Advertisement

Mass. Schools Get More Money In The Latest Budget. A Lot More Is Likely On The Way

With the arrival of a budget compromise on Sunday, Massachusetts' public schools can likely look forward to an unusually generous bump in state aid next year.

Still, it's likely just a prelude to a bigger — and more contentious — overhaul of the way the state funds K-12 education, as lawmakers try to reconcile several different visions of reform.

It’s been almost four years since a state commission found that the state was dramatically under-funding schools, especially in low-income communities. Some estimate the shortfall to be as much as $2 billion per year.

That gap was due both to issues that affect every district — like the soaring cost of providing health benefits and special education — and to more local issues, especially keeping up with the demands of educating low-income students.

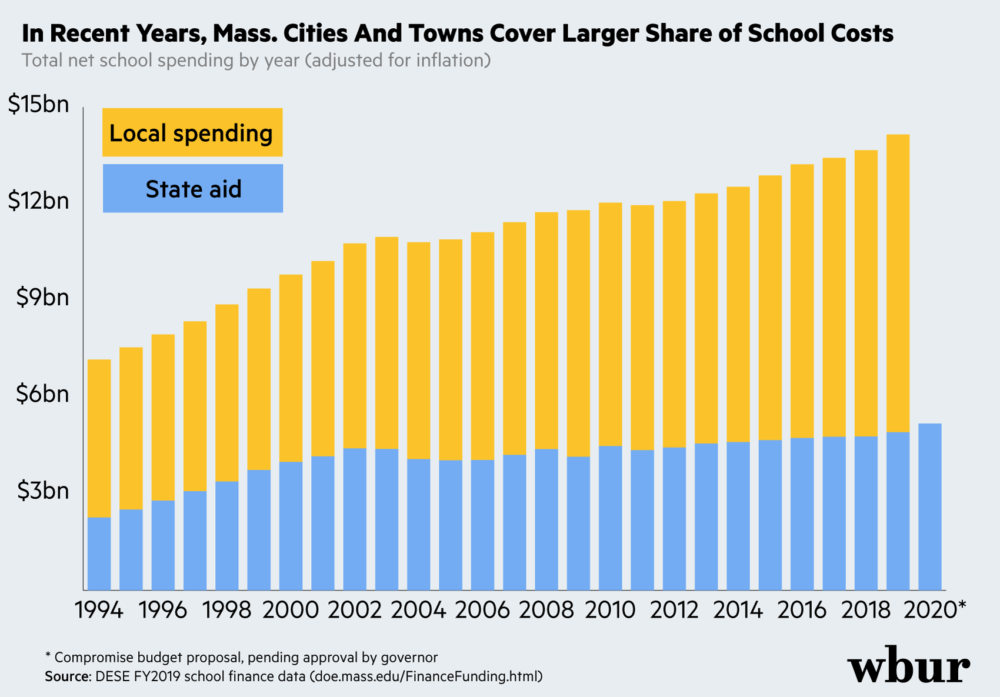

Many activists and educators greeted that report as a ringing alarm bell. And yet, in the four budgets finalized between now and then, the Legislature increased its Chapter 70 aid to schools only slowly: just 1.3% annual hikes, on average, after adjusting for inflation.

The budget released Sunday breaks the trend.

If signed by Gov. Charlie Baker, that budget would send $269.4 million in new state aid to schools, a 5.5% increase over last year. And it would make tweaks designed to better serve low-income students and districts like Boston that lose many students to charter schools.

Teachers and advocates are commending lawmakers for the sizable hike, though many are calling it a "step in the right direction" or a "down payment" as they await a deal that would promise escalating investment in schools over the course of the next seven years.

Beth Kontos, president of AFT Massachusetts, a teachers' union, said she's "encouraged" by the budget — not just by its hike in overall education aid, but also its targeted bumps to fund special education and "free, nutritious breakfasts" in low-income schools.

Kontos noted, in particular, that the proposed budget begins to set right a longer-lived inequity: by sending between $100 and $600 more to districts each year for each "economically disadvantaged" child they enroll.

But she emphasized that this is only a start, and that AFT's goal is "for every child to feel that we respect them." "We have curriculum that needs to be updated, books that are falling apart, desks that are defaced or disgusting," Kontos said. "I don't want it to be on our teachers to buy the books they need with a GoFundMe."

The idea that many teachers and schools in the state just aren't getting enough to do right by their students has of late become part of mainstream political discourse in Massachusetts — so much so that experts from opposite ends of the political spectrum seem to accept it.

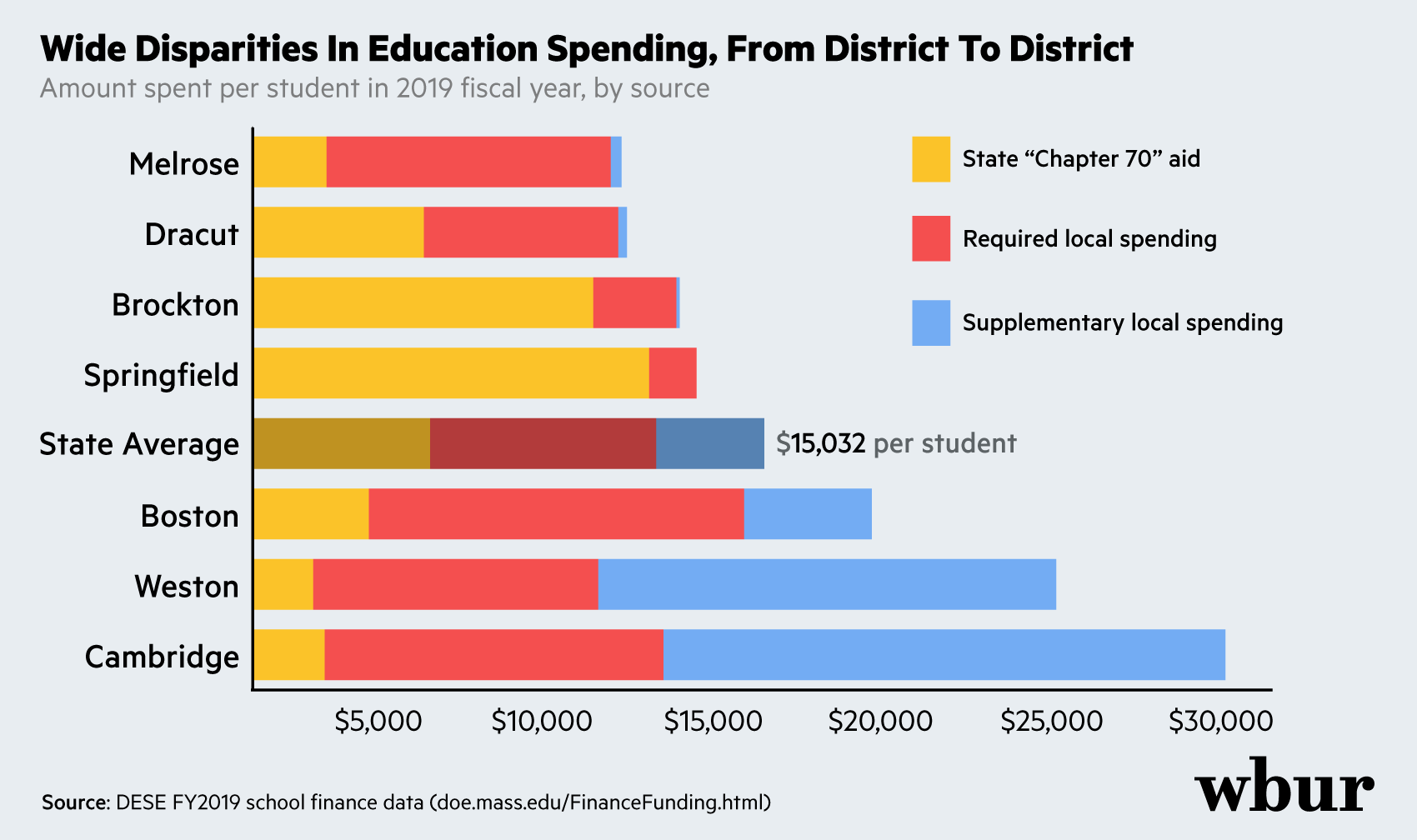

Greg Sullivan, research director at the right-leaning Pioneer Institute, was struck by the size of the budget's investment in schools. "But how will it be given out?" Sullivan asked. "There's still a need to help the most economically stressed communities" like Lawrence and Holyoke, which can spend as little as half as much per pupil as do their more tax-rich neighbors.

The disparity flies in the face of a growing body of research that finds that poor students need more funding to thrive in school — not less.

Colin Jones, a senior analyst at the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center (MassBudget), which tends to advocate for higher taxes and more state spending, agreed, calling the budget "a pretty significant agreement" on education but saying it needed to be fairly distributed.

Jones said that will depend on reform of the "foundation budget" formula. The state uses that formula to calculate the costs of schooling in districts based on their demographics — and as a result, how much aid each district gets.

The formula could be seen as state leaders' agreement on who deserves what in education. Without updating it, Jones said, "we’d be repeating that same argument year after year: How much do we do, and what are our goals?"

What Comes Next?

Almost every year, state aid to schools goes up (at least a little) to reflect rising costs. And last month Jones projected that the state would be set to spend $5.89 billion in aid to schools in 2026 if they kept to the status quo.

But two major bills are under consideration now. Both would bend the spending curve upward.

The first is the so-called PROMISE Act. It was introduced in January by lead sponsor Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz of Jamaica Plain and backed by Boston Mayor Marty Walsh. (The PROMISE ACT also has the support of all the state's teachers' unions; Kontos said she'd "love" to see it pass.)

According to Jones's projection, the PROMISE Act would add $1.4 billion in state aid to schools by 2026.

Later in January, Baker put forward his own, more modest bill, "An Act To Promote Equity And Excellence." It would add $459 million by 2026, according to the MassBudget projections.

The reason for the disparity between the two projections comes down, in large part, to their divergent handling of poor students. Baker's bill would gradually increase the low-income "increment" sent to districts for each of their poor students by 20%, while the PROMISE Act would aim roughly to double it.

Also, under Baker's bill, the new aid would come with some strings attached. For example, it would allow the state's education commission to more closely monitor struggling schools and districts, even withholding funds if they failed to show improvement.

That aspect of the Baker plan appeals to experts at the Pioneer Institute.

Jamie Gass, head of school reform at Pioneer, proposed going further: expanding the practice of state takeovers of under-performing districts, and allowing the state to appoint school committee members in proportion to how much money a district spends comes from the state. (Gass acknowledged this is a "controversial idea.")

His colleague, Tom Birmingham, agreed. Birmingham, who served as president of the state Senate when Massachusetts' landmark ed reform legislation passed in 1993, said "we squander an opportunity" if we don't attach reforms to the "massive infusion of new dollars" promised by this legislation. The Pioneer experts also warned that the state should be mindful of a coming "tsunami" of pension liabilities to be paid out to teachers.

Meanwhile, at MassBudget, Jones is skeptical of the need for "additional guardrails." In just the past few years, Jones said, "we've had increased authority for the commissioner, MCAS 2.0, [a new federal accountability plan], tools for looking at outcomes and measuring achievement gaps — lots of things, both at the state and federal levels. Meanwhile, we haven't updated funding in 25 years."

Kontos is more frank. "We have measures to keep accountability on the students and educators," she said. "What we would like to see is some accountability on districts: to make sure they have enough counselors, nurses — more boots on the ground!"

Behind closed doors, lawmakers are working to reconcile the two visions. They're working late into the summer, and similar bills have failed in the past. Still this time feels different. There seems to be an emergent consensus, that in the current climate of tax windfalls and wide inequity, $269 million really may be just a "down payment" on a lasting solution to the problem of school finance in Massachusetts.