Advertisement

Researchers Memorialize First Major Icelandic Glacier Lost To Climate Change

Resume

Scientists, academics and world leaders will soon gather in Iceland to memorialize the first major Icelandic glacier to disappear due to climate change.

Okjökull — "Ok glacier" in Icelandic — was deemed “dead” in 2014 because it had lost so much ice.

“It didn't have enough mass of snow and ice in order to be able to crawl along the ground which is required of a glacier to be able to move under its own weight,” says Cymene Howe, an associate professor of anthropology at Rice University.

Now, scientists are installing a memorial plaque on the barren ground as a message to future generations. Howe will be in attendance, along with geologist Oddur Sigurðsson, who first declared the glacier dead.

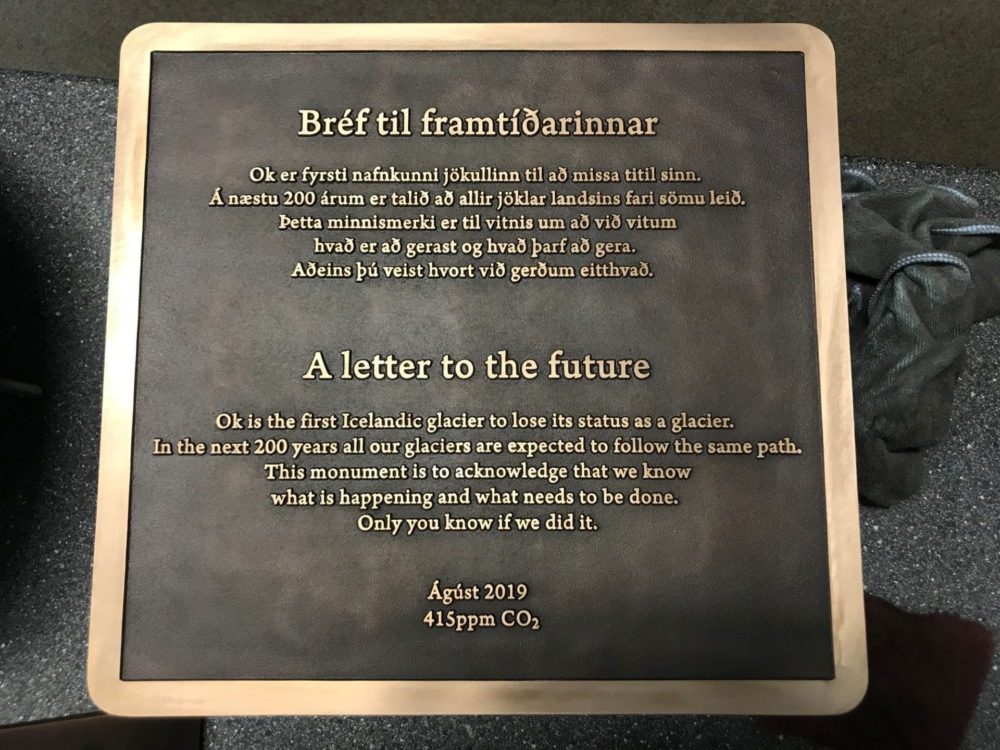

The plaque, called “A letter to the future,” reads in both English and Icelandic: “Ok is the first Islandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Howe says the plaque’s direct messaging was intentional. The team of researchers wanted to use the glacier’s passing as a call to climate action.

“By memorializing a fallen glacier, we want to emphasize what is being lost or what is dying,” she says. “And we also want to draw attention to the fact that climate change is also something that humans have accomplished, if you will, although it's not something that we should be particularly proud of.”

Interview Highlights

On whether there’s any ice left on Okjökull

“Well that's a good question because actually this will be the first time that the glaciologist who declared Ok glacier — Okjökull — to no longer be a glacier will be going up on top of the mountain to see if there is any glacial remnant ice remaining. His name is Oddur Sigurðsson and he was the scientist who found that Ok was no longer able to move under its own weight.

“So it's exciting because this will be the first time that he's back to inspect what might remain of Ok glacier. They call it glacial remnant ice. And so part of our trek there — after we install the plaque and the memorial and have a small ceremony — is that we will head over to the top of the crater and then descend down the backside to see if we can find any ice remaining.”

On the memorial ceremony

“It's interesting because we had lots of conversations to think through how we wanted to mark this passing of the glacier. And there is a couple of different options, right. We could have done a kind of headstone or a grave marker and that would have sent a certain message of loss and memorial. We also could have done a more scientific plaque like you might find in a national park with all the details about Ok. We decided to do a memorial very specifically because if we look around the world, we can see that memorials everywhere stand for either human accomplishments, like the deeds of historic figures, or the losses and deaths that we recognize as important, like on a battlefield memorial.”

On why researchers decided that the plaque should explicitly address future generations

“Well the future generations was also very intentional and there's a kind of title on the memorial. It says 'A letter to the future' and the words were created by our Icelandic colleague Andri Snær Magnason. He's an author and a poet. And so we wanted to work with an Icelander to craft the words so that they would be appropriate to the place.

“I think of the last line, 'Only you know if we did it,' as a kind of call to action to become involved and to try and reduce the amount of anthropogenic harm that we're doing to the climate and to the atmosphere. Saying 'Only you know if we did it,' I think, is a very powerful way of phrasing it because the second person plural form — the 'you' form — is a very direct way of speaking to people. When reading the plaque, you can literally imagine this future person standing there reading over this memorial. And so by addressing this letter to the future, by invoking the you, we're trying to very explicitly draw attention to that potential and that future.”

On why researchers added a reference to current CO2 levels, which is at 415 parts per million

“Well we felt that was really important to acknowledge. In spring of this year, we passed that threshold of 415 parts per million. So this is the first time that human beings have ever lived with that quantity of atmospheric carbon dioxide and content in the atmosphere. So last time we had that much CO2 in the atmosphere was during the Pliocene, which was about 3 million years ago before we had humans on the planet. And so it's a very dramatic reckoning to think through the fact that we're living in conditions that we humans have never actually lived in before. The other element of course is that as the future viewer of this plaque looks at that number, a year from now, 10 years from now, 100 years from now, that number will probably be higher. So that's a reckoning as well.”

Ashley Locke produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Kathleen McKenna. Serena McMahon adapted it for web.

This segment aired on August 16, 2019.