Advertisement

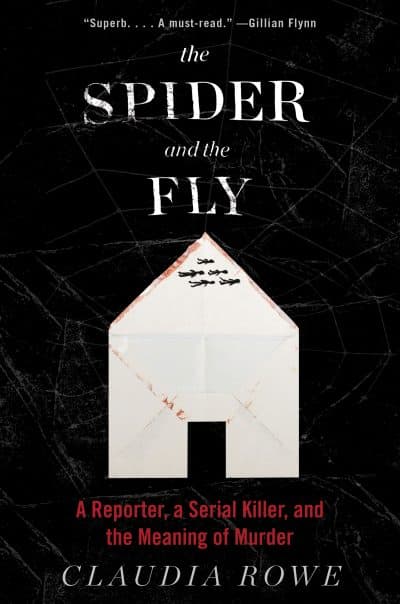

'Spider And The Fly' Delves Into Mind Of A Murderer — And The Reporter Who Covered Him

Resume

In 1998 reporter Claudia Rowe was living in Poughkeepsie, New York, working as a stringer for the New York Times, when she started covering a series of murders committed by a local man named Kendall Francois.

Rowe, at the time struggling with her own demons, wrote a letter to Francois — the first contact in what would become a yearslong quest to find out what could make a man commit the kinds of violent murders to which he confessed, and for which he was eventually convicted.

Rowe writes of the disturbing relationship she developed with Francois, and how her years delving into his life helped her resolve her own issues and move on. Rowe (@RoweReport) joins Here & Now's Robin Young to discuss the story that eventually became the novel "The Spider and the Fly."

Book Excerpt: 'The Spider And The Fly'

By Claudia Rowe

The door to the Pleasant Valley post office pulled against me as if trying to test my resolve. To swing it wide and begin my dutiful march down the white linoleum floor toward mailbox number 1273 required surprising strength. But I did it, as I had all autumn. I trudged past a wall of small steel doors, each little square a portal to someone’s story, identical and indistinct, save for what they held inside: money owed or confessions rendered, forced gestures or pleas unheard, a small universe of private histories locked within those cold metal facings. Boxy and prefab, the post office huddled next to the oldest building in town on a cracked parking lot surrounded by chain supermarkets. Across the street, a feed store and a garage for heavy-equipment repair sat like comfortable old armchairs for the farmers who came into town once a month. But the car dealerships and pizza shops were what blinked loudest to the drivers snaking past in a never-ending line toward somewhere else.

Unpleasant Valley, I liked to call my middle patch of village between the city of Poughkeepsie and Dutchess County’s hunt country estates, reminding myself that I was an interloper here. I’d arrived five years before, hired in 1994 as a reporter for the Poughkeepsie Journal to hound the teachers union and sift school budgets for waste. I quit after twenty-two months, yet remained in town. I could not say why. To friends, I talked of open fields and the country life. But that was only part of the reason. Something about the city of Poughkeepsie, with its melancholy streets and stubborn boosterism, nagged like a blister.

It was November, and I shivered at the stuffy warmth as I walked toward the back of the building. My mailbox was in the last bank of little locked doors, second row from the bottom. A mural painted on the wall opposite showed bonneted farm wives greeting one another in the market square, baskets clutched in the crook of their elbows, implying that Pleasant Valley had once been a bustling village. I slunk past them in disgrace. The only thing I carried was shame, pounds of shame. I was ashamed to be living here, whiling away my thirties. Ashamed to be sleepwalking through life like I was waiting for a wave to pick me up and rush me to the shores of someplace else. Ashamed to have initiated the quest that brought me to the post office every day in hopes of connecting with a figment, a phantom. Week after week, my box remained empty except for a few free circulars, shoved inside like reprimands.

I wondered if the mail sorters pitied me. I could glimpse them behind the wall, their stout shoulders working like levers to slot each envelope into its assigned bin, fingers capped with pink rubber thimbles. They surely knew no letter ever came for number 1273, though it might be worse if one did. I cringed at the thought of anyone recognizing the return address. There would be no blur of bills and magazines to camouflage my correspondent. I had rented this box for one person alone.

In these final weeks of the twentieth century, mail still carried a discreet sensuality. Another person had touched the page you were now holding, had folded and creased it, then slid the rectangle between thumb and index finger, pushed it into an envelope, and licked the gummy backing. That person had pressed the outside flap down and run his finger along the edge. He had held the envelope in his hands, a whisper of the unknown inside, and determined that it should be sent. For this reason, I’d done my best to avoid the postmistress who jawed with customers when they came by at lunchtime to pick up their packages. But now I was prepared. I’d practiced my pitch, sitting amid the crumpled coffee cups and rotting newspapers in my car. I needed to close my mailbox, cancel my account, and get a refund for the remaining four months of my rental, I’d say. I earned near-poverty wages as a stringer for the New York Times, so a hundred wasted dollars hurt. None of these flinty folk were likely to question the need to save money. They drove rusty trucks and salt-pocked American cars, though their family names dotted my county road maps. Whatever the manager said, this would be my last visit to the Pleasant Valley post office. I was worn out writing to someone who never wrote back.

At the beginning I’d been almost jaunty about this project, as if it were a game I knew I’d win. As if all I had to do was swing by and collect my prize. That vain assumption dissolved into confusion after a second letter met with continued silence. Now the feeling verged on humiliation. My chest was hollow with the ache of ridiculousness as I slid my key into the lock for one last look. I would pull out a final round of inky coupons, dump them in the overflowing garbage can, and be done.

But no. Lying inside the narrow steel slot was a single cream- colored envelope, the paper stock textured and substantial. I paused, staring at my name and address scrawled in rounded cursive across the front. Shaking just a bit, I tore it open.

Mrs. (Ms.) Claudia Rowe

Greetings, I would like to thank you for your letter, but you know as well as I do that you don’t want to be my friend. You want a story. I’m feeling generous, so if your on the ball this may be your lucky day. I don’t need to make friends with some one that will later betray me. So here is the deal.

I want to know everything about you, everything. For every ten pages (typed) I will answer ANY four questions you have for me, completely and honestly. So twenty pages gets you eight questions, but nineteen only gets you four.

I will answer your questions with the completeness and honesty you answer me. I want to know about your hometown, childhood house, elementary school and high school up through college, your first car, your first kiss, the dress you wore under your graduation gown, I want to know the first time (if ever) you gave a guy a blow job, the first time you had intercourse, the last time, people you hate at work, affairs, when (if ever) you dyed your hair, the types of computers you have/use. Remember the more details the better.

This isn’t an article for a newspaper so don’t write it like it is. It should have some heart, a spark. If it is cold and indifferent I may think you’re lying. If I think it is a lie there will be no response.

Good evening!

Kendall Francois

The two pages of legal-sized paper were covered top to bottom, from the left margin all the way to the edge of the opposite side. The handwriting was concentrated, childlike, but each word had been carefully formed and there were no cross-outs or squeezed- in afterthoughts. It suggested someone working with great determination and control. I read the letter once standing in the back of the post office, then drove home, shoved it under a stack of books, and did not touch it again for two weeks.

Excerpted from the book THE SPIDER AND THE FLY by Claudia Rowe. Copyright © 2017 by Claudia Rowe. Reprinted with permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of Harpercollins Publishers.

This segment aired on January 25, 2017.