Advertisement

'Blood, Bones And Butter' Tells Story Of A Chef's Life

ResumeGabrielle Hamilton, the chef and owner of the New York City restaurant "Prune" has gotten rave reviews for her cooking from Anthony Bourdain, Mario Batali, and Mimi Sheraton.

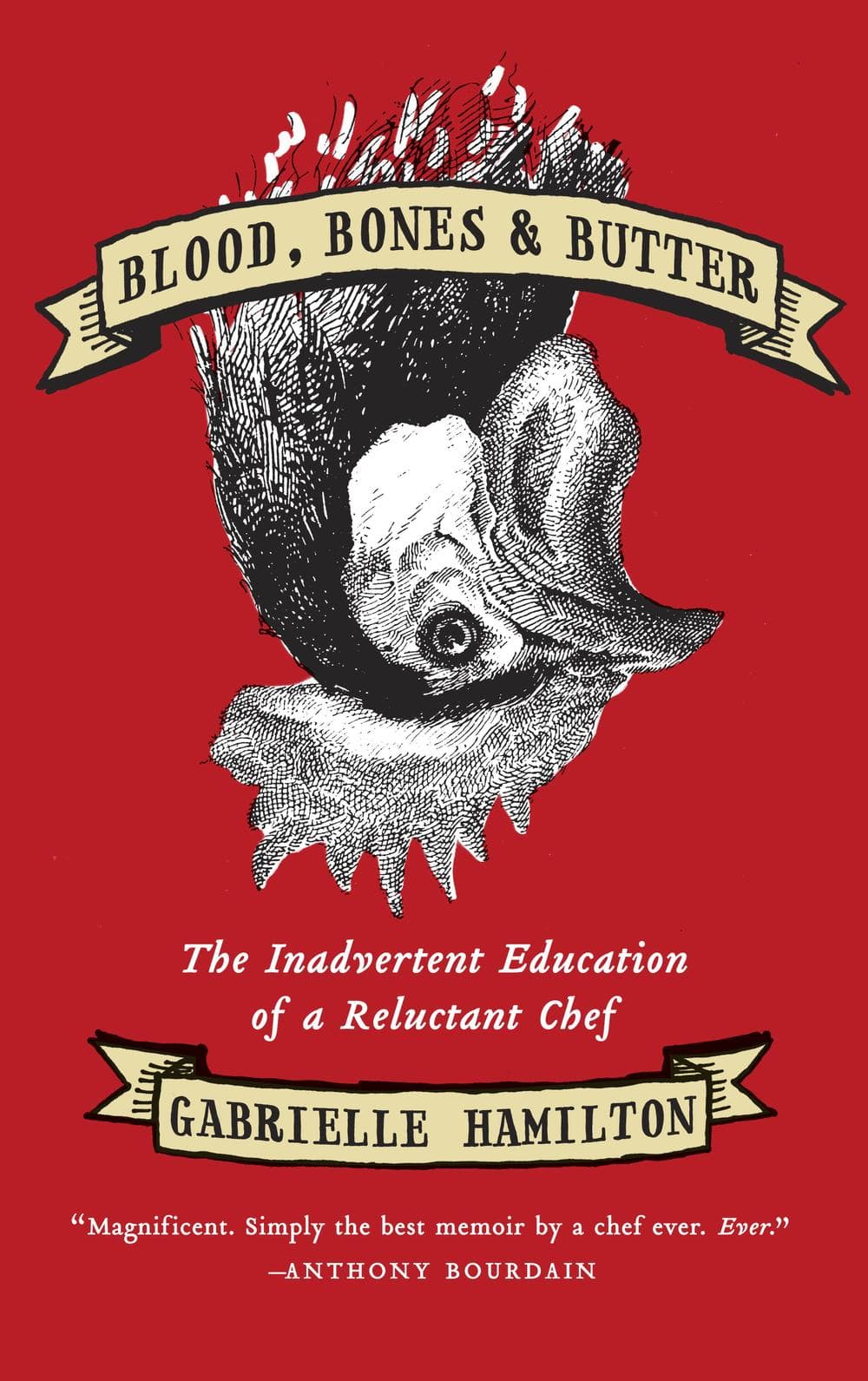

Now her new memoir "Blood, Bones & Butter: The Inadvertent Education of a Reluctant Chef," excerpted below, is also getting acclaim, Bourdain calls it "Simply the best memoir by a chef. Ever." Gabrielle writes about her idyllic childhood in rural Pennsylvania, how she fended for herself after her parents' divorce, and how she created the restaurant that's become a destination for food lovers.

Warning: Book excerpt contains language that some may find offensive

Book Excerpt: Blood, Bones & Butter: The Inadvertent Education of a Reluctant Chef

By: Gabrielle Hamilton

I was not looking to open a restaurant. That was never on my mind.

I was just dashing out to park the car one spring morning, when I ran into my neighbor Eric, a guy I knew onl y peripherally from years of living on the same block. I didn’t even know his last name, but we often saw each other during that hectic morning ritual of alternate side parking that New Yorkers, or at least East Villagers, seem to barely accomplish in time to beat the meter maid. It’s a twice a week early morning ritual, Mondays and Thursdays or Tuesdays and Fridays, depending on which side of the street you’re on, in which everyone on the block with a car comes rushing out of their building to move their machines, still wearing their pajamas and with pillow creases still marking their faces. Eric was sitting on the stoop in front of a longshuttered restaurant space mid- block, and as I zoomed by in my sweatpants and hastily slipped- on clogs, we waved. He said, “You still cooking?”

y peripherally from years of living on the same block. I didn’t even know his last name, but we often saw each other during that hectic morning ritual of alternate side parking that New Yorkers, or at least East Villagers, seem to barely accomplish in time to beat the meter maid. It’s a twice a week early morning ritual, Mondays and Thursdays or Tuesdays and Fridays, depending on which side of the street you’re on, in which everyone on the block with a car comes rushing out of their building to move their machines, still wearing their pajamas and with pillow creases still marking their faces. Eric was sitting on the stoop in front of a longshuttered restaurant space mid- block, and as I zoomed by in my sweatpants and hastily slipped- on clogs, we waved. He said, “You still cooking?”

I was, technically. I had taken an interim chef job at one of those huge West Side Highway catering companies where I had formerly been a freelancer while they performed a thorough talent search to find their real next chef. I was just a three-month placeholder, during the dead season, which is why I felt fine taking the job. I reasoned that it was a moderate way for me to make some money while I continued to write and to resolve my last lingering uncertainties about my place in a kitchen.

“I am, sort of,” I said.

“Wanna take a look at this space?”

I was off that day, with big plans to sit on my couch procrastinating the writing of my novel- in- progress.

“Sure. I’ll take a look. Why not.”

There was a faded yellow typewritten letter in the window from the former tenant—a French guy who had run a bistro that thrived for a brief but bright couple of years—advising customers that the restaurant would just be closing for a two- week vacation and renovation. They looked forward to seeing you soon! Bonnes Vacances! Two weeks had turned into two years, and I could see, from the second we stepped inside, that there had been no vacation planned at all.

“Bankruptcy,” Eric said.

It looked like the restaurant had desperately done business right up until 12:01 a.m., when the city marshal came and padlocked the place, leaving the coolers full of lamb shanks, dairy, and crème brûlées. There were racks of dirty dishes sitting outside the machine, which sat ajar, as if the dishwasher had just run downstairs for a few more clean towels and a gallon of pink liquid before running his next load. The pot sink was packed with dirty sauté pans. The pastry station had black shriveled pastry in the coolers, and the espresso machine had hard, spent pucks of powder fossilized into the ports. Next to the machine sat a stainless steel pitcher with long spoons in it, as if a café machiatto was in the works just as the city’s assessor walked in the door with his huge ring of keys. There were cigarette butts in the ashtray, as if the early waiter had already sat down and begun his paperwork and tip sorting at the end of his shift.

Eric, who owned a couple of units upstairs in the coop and who was now putting some effort into sorting out the mess of the abandoned storefront, showed me around the restaurant as I held my T- shirt pressed over my nose and mouth. The place was putrid. The floors grabbed the soles of my shoes with every step. So much rat shit had melted in the summer heat and commingled with the rat urine over the two years that the space had sat there idle that it was like walking on old glue traps. I had to run outside for gulps of fresh air after several minutes in the restaurant.

The electricity, oddly, had not been cut off but the light bulbs had died, and most egregiously, the freon had run out in coolers that still had running fans. When I opened a door on the sauté station reaching refrigerator, I was hit by a blast of fetid warm air coming from decomposed lamb shanks and chicken carcasses. There were legions of living cockroaches. The basement was very dark. Only one tube of a fluorescent flickered overhead. It was impossible not to jump out of your skin with the creeps with every brush of your own hair on your own neck. In the walk- in, by the dim light of a weak flashlight, I stupidly opened a full case of apples only to have a gray, sooty cloud of spores—like a swarm of gnats—fly up into my nostrils and eyelashes. Twenty- five pounds of apples had rotted away to black dust.

And yet, even with the cockroaches crawling over bread baskets and sticky bottles of Pernod, I could see that the place had immense charm. There was an antique zinc bar with just four seats that had been salvaged from a bistro in France and shipped over. There were gorgeous antique mirrors everywhere, making the tiny space seem bigger than it was, and an old wooden banquette, and wrought- iron table bases. The floor, under all that sticky rat excreta, was laid with the exact same tiny hexagonal tiles that had been on the floor of a crêperie in Brittany where I had worked for a brief period in my early twenties. Even when gulping the comparatively fresh New York City air once back on the sidewalk, thinking I might have been poisoned in some way, I knew the space was exactly “me.” There were ten sturdy burners. Just two ovens. And fewer than thirty seats. I could cook by hand, from stove to table, never let a propane brûlée torch near a piece of food, and if it came down to it, I could just reach over the pass and deliver the food myself. I knew exactly what and how to cook in that kind of space, I knew exactly what kind of fork we should have, I knew right away how the menu should read and how it would look handwritten, and I knew immediately, even, what to call it.

“Any interest?” Eric asked.

A thin blue line of electricity was running through my body.

“Maybe,” I bluffed.

This segment aired on March 9, 2011.