Advertisement

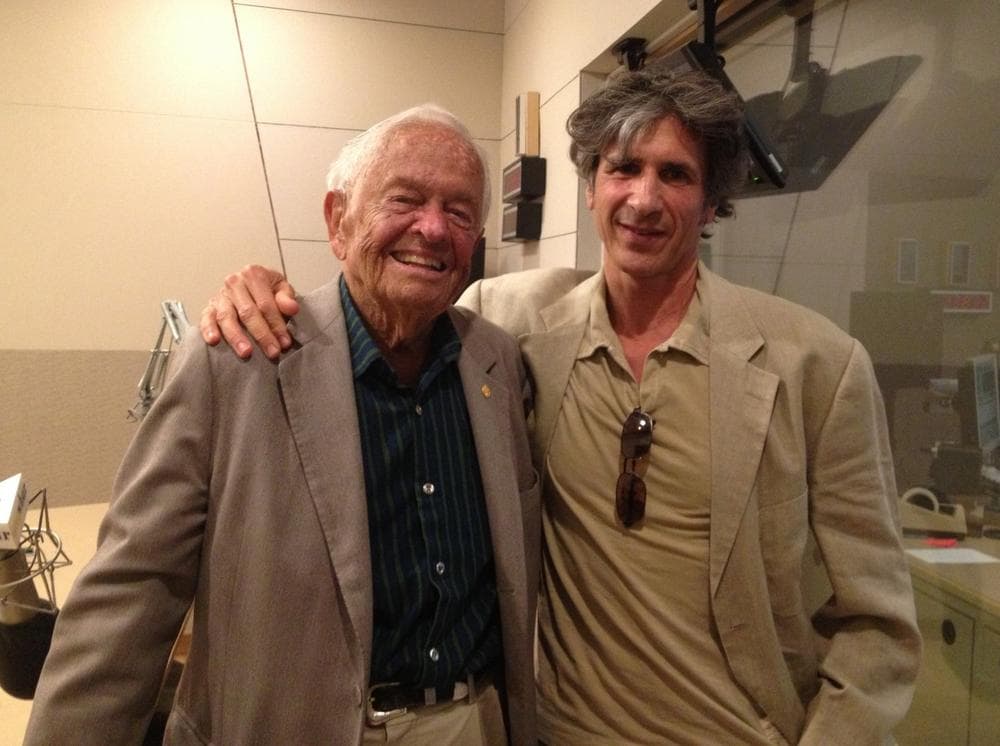

'Baby Whisperer' Reflects On Six-Decade Career

Resume

If you've ever had a baby, you've probably taken the advice of Dr. T. Berry Brazelton — perhaps without even knowing it.

Called the "baby whisperer," Brazelton changed the way we think of infants through his six decades of practice and his long-running cable program, "What Every Baby Knows."

Building off the work of his hero, Dr. Benjamin Spock, Brazelton theorized that babies are unique and use body language to communicate.

Brazelton encouraged parents to trust their own judgement about their children.

Now at 95, Brazelton is out with his own memoir, "Learning to Listen: A Life Caring for Children," (excerpt below) in which he looks at how his own upbringing influenced his life.

____Interview Highlights____

On bringing parents into his research

"When I started — and it's happened again now — people were just sort of run through like they were on a conveyor belt. But I went into pediatrics because I loved kids. I wanted to get inside their brains. I very quickly realized that I couldn't do it unless I understood what their parents saw in them, so I began to try to like parents. And since I'd had a mother that liked my brother but not me ... I had a hard time liking parents. But when I finally did, I found that that they could tell me so much. And I found out that even in the first two or three months, a child used his behavior as his language."

On answering the question "How am I doing as a parent?"

"I use a baby to capture parents right from the first. I can do this with even drug-addicted parents or abusing parents by demonstrating how the baby will chose the mother's voice rather than mine, and the father's voice. And every father I've ever done it with just grabs that baby and says 'Oh my God, he knows me already and he's a person.' And they begin to see this baby completely differently."

On how he's kept going all these years

"I was in Croatia after that nightmare over there, and this psychologist who was working with all of these children who had watched their parents raped and murdered and hung, came and said, 'I'm so depressed Dr. B, how do you keep yourself from burning out?'

"And I thought about it and I thought, well why, I never thought about burning out. Then I said, yes I do. I go and play with a newborn baby and I see how exciting a baby can be and what that baby can tell us about himself and he'll lead us right out of our burnout."

____Book Excerpt: 'Learning to Listen'

By: T. Berry Brazelton, MD____

Infancy and Early Attachment in Japan

In 1983, I was invited by the Japanese government and my friend Noburu Kobayashi to come to Japan. Noburu (or Kobey, as we called him) and I had met at various international conferences. A pediatrician, he held a high position in the government, involved in infant health. When he learned about my scale, he sent one of his students to be trained. Noburu wanted him to train Japanese doctors to use the NBAS all over Japan. Noburu had a great friend and advocate, Mr. Masaru Ibuka, the former CEO of Sony. He was powerful and very interested in fostering Japanese awareness of the importance of infancy and of early attachment of parents to their infants. He saw that Japan was about to change, with more and more women in the workforce, and he wanted to be sure to protect the mother-child relationship.

An unusual event in Japan had taken place: it was reported that over a period of two years, several eight- and nine-year-old boys had killed their mothers. These tragedies were blamed on the intense desire for upward mobility among Japanese parents. They pushed, pushed, pushed their children to get into the right child-care center, the right preschool, the correct grade school, and the right secondary school. When the child didn’t make it, some became so upset that they killed the only person they could blame: their mothers. This was absolutely frightening to the Japanese government, as well it should have been. Mr. Ibuka and Dr. Kobayashi made plans to get an unusual team of experts together to travel all over Japan, talking about early attachment and its importance. Jane Goodall, who worked at the Gombe Reserve in Africa for chimpanzees and may well know more about chimpanzee nurturing than anyone in the world, was invited. A famous Australian child psychiatrist, Paul Campbell; a French educator; and Chrissy and I were to go.

When we arrived in Japan, we were housed in a fabulous old inn. The rooms were traditional Japanese: mats on the floor on which we slept; paper walls, which we rolled back to go from one room to another; bathrooms with squatting toilets. So many things to learn in a new culture! The paper walls were magnificent, with very subtle designs, but one could hear everything from one room to another. We got to know each other better than we had expected.

The four of us “experts” went from city to city in Japan: Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, Nagasaki. Jane talked about her chimp babies in just the way I talked about our human babies. She showed how she held them gently out in front of her, to talk to them face to face. She had superb films of chimp mothers and even fathers nurturing their babies in the wild. What a delight it was to compare notes with her. As we went around to each city, hundreds of parents gathered for each presentation. None of us could speak Japanese, but that didn’t seem to dampen the enthusiasm. We were told that we were making an impact on Japanese parents. Hard to believe.

In Osaka, a prominent private researcher took Chrissy and me out to his reserve so we could observe nonhuman parent-infant interaction “in the wild.” In Nagasaki, an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Tomitaro Akiyama, introduced himself. He had translated the NBAS into Japanese and taught people to use it. In Japan, he explained, orthopedists are responsible for early intervention with children with special needs. He was interested in starting early intervention with these children from birth onward. At his hospital, they did very well in making up for motor delays, but he said that the children didn’t “make the progress he’d like in cognitive and emotional development because their parents won’t stay involved.” “Especially on the GotoIslands off the coast,” he said, “we can’t get parents interested enough to bring their children to us for early intervention.” He asked for our help.

Of course, I was intrigued and challenged. I assured him that I was ready to help, but, in order to be of any real use, I’d have to understand the culture much better than I did. “Would you be interested in coming to help us study these babies?” Of course I would, but I told him that we’d have to plan ahead for it, because I had a heavy teaching load at Harvard. He assured me that it would be possible and asked me to come the following year to study the babies and the culture on the GotoIslands. I could live there for a month at a time.

The GotoIslands are part of a chain in the Pacific from Okinawa to Korea. There are 140 islands in all, 5 main ones. (Goto means “five” in Japanese.) They were the last stops for sailing ships before leaving for China. They were undeveloped, still traditional fishing islands. Their whole economy is fishing. The men fish; the women mend nets and clean fish.

My son, Tom, and I went. We lived on the main island, Fukue, for a month. We enlisted thirty newborns for our study. At birth, the newborns were sturdy, beautiful, quiet babies who paid attention for prolonged periods. Their movements were liquid and gentle, and their fingers and toes were freely involved in their ballet-like movements. Like the Mayan babies, they were born and raised in the context of low-keyed motor activity, and so a newborn would pay attention to a soft rattle, a red ball, or your face for as long as thirty minutes without a break. I had been able to produce at most three to five minutes of tracking and listening in US newborns. This difference in the ability to pay prolonged attention was amazing to me, representing differences in genetic endowment and early environment. I decided to see how basic this prolonged attention would be if the environment were different. In the GotoIslands, women were quiet, slow moving, and never exposed to loud noises or activity. So I also observed mothers and infants in Tokyo. There, women were dashing around amid loud noises, traffic, and the like. Their newborns still had long attention spans, but not thirty minutes. They managed about eighteen minutes without a break. Later, a study of Asian babies in San Francisco showed that a newborn’s attention span there was down to twelve minutes. We felt this was a great example of the effects of experience before birth in shaping the behavior of the newborn.

Mothers in the Gotos walk slowly and live a quiet life. They talk to each other in low-pitched voices. Tension is not high in the GotoIslands, as far as we could observe. The fetus’s experience during pregnancy is a gentle, calm, well-fed one. In Tokyo, mothers are under much more stress. They walk differently; they rush to cross an intersection, looking up and down then hurrying across the street. All day, their movements and lives are more punctuated with jerky, tense movements, and stressful, noisy events. These provide the fetus with a different experience than that in the Gotos. In San Francisco, the effects of a stressfully active life are even greater. Nature and nurture already work together to create differences at birth. Add these to the effects of very different lives ahead. It isn’t hard to visualize the different kind of adults this will produce.

The Goto mothers (who had been mending nets and cleaning fish until they delivered) stayed in the hospital for seven days. Then they were sent to their mothers’ homes. There, they were expected to regress completely. Wrapped in a futon, each with her baby next to her, they were treated as babies themselves for one month. Their only job was to feed their babies. When they needed to go to the toilet, someone helped them. They were fed by chopsticks “like a baby.” Spoken to in baby talk, they responded in baby talk. Chisato Kawasaki, a pediatrician who was with us, documented the fact that there were no postpartum depressions after this early treatment. In Japan, a new mother could regress to her own babyhood for one month.

The thirty newborns we evaluated on the GotoIslands were half from fishing families, half white collar. We scored them by their performance on the NBAS, especially for their responsiveness to faces and voices and to nonhuman stimuli, for their motor fluidity and competence, and for their ability to soothe themselves when they were upset. We planned to see whether these scores predicted how well the babies would do on cognitive tasks later on. We returned every two years to evaluate them. At first we used the Bayley exam, later the Stanford-Binet. Each year, these exciting babies maintained high scores. The children all progressed equally through the third year. Then, half of them continued to make optimal progress on the test scores, but the other half began to level off and even to lose levels of IQ functioning by the age of five. Those babies who lost IQ, however, were well equipped to respond, and, with pressure, extra time, and assurance, they could achieve the higher levels of their peers. It became apparent that it was not the ability to achieve optimal scores but the motivation and the excitement of being tested that were significantly different. The white-collar parents who wanted their children to succeed in the corporate world of Japan were pushing them—four-year-olds in preschool, then school. The fishing parents were not pushing their children to perform cognitively. They expected them to stay on the island and fish. The potential of the child in the cognitive area was not their measure of success.

When we returned several years later, the fisherman’s children were in school, but relaxed, content with joining their parents in their traditional work. Children pressed by their parents were likely to be tense, often with problem behavior. Many of them had gone to the mainland to be prepared for high-powered careers and thus were already out of touch with their families.

Dr. Akiyama was very grateful for the ideas we could give him about how to work with new parents. We agreed that the time to capture them for early intervention if their baby was likely to have special needs was soon after birth. Then, sharing with parents the work necessary for early intervention would be a way to approach these isolated people. It meant that we had to train a pediatrician or neurologist (or orthopedist) from Fukuoka to evaluate all newborns for any neurological impairment or any question about development that showed up on my newborn assessment. Akiyama was eager to institute this, and the Nagasaki University School of Medicine became a very active site for training physicians from the islands as well as from all over Japan. They are still an active NBAS site and have published many papers on its use for diagnosis and prediction.

Dr. Akiyama arranged for Kevin Nugent to join me on our visits every two years. We helped his Nagasaki staff train eight to ten physicians each time. Meanwhile, we’d go to the Gotos each visit and follow up on our original babies. We grew devoted to all the Nagasaki team: ShoheiOgi, Chisato Kawasaki, and Tomitaro Akiyama.

Excerpted from the book LEARNING TO LISTEN by T. Berry Brazelton, MD. Copyright © 2013 by T. Berry Brazelton, MD. Reprinted with permission of Da Capo Press.

Guest:

- T. Berry Brazelton, pediatrician and author of "Learning to Listen: A Life Caring for Children."

- Joshua Sparrow, psychiatrist and director of the Brazelton Touchpoints Foundation.

This segment aired on June 5, 2013.