Advertisement

The Stories And Symbols Behind The Flags Of The World

Resume

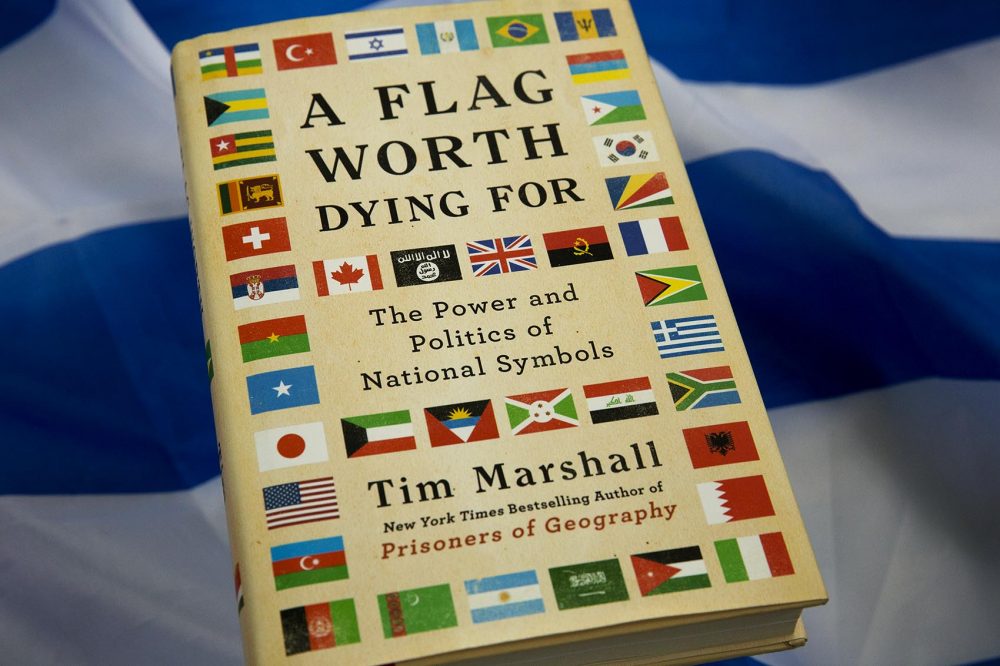

What does a flag say about the country that flies it? Journalist Tim Marshall looks at the stories behind dozens of the world’s flags in the new book “A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols.”

Marshall (@Itwitius) joins Here & Now's Peter O’Dowd to talk about the book.

Book Excerpt: 'A Flag Worth Dying For'

By Tim Marshall

"I am no more than what you believe me to be and I am all that you believe I can be." — The American flag in a conversation as imagined by Franklin K. Lane, US secretary of the interior, Flag Day, 1914

On 9/11, after the flames had died down and the dust had mostly settled, three FDNY firefighters clambered onto the still-smoking wreckage of the World Trade Center in New York City and raised the Stars and Stripes.

The event was not planned, and there were no official photographers; the three men just felt that amid such death and destruction, they should do “something good.” A local newspaper photographer, Tom Franklin, captured the moment. Later he commented that his picture “said something to me about the strength of the American people.”

How could a piece of colored cloth say something so profound that the photo was reproduced not only across the United States but in newspapers around the world? The flag’s meaning comes from the emotion it inspires. Old Glory, as the Americans know it, speaks to them in ways that a non-American simply cannot share. Non-Americans, however, can understand this, because many have similar feelings about their own symbols of nationhood and belonging. You may have overtly positive, or indeed negative, opinions as to what you think your flag stands for, but the fact remains: that simple piece of cloth is the embodiment of the nation. A country’s history, geography, people, and values—all are symbolized in the cloth, its shape, and the colors in which it is printed. It is invested with meaning, even if the meaning is different for different people.

Each of the world’s flags is simultaneously unique and similar. They all say something—sometimes perhaps too much.

That was the case in October 2014 when the Serbian national soccer team hosted Albania at the Partizan Stadium in Belgrade. It was Albania’s first visit to the Serbian capital since 1967. The intervening years had witnessed the Yugoslav civil war, including the conflict with the ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. That ended in 1999 with the de facto partition of Serbia, following a three-month NATO bombing of Serb forces, towns, and cities. Then, in 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared itself an independent state. The move was supported by Albania and recognized by many countries; Spain, notably, was one that did not. It understood that the sight of the Kosovar flag flying above the capital of an independent Kosovo might galvanize the Catalonian independence movement.

Fast-forward six years, and tensions between Serbia and Kosovo, and by extension Albania, were still high. In the certain knowledge that they would be attacked, away fans had not been allowed to attend.

It was a slow-paced game, albeit with a highly charged atmosphere, punctuated by loud chants of “Kill the Albanians” ringing out from the stands. Shortly before halftime, fans and then some players began to notice that a remote-controlled drone was approaching slowly out of the night sky toward the halfway line on the playing field. It was later discovered to have been piloted by a thirty-three-year-old Albanian nationalist called Ismail Morinaj, who was hiding in a tower of the nearby Church of the Holy Archangel Gabriel, from where he could see the field.

As the drone flew lower, a stunned silence began to descend around the stadium and then, as it hovered near the center circle, there was a sudden explosion of outrage. It was carrying an Albanian flag.

This wasn’t merely the flag of the country, which alone would likely have caused problems. This flag bore the double-headed Albanian black eagle, the faces of two Albanian independence heroes from the early twentieth century, and a map of “Greater Albania,” incorporating parts of Serbia, Macedonia, Greece, and Montenegro. It was emblazoned with the word autochthonous, a reference to indigenous populations. The message was that the Albanians, who consider themselves to be of ancient Illyrian origin from the fourth century BCE, were the real people of the region— and the Slavs, who arrived only in the sixth century CE, were not.

A Serbian defender, Stefan Mitrovic´, reached up and grabbed the flag. He later said he began folding it up “as calmly as possible in order to give it to the fourth official” so that the game could continue. But two Albanian players snatched it from him, and that was that. Several players began fighting with each other; then a Serbian fan emerged from the stands and hit the Albanian captain over the head with a plastic chair. As more Serbs poured onto the playing field, the Serb team came to their senses and tried to protect the Albanian players as they ran for the tunnel, the match abandoned. Missiles rained down on them as the riot police fought fans in the stands.

The political fallout was dramatic. The Serbian police searched the Albanian team’s dressing room and then accused the brotherin-law of the Albanian prime minister of operating the drone from the stands. The media in both countries went into nationalistic overdrive; Serbia’s foreign minister, Ivica Dacˇic´, said his country had been “provoked” and that “if someone from Serbia had unveiled a flag of Greater Serbia in Tirana or Pristina, it would already be on the agenda of the UN Security Council.” A few days later, the planned visit of the Albanian prime minister to Serbia, the first in almost seventy years, was cancelled.

George Orwell’s aphorism that soccer is “war minus the shooting” was proved right, and, given the volatility in the Balkans, the mix of soccer, politics, and a flag could have led to a larger conflict.

Planting the US flag at the site of the Twin Towers did presage a war. Tom Franklin said that when he took his shot, he had been aware of the similarities between it and another famous image from a previous conflict, World War II, when US Marines planted the American flag atop Iwo Jima. Many Americans recognized the symmetry immediately and appreciated that both moments captured a stirring mix of powerful emotions: sadness, courage, heroism, defiance, collective perseverance, and endeavor.

Both images, but perhaps more so the 9/11 photograph, also evoke the opening stanza of the American national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” particularly its final lines:

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

At a moment of profound shock for the American people, the sight of their flag yet waving was reassuring for many. That the stars of the fifty states were held aloft by men in uniform may have spoken to the streak of militarism that tinges American culture, but to see the red, white, and blue amid the awful gray devastation of Ground Zero will also have helped many ordinary citizens to cope with the other deeply disturbing images emerging from New York City that autumn day.

* * *

Where did these national symbols, to which we are so attached, come from? Flags are a relatively recent phenomenon in human history. Standards and symbols painted on cloth predate flags and were used by the ancient Egyptians, the Assyrians, and the Romans, but it was the invention of silk by the Chinese that allowed flags as we know them today to flourish and spread. Traditional cloth was too heavy to be held aloft, unfurled and fluttering in the wind, especially if painted; silk was much lighter and meant that banners could, for example, accompany armies onto battlefields.

The new fabric and custom spread along the Silk Road. The Arabs were the first to adopt it, and the Europeans followed suit, having come into contact with them during the Crusades. It was likely these military campaigns, and the large Western armies involved, that confirmed the use of symbols of heraldry and armorial markings to help identify the participants. These heraldic bearings came to be linked with rank and lineage, particularly for royal dynasties, and this is one of the reasons European flags evolved from being associated with battlefield standards and maritime signals to becoming symbols of the nation-state.

Every nation is now represented by a flag, testament to Europe’s influence on the modern world as its empires expanded and ideas spread around the globe. As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe told the designer of the Venezuelan flag, Francisco de Miranda, “A country starts out from a name and a flag, and it then becomes them, just as a man fulfils his destiny.”

What does it mean to try to encapsulate a nation in a flag? It means trying to unite a population behind a homogeneous set of ideals, aims, history, and beliefs—an almost impossible task. But when passions are aroused, when the banner of an enemy is flying high, people flock to their own symbol. Flags have much to do with our traditional tribal tendencies and notions of identity—the idea of us versus them. Much of the symbolism in flag design is based on that concept of conflict and opposition—as seen in the common theme of red for the blood of the people, for example. But in a modern world, striving to reduce conflict and promote a greater sense of unity, peace, and equality, where population movements have blurred those lines between “us and them,” what role do flags now play?

Excerpted from A FLAG WORTH DYING FOR © 2017 by Tim Marshall, Reprinted with permission from Scribner.

This segment aired on July 3, 2017.