others.

This article was originally published on August 25, 2016.

This segment aired on August 25, 2016.