Advertisement

Methodist Pastor Faces Last Church Trial

Resume

Reverend Frank Schaefer was brought to trial by the United Methodist Church for officiating his son’s same-sex wedding, and defrocked at that trial after he said he could not uphold Church doctrine banning same-sex weddings.

Schaefer told Here & Now's Jeremy Young how he felt after he made that statement at his trial.

"For the first time in a long time I felt no fear," Schaefer said. "I didn't care if people were going to defrock me or stone me to death. You know, I felt at peace. I knew I had done the right thing."

Schaefer was later reinstated, but now faces a final church court which will decide whether he can continue to serve as a clergy member.

Schaefer says he had to act the way he did toward his son, Tim, because it was part of his beliefs.

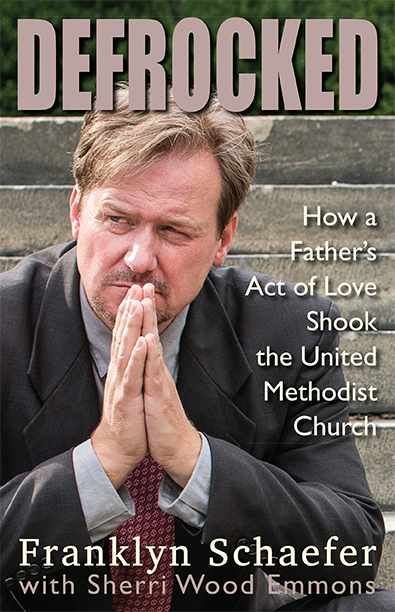

Book Excerpt: "Defrocked"

By Frank Schaefer

PROLOGUE

ON NOVEMBER 19, 2013, I sat in the witness stand of a makeshift courtroom at a church camp in Eastern Pennsylvania, the same camp my children had attended years earlier. The day before, a jury of my fellow pastors had found me guilty of performing a same-sex marriage and of violating the order and discipline of The United Methodist Church.

Before the court meted out my punishment, I now had the opportunity to plead my case. I faced the very real possibility of being defrocked and losing my livelihood. My counsel had crafted a carefully worded statement for me to read before the judge and jury. But as I looked out at my family and supporters in that room, at the sea of rainbow-colored stoles gathered there, I knew I could not read it.

Instead, I spoke from my heart. I told the court I could not uphold the teachings in The United Methodist Church’s Book of Discipline that said homosexuality was incompatible with Christian teaching. I was now and would continue to be an advocate for my gay brothers and sisters in the church and beyond. I said that I would continue to minister to all people equally, regardless of their gender, nationality, race, social status, economic status, or sexual orientation. And I called on the church to stop treating gay people as second-class Christians.

I did not ask to be put in an advocacy position, but there I was. My road to that place was a long one, beginning with evangelical, conservative roots. It was not a planned journey, but it became my journey—a journey redirected by an act of love for my gay son, the story of a father’s love for his son.

This is my story.

DEEP ROOTS

I WAS BORN AND RAISED in Wuppertal, a mid-sized city in western Germany with a rich history, not too far from Cologne. In the years leading up to the Second World War, there was a movement within the church in Germany that was opposed to what Hitler and the Nazis were doing in the country. It’s called the Confessing Church. Great theologians such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Karl Barth founded the Confessing Church in Germany; the Barmen Declaration, which was mostly formulated by Karl Barth, was adopted at a council meeting right there in my hometown of Barmen in the Gemarker Kirche. So we had a keen awareness of the Confessing Movement in Wuppertal. In fact, Wuppertal is the city with the most Christian denominations represented in all of Germany. And that’s where I was born and raised.

Born in 1961, I grew up as a child of the Baby Boomer generation. Our classes at school were so full then. I remember in first grade, there were thirty-six children in a classroom with one teacher and no assistant. Kids were kind of invisible then. It was a time when, wherever you went as a child, you were to be seen and not heard. Even in church. Maybe especially in church.

I was not raised a Methodist. The Methodist Church is fairly small in Germany. I was baptized in the Reformed Church, where my grandparents belonged. But when I was six or seven years old, my parents joined a Baptist church after they experienced a spiritual awakening, and they became very committed evangelical believers. They started to attend a Baptist church, and that’s the church where I grew up and got most of my Christian education.

My mother’s father, Opa August, was a part of the Confessing Church. He was furious with what was going on in Germany in the prewar years. He was totally opposed to Hitler. He wouldn’t allow my mom or her sister to join the Hitler Youth, which was similar to the Girl Scouts in the United States today, but it was part of the Nazi program to “educate” the young generation.

My grandfather refused to fly the flag with the swastika on it. Because of that, I was told that my grandparents’ house was the only one on the block that never had any mounting for a flag. He was arrested when the Nazis found out he was opposed to the government and they threw him in jail. And it was only because he had such great standing in the community that he was released. He was an elder in the church and very well-respected.

My dad’s father, Herman Schaefer, was part of the Nazi Party. I don’t know how much he was involved, whether he was active or if he only belonged because he was a businessman and joined so as not to lose out on business deals. He was drafted and fought in World War II and he never came back. As far as I know, he is still officially missing in action. He was actually a Red Cross truck driver. So I want to say that, maybe, because of that, he was a Nazi in name only. Maybe that was his way of saying, “Well, if I have to be part of this war, I can do something humanitarian.” I don’t know this for sure, but I want to give him the benefit of the doubt.

My Opa Herman was the one who never came back from the war, so I never got to know him. My dad was only three or four years old when he saw his dad for the last time.

Even in the 1960s, Germany was a sort of post-war culture. The economic recovery happened in the 1950s, so many people were doing a lot better financially, but it was still a struggle for most families, including mine. The Nazi regime and the war had definitely left their mark. I heard gruesome war stories growing up. Every time a siren went off somewhere, it seemed the stories came out. Sirens were how they had known the bombers were coming and they had to hurry to either the community bomb shelters or their basements. There were stories about streets burning as phosphor bombs hit, charred corpses my grandparents had to step over, people lost in the rubble of their homes, children screaming.

My grandmother on my father’s side, Margarete Schaefer, had to flee from the family estate in East Prussia as the war drew to a close, as Russian soldiers were rushing in. Out of fear of retaliatory acts, she fled to western Germany with four young children, along with thousands of her compatriots. She had to walk for miles pulling a cart with a few belongings and with her two younger children.

We grew up knowing their fear and how traumatic it had been for them. In Wuppertal, I believe something like 40 percent of the buildings were destroyed in RAF bombings, and the memories of the destruction were ingrained in peoples’ memories. Moreover, when I was a teenager, I learned about the horrible history of the Third Reich—the systematic and brutal persecution of political enemies, homosexuals, the disabled, and especially the Jewish community. I saw the Dauchau concentration camp, and what I experienced there was life-changing. I was sick to my stomach as I looked at images and exhibits and heard unspeakable stories of human suffering, pain, and death. I could not wrap my mind around the fact that human beings had committed these unspeakable crimes against fellow human beings for no other reason than their having a different ethnic or religious background, and I could not believe that these people were my own. When I learned that a large part of the German church was either supportive of the Hitler regime or ignored the crimes committed, I became drawn to the history of the Confessing Church.

But the stories from my dad’s side of the family also had a lasting impact. I learned how desperately poor they were and that my father was hospitalized several times for malnutrition, because there was not enough food. Often even children had to work in order for families to survive, which meant my dad missed a lot of school. He and his brothers would walk along the train tracks looking for bits of coal that had fallen off the wagons. “Sometimes,” he told me, “when trains went by, some engineers and operators had compassion for the scrawny kids and dropped a few pieces of coal for them.”

I heard how the community had pulled together to help one another, how allied soldiers, especially GIs, helped out struggling families, often at their own expense. My dad often shared that one of the reasons he didn’t starve to death was an American aid program, and he spoke fondly of the “Quaker” meals he received at school. The U.S. economic program, commonly known in Germany as the Marshall Plan, was largely responsible for the success of the wiederaufbau (rebuilding), which led to the economic miracle in the late 1950s. As a result, I grew up with a very positive image of the United States, even a sense of gratitude.

We are all shaped by the stories of our upbringing, and I believe those stories are at the root of my convictions and values today. I attribute many of my strongest convictions to these formative years, including my commitment to pacifism and a staunch belief that individual conscience takes priority over institutional loyalty.

My belief in the importance of an inclusive church was formed growing up in an evangelical Baptist church that was rather conservative. I remember a lot of good things from my Baptist years. I learned about the love, mercy, and forgiveness of God. But I also remember a certain theology of fear and judgment of the “world” that had an effect on me. One of the biggest questions I had was why I was not allowed to partake in communion. I understand the theology behind it now, but at the time I resented sitting in the pew as the plate and the cup were passed by me. It seemed like such an important moment in the life of the church, and I felt excluded from that holy moment because I had not officially professed Christianity yet. I remember thinking that I was not good enough to be a part of communion.

Because of exclusion I encountered in church as well as in the culture around me, I often felt unworthy to participate, unimportant. It seems a pretty common experience of the Baby Boomer generation. I believe these experiences helped shape my later approach to ministry, with an emphasis that nobody should be made to feel excluded.

So, when I became a minister, I would tell parents, “If you’re comfortable with it, bring your children forward for communion, because they should not feel excluded and should be part of it. Communion is a joyful moment, it is a celebration of our faith, and our children are a big part of that celebration.”

If parents weren’t comfortable bringing their children to communion, I asked them to explain to them why they believed they should wait, and not just exclude them.

My parents still live in Wuppertal. As I child, we did live in a different part of Germany for about three years, and it took me a couple of years to get used to the dialect and the different attitudes and customs. I definitely felt like an outsider during that time. But I always felt accepted and loved by my parents. My dad, Horst, was an engineer before he retired, and my mom, Christel, was an accountant. They provided a home that was deeply religious, caring, and supportive. One of my frequent complaints growing up was, “Do we always have to be the last people to leave church on Sunday mornings?” Many years later I learned that my own kids had the same complaint once I became a minister.

My brother, Uwe, is two years younger than me and, curiously, he also became a pastor and was ordained before I was. I love thinking back to our early childhood years when we were best buddies. Unfortunately, that changed when we became teenagers. Even though our relationship was tainted during those years, I knew that my experience of feeling excluded was nothing compared to his. He probably had ADHD as a child—a condition that was not well understood at that time. Instead of getting the help he needed, he was misunderstood and treated harshly, and he remembers our childhood home as being less happy.

Even though I did not understand what was going on with him and we had our fights, I remember feeling compassion for him in those moments when I felt he was unduly disciplined or rejected. I remember several instances when I put my arm around him to comfort him, and once when I stood up for him against our church’s youth group. It bothered me when he was excluded or threatened with rejection, in part because I knew what it felt like—though to a much lesser degree than he.

After graduating from secondary school and while pursuing an apprenticeship to become an electronics technician, I met my wife. Brigitte visited my youth group at the Baptist church and started to attend the events regularly. I found myself drawn to her instantly, though I think the only reason I got her attention was my passion for playing the guitar, even though my left arm was in a cast at the time. Within three months, we had started to date, and we got married only two years later, on November 28, 1980.

Brigitte was a surgeon’s assistant in a small practice, while I studied electrical engineering. And three years into our marriage, we had our first child, Tim. He was born six weeks premature and with serious medical problems. In fact, his pediatrician told us that Tim would probably not survive the blood poisoning he had developed in addition to his heart problem. Brigitte and I were devastated, but we somehow believed he would come through. We could only touch him through a port in the incubator with surgical gloves. Still, we rubbed his cheeks and his tiny body and talked to him and relied on our faith and the support of our family, friends, and church.

Around this time, Brigitte’s brother and sister-in-law also had their first baby, Suzie, who also had severe medical complications. For much of their first five weeks, Suzie and Tim were in the same hospital room, separated by their incubators. When little Suzie passed away, it was heartbreaking, even while Tim survived and grew strong enough to be able to have open-heart surgery at six weeks. The procedure was successful, and we were so relieved to take Timmy home.

As a parent, I’ve often wondered if there were signs our son would one day turn out gay, but there weren’t. Still, I believe God was already preparing us. Brigitte never really struggled with accepting homosexuality, in part because of her upbringing in a more progressive Christian home.

I, on the other hand, had been taught that homosexuality was a sin, and I accepted that teaching without questioning. That all began to change after I met my wife.

Brigitte’s parents owned a building in downtown Wuppertal-Elberfeld that had about twenty rental units. Helmut and Irene were the first progressive Christians I got to know personally, and I remember being impressed at how nonjudgmental and accepting of others they were.

They practiced what they believed and, as a result, rented their apartments to nontraditional families, including homosexual couples. This is how I met an “out” gay person for the first time. Herr Sieber was one of the renters whom I got to know a little. I remember thinking he was not at all the way I had envisioned homosexuals to be; he was nice and interesting to talk to. I could see myself being friends with him. When Herr Sieber died, from AIDS I believe, I was sad. I remember thinking he was far too young to die. During this time, I started to think about the Bible and homosexuality differently. I became critical of my church’s condemnation of homosexuality. In talks with my friends from church, I remember saying that if it turned out that homosexuality was not a choice, the church was in trouble.

Excerpted from the book DEFROCKED by Frank Schaefer. Copyright © 2014 by Frank Schaefer. Reprinted with permission of Chalice Press.

Guest

- Rev. Frank Schaefer, Methodist pastor and author of "Defrocked: How A Father's Act of Love Shook the United Methodist Church"

This segment aired on September 29, 2014.