Advertisement

Will Super Tuesday Live Up To Its Name This Time Around?

Resume

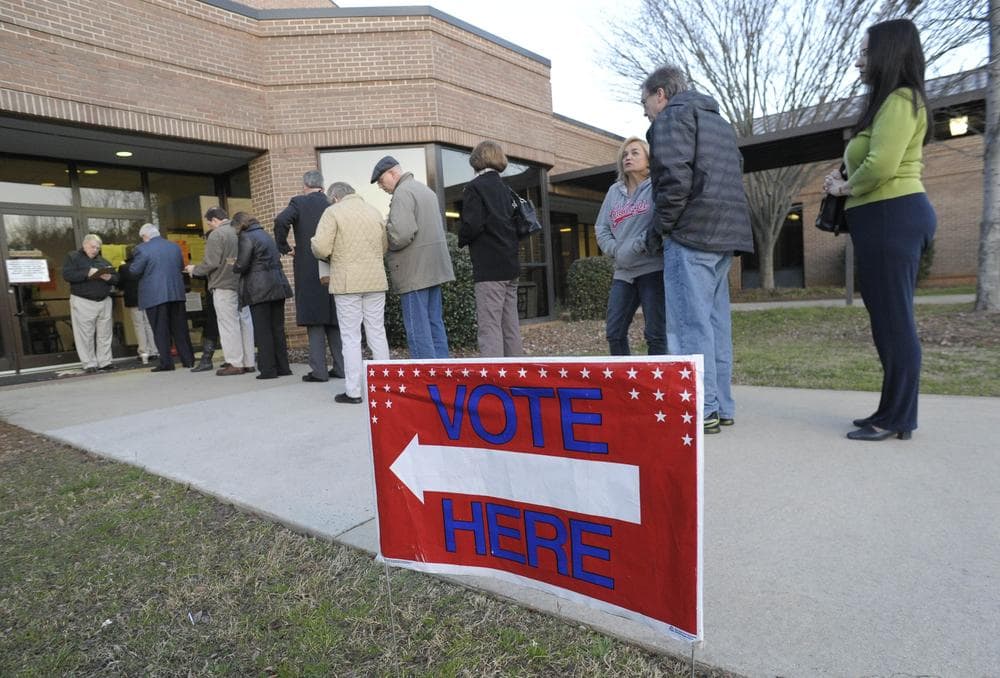

So it's Super Tuesday, a term that really entered our political vocabulary 24 years ago, when 20 states held primaries or caucuses on March 8, 1988.

Julian Zelizer, professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School, says that the states came together that day in reaction to the events of 1984, when Walter Mondale won the Democratic nomination.

Mondale was later slammed by Ronald Reagan in the general election, leading to frustration from Southern states, who wanted more say in the Democratic nominating process.

How Have Super Tuesdays Impacted The Race?

But in 1988, Zelizer says Super Tuesday didn't turn out how the Democrats may have wanted-- Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis, Al Gore and Jesse Jackson split Super Tuesday contests. And Dukakis, the northern liberal, got the Democratic nomination and lost to George H.W. Bush in the general election.

But for many candidates Super Tuesday has sealed the deal:

- In 1988, George H.W. Bush swept 16 out of 17 states on Super Tuesday and won the GOP nomination

- In 1992, Bill Clinton dominated Super Tuesday and won the Democratic nomination

- In 1996, Bob Dole wrapped up the GOP primary race on Super Tuesday

- In 2000, George W. Bush and Al Gore sealed their nomination bids on Super Tuesday

Guests:

- Julian Zelizer, professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School. His upcoming book is "Governing America: The Revival of Political History"

- John Faherty, reporter with The Ciincinnati Enquirer

- Chas Sisk, reporter with The Tennessean

Book Excerpt: 'Governing America: The Revival of Political History'

by Julian E. Zelizer

In the spring of 1995, I attended a session at the Organization of American Historians Conference at the Washington Hilton, which focused on the state of political history. When I walked toward the conference room I expected to find a small crowd, and one with little hope for the future.

In the spring of 1995, I attended a session at the Organization of American Historians Conference at the Washington Hilton, which focused on the state of political history. When I walked toward the conference room I expected to find a small crowd, and one with little hope for the future.At the time, the political history field seemed bleak. Senior practitioners, who, for at least two decades, felt that their work had been relegated to the academic dustbin, were demoralized and pessimistic. Graduate students such as myself entered the profession with a sense of trepidation, concerned about how our interests would be received in the academy.

When I entered the meeting room, I was surprised. The panelists spoke to an overflow crowd. The room was filled to capacity. Attendees were standing along the walls, and even outside the door in the hallway peering in. During the discussion, a generational debate opened up. While some of the older panelists and attendees expressed the predictable laments about the demise of the field since the 1960s, younger voices insisted that in fact we were on the cusp of a new era. They pointed to new scholarship that was starting to reenvision how historians wrote about politics by bringing back issues such as public policy and government institutions while integrating these subjects into broader narratives that dealt with social and cultural forces.

It was clear to everyone in the room that something was happening. The electric atmosphere suggested that change might be taking place after decades when U.S. political history had suffered professionally. As it turned out, the younger generation was right.

The problems for political history had begun toward the end of the 1960s, when a new generation of scholars entering the profession developed a stinging critique of political history as it had been practiced by legendary figures such as Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Richard Hofstadter.

Shaped by the conflicts of the 1960s over civil rights and Vietnam, the scholarly arm of the New Left had argued that political history, as it had been practiced since the founding of the profession in the 1880s, revolved around a narrow group of political elites who did not reflect the experiences of the nation. In the minds of rebellious graduate students, the presidential synthesis had produced a skewed narrative of the American political tradition that ignored intense conflicts over class, race, ethnicity, and gender that had shaped the nation since its founding. The differences separating most presidents were indeed minor, they said, but for them that was a reason to look elsewhere to really explore the national tensions beneath Washington’s surface. Claims about a liberal consensus that dampened serious divisions, they said, resulted from only looking at a narrow segment of the nation as opposed to accurately capturing the inherent character of the citizenry.

The social and cultural history revolution that followed in the next two decades pushed scholars to broaden their canvas to emphasize the study of American history from the “bottom up” and at the local level, focusing on questions like class formation and gender relations rather than political leaders, public policy, or government institutions. Whereas older historians had also understood the impact of social movements on politics, this literature relied on more quantitative precision to assure representative case studies and delved much deeper into local archives to unpack their stories.

French scholarship had an important influence on the rise of social history and the decentering of political history. The Annales school shifted the attention of historians toward the longue durée: big demographic, geographic, and socioeconomic changes that impacted ideational and institutional structures rather than the specific actions of political leaders at given points in time. The school, according to one scholar, treated political historians “with disparagement or even contempt . . . [political history] carries something of the aura of excommunication by the pope.”3 American social and cultural historians drew on these analytic methods as they turned their attention to similar kinds of issues within the United States, such as the formation of the middle class, the process of urbanization, or the evolution of race relations.

Social and cultural historians produced a wealth of knowledge about the formation of the nation from the bottom up. Instead of finding a country that shared some kind of ideological consensus and lacked the kind of social conflict that characterized Europe, these historians found a nation ridden with tensions over race, gender, and ethnicity. Some of the most vibrant scholarship took place in the field of labor history. Scholars examined the demise of a society where workers had maintained strong control of the shop floor in the nineteenth century to one where management and owners maintained much stronger control. Workers organized in response to the need for protecting certain kinds of wage guarantees and the desire to seek more autonomy in their communities. Cultural historians, who began to thrive in the late 1980s, were interested in studying the construction of ideas. Influenced by anthropology and literary studies, they also looked into the questions of whether cultural media such as films or television were hegemonic forces that shaped social identity or whether Americans brought their own interpretation and meaning to these experiences.

And then, slowly, almost imperceptibly, history writing began to change. During his presidential address to the Organization of American Historians in 1986, “The Pertinence of Political History,” published in the Journal of American History, historian William Leuchtenburg made an unexpected prediction amidst these historiographical trends. Leuchtenburg, whose own work focused on the politics of the New Deal, anticipated that the situation was about to change. Understanding this was an unconventional perspective, to say the least, he wrote, “When someone tells you, as I am about to tell you, that the historian’s next frontier is political history, there would appear to be only one sensible response: You have got to be kidding.”

To defend his position, Leuchtenburg highlighted slightly more optimistic developments than other political historians of his time. First, there was a group of political scientists, such as Theda Skocpol and Stephen Skowronek, who were writing about the state. Practitioners of “American Political Development” (APD) designed an approach to studying politics that was fundamentally historical. Focusing on the development of institutions, they were interested in the structural constraints faced by policymakers. Some of the analytic strategies for the new political history emanated from the social sciences. These scholars were writing about how the foundational structure of American institutions shaped the evolution of national politics. They were particularly interested in the limits of change given the power of institutional structures to constrain policies. Second, there were some social and cultural historians who started to find their way back to politics, broadly defined, in response to a feeling that the field of American history had become too specialized and fragmented. There was no sense of what held all the pieces of American history together.

It turned out that Leuchtenburg’s prediction was correct. When he delivered his presidential address, announcing the return of political history, Leuchtenburg had a lot of evidence to show that political history was, once again, in vogue. Since the early 1990s, the field of American Political History has returned to the forefront of the profession, but not the same political history of the past. The field, once marginalized, has been remade, and in vibrant fashion. There were many reasons that a new generation of scholars turned to political history. Many had concluded that politics had been downplayed so much that huge areas of American history had been left out of the literature. Like all scholarly cycles, they saw a huge hole that existed in the literature and moved to fill it. Social and cultural historians, they said, ironically had made it more difficult to evaluate the structures of power within which different social groups and grassroots movements existed. Furthermore, graduate students who entered into the profession in the 1990s had come of age during Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s, when they saw the impact that a shift in control of political power could have on the nation. As more historians developed an interest in writing about the twentieth century, particularly the decades since the New Deal, it was simply impossible to ignore the role of the state.

The new political historians have offered fresh and original approaches and interpretations about U.S. political history. They have punctured the myth that there was any kind of consensus that shaped political debate in any period, while simultaneously revealing how average citizens had a profound impact on national politics as a result of mass movements. Others have returned to their focus on political elites, from presidents to legislators to intellectuals, but they have done so by situating them within particular institutional contexts. They have shown how the structure of institutions shaped what political elites could or could not do at the same time that they have broadened the range of political elites who they include in their studies. The new political historians have challenged conventional assumptions about political development, such as the nineteenth century being a period when the federal government was absent from public life. They have taken a period thought to be stable and consensual, such as the decades between the New Deal and the 1970s, and shown them to be riddled with tensions and contradictions. Even those scholars who have returned to the subject of the presidency— the centerpiece of political history before the 1960s— have tackled the subject through analyses that avoid presenting the chief executive as a free- floating leader who embodied the spirit of the era. Influenced by the findings of the previous generation of political historians, the new political history has provided rich narratives full of conflict, tension, and contingency, shedding many of the assumptions of previous eras.

In developing my own research, I had to make significant choices about how to organize my narratives and where to focus my questions. Over the past fifteen years, I decided to emphasize three themes in an effort to develop fresh narratives about the political past: policy, political institutions, and electoral politics.

Focusing on policy has been attractive because it has helped me to break free from traditional time frames used in political history, ranging from presidential centered accounts, to the cycles of liberalism and conservatism, to the modernization schema that claimed the turn of the century to be the watershed moment in American political evolution.

While those older frameworks have much to offer, I was eager to experiment with other ways of organizing political time and testing to see whether the existing scholarship had missed watershed turning points or historical patterns. Policy history does not fit into most existing chronological structures. Indeed, different policies have different timelines, something that makes the subject enormously challenging. As historians delve into different policy sectors, they have begun to perceive more complex chronological structures of political history than previous historians have suggested.

Policy history has also allowed me to incorporate a more diverse group of actors into narratives than previous generations of historians have been able to do. The tensions between scholars who study elite politics and grassroots politics quickly dissipates when policy is made the center of inquiry. After all, policies are crafted by government officials in alliance with, and in response to, other social and political actors. Federal, state, and local policies influence—and are reshaped by— all types of social actors and institutions.

I have tried to understand how policy communities have played such an important role in Washington. Policy communities consist of party officials, leaders and experts from umbrella interest group associations, staff members of the executive and congressional branch, bureaucrats and administrators, university professors, independent specialists, editors and writers of the specialized policy media and think tanks. These communities work across institutional lines and create some kind of consistency in the fragmented political system over time. They attempt to sell their ideas to powerful elected officials in the White House and in Congress.

Recent work in policy history has started to accomplish what many scholars had been talking about in abstract theory for years: breaking down the once-rigid barriers between state and society through the use of policy as the object of study and not locating scholarship in any single social realm. Policy likewise has encouraged historians to examine institutions that are often overlooked by historians, such as the mass news media, local government, and the non- profit sector.

The second organizational theme of my research has been political institutions, with a particular focus on Congress. My interest in institutions grew out of the excellent work by historical political scientists in the field of American Political Development who were looking at how institutions constrained and shaped American politics. I found the study of institutions to be an exciting way to think about the political past and to situate political leaders in some type of organizational context.

My goal has been to show how the clash of our democracy has centered on a competition between multiple institutions, organizations, and political actors who have been constantly contesting the formation of policy and vying for power. The problem with some earlier work was that it was so focused on presidents or the “people” (vaguely defined) that their work missed other critical actors whose inclusion provides very different perspectives about how political history operated.

Most important to my writing on institutions has been bringing Congress back into political history. Congress offers an opportunity to break down the division between state and society, to reorganize our chronology of politics, and to see the close intersection between politics and policy. Unfortunately, one of the biggest oversights in the literature on political history had been Congress. Overshadowed by presidents and social movements, legislators had remained ghosts in America’s historical imagination other than as a regressive foil to liberalism. When Congress appeared in a few academic books, it was treated as an archaic institution that functions as either a roadblock or a rubber stamp to proposals that emanate from the executive branch or from mass social movements. Congressmen received shallow treatment, if they were even mentioned. Presenting congressional members as caricatures who merely supported or opposed presidential initiatives, these histories described uninteresting, provincial politicians who were concerned exclusively with securing support from the strongest interest in their constituency. They provided little systematic treatment of how Congress as an institution operated within the corporate reconstruction of American politics. When writing about federal government, practitioners of American Political Development and the organizational synthesis tended to concentrate on the expansion of the administrative state with its bureaucracies and expertise. Congress seemed to them a premodern relic, interesting only for its gradual loss of power and an occasional decision to expand its administrative base. The persistent influence of Congress contradicted the teleology of their story of modernization.

Congress is a large, diffuse institution, which makes it difficult to craft a narrative to describe it. I have incorporated the history of Congress into larger narratives of politics through two main strategies. The first has been to focus on particular powerful legislators such as Wilbur Mills to tell the story of the institution. Another has been to focus on how Congress works, using the legislative process, and how it has changed, as a way to understand the evolution and structure of the institution.

My work has documented how Congress has been an active force in national politics as opposed to the traditional depiction of a passive institution whose members usually react to the pressure bearing down on them. Although Congress is extraordinarily sensitive to democratic pressure, the members of Congress have also been able to initiate their own policy proposals, develop their own agenda and interest, and form their own distinct institutional identity. Finally, in recent years I have been organizing more of my research around the rather traditional themes of campaigns, elections, and partisan strategy. In doing so, I have attempted to bridge the interests of newer and older generations. While using policy and political institutions as a framework for analyzing politics, I have attempted to situate our studies within the basic contours of our democratic system: electoral competition.

The dismissal of “old- fashioned” political history, which has had fruitful results by pushing historians to think of a broader constellation of causal forces in politics and broadening the number of actors who were included in narratives, simultaneously relegated certain key elements of our democratic system— including elections and partisan competition— to the sidelines. To fully understand how policies and institutions have evolved, I have found it essential to analyze their relationship to the electoral competition that Americans undertake every two years.

Electoral politics also allows a window into different policy areas and how they intersected. Instead of looking at one issue, a focus on elections forces historians to see the political landscape as historical actors did and in the same time, one punctuated by regular elections. Many of the most interesting sources of friction in the nation’s political history have derived from the clash between different policies as politicians tried to sell their agendas to voters and to maintain political support for their programs. The relationship between different policies often influenced the formation of each other, and the tensions between different policies have impacted the strengths and weaknesses of politicians in the electoral sphere. Historians, as the people they study, must be attuned to that political reality, even as they study policy formation, state- building, and social movements that stretch well beyond election cycles.

The following essays constitute my efforts to participate in the rebuilding of the important field of U.S. political history. The book is divided into four thematic sections. The first covers one of the ongoing concerns in my career, the historiography of political history. In addition to writing about specific moments and leaders in American politics, I have been continually fascinated with the intellectual underpinnings of the field and the multiple analytic foundations upon which it is built. The feelings about political history— both those that have objected to it and those that have supported it— are so intense that they often lack a sophisticated understanding of the actual origins and development of the field. By offering such an analysis, I have hoped to make the new work on political history even stronger.

The second section turns to the theme that shaped the first stage of my writing, the challenges imposed by fiscal constraint in American politics. Much of the early literature on the American state claimed that the United States was a “laggard” compared to comparable Western European democracies. To explain why the United States developed social welfare programs so much later than other countries, and often much more meager in size, scholars emphasized the weakness of the social democratic tradition in this country as well as the tensions over race and gender. In contrast, my work looked at fiscal challenges that I believed were equally as central and caused problems even when social democratic sentiment was strong. At the same time, seeking to move beyond the literature about American Exceptionalism, I used the issue of taxes and budgets to look at how policymakers were able to use innovative fiscal strategies to build programs within the constraints that they faced, such as Social Security and Medicare.

The next phase of my writing, the focus of the third section, revolved around the impact of the political process. In my work on the evolution of Congress I saw how the political process, and the changes that occurred within that process, often defined political eras. By ignoring the process, historians had tended to overlook essential elements in politics. Legislators and other policymakers depended on their mastery of the process to advance their goals and sometimes fought for substantive changes in the political process when reform came to be seen as crucial to overcoming a political coalition. My studies on process pushed me further toward understanding the centrality, as political scientists were writing about, of institutional design in politics. It also brought me further into the relationship between state and society.

Finally, the last section looks at the scholarship that moved me toward the intersection between policy and politics. While much of my earlier work was concerned with examining the autonomous spaces and defining cultures that shaped policymakers in Washington, by the most recent phase of my writing, expanding on some of the issues I looked at in my work on congressional reform, I was particularly concerned with reconnecting the state to its electoral underpinnings. I specifically chose the issue of national security— a policy domain that has been furthest removed from domestic politics— to highlight how these connections worked. Doing so enabled me to bring some standard topics in political history that had been downplayed in recent scholarship, such as elections and partisan strategy, back into our narrative about the state. My hope is that through this work I have and will continue to advance the new political history and to promote a style of analysis that scholars, students, and general readers can continue to grapple with and advance in the coming decades.

Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press.

- Washington Post: Super Tuesday Tracker

This segment aired on March 6, 2012.