Advertisement

Refuge

Resume

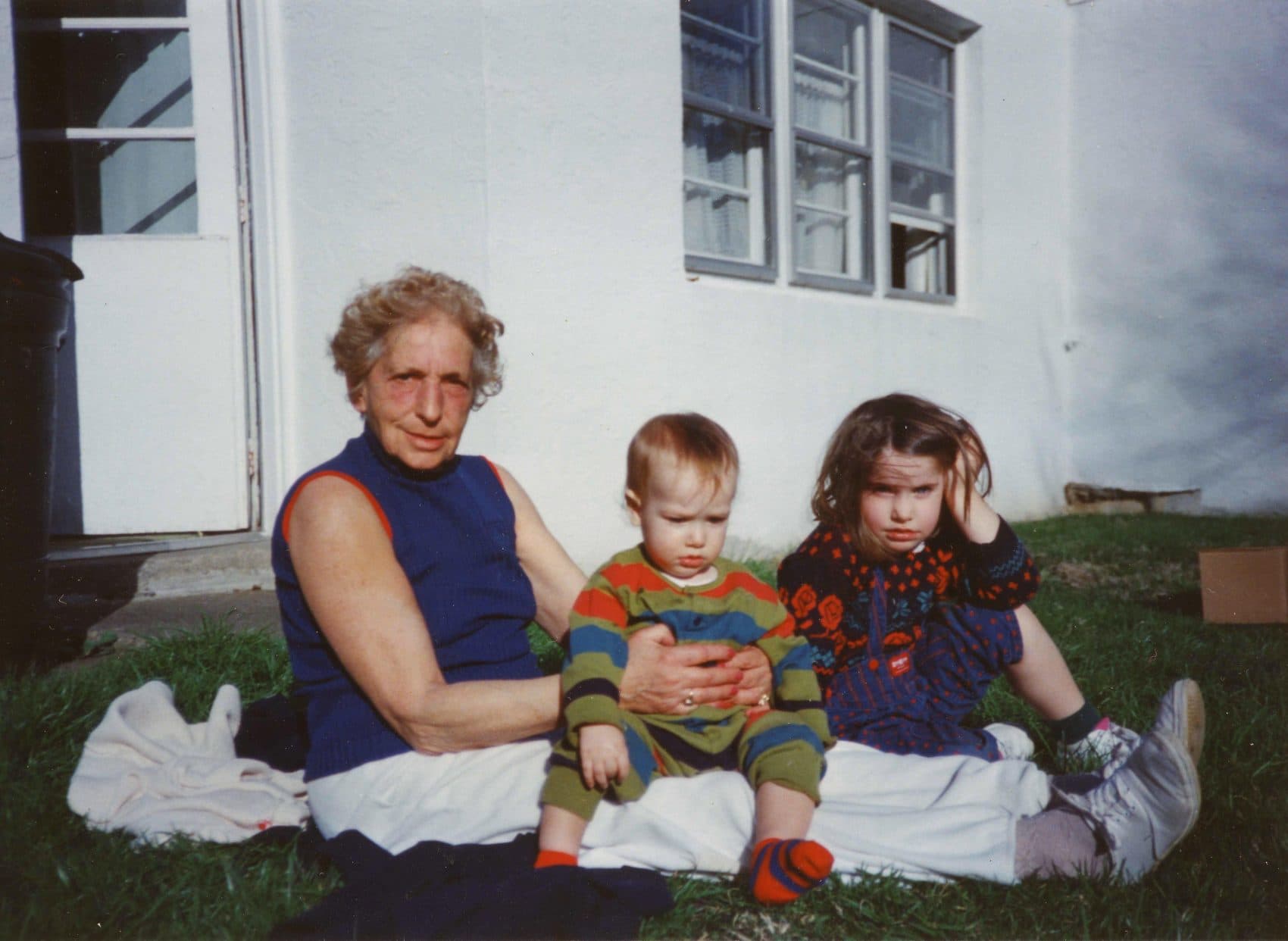

Rachael Cerrotti grew up in Boston, and she remembers the day she she started to feel like an adult. She was a college student and visiting her grandmother, Hana Dubova, outside of Philadelphia.

“She had this box of wine, and it was only slightly expired red wine, so we each poured a cup,” Rachael remembers.

They sat on Hana’s porch overlooking a parking lot. They were there because Rachael wanted to hear her grandmother’s story. She knew some parts already; her grandmother was a Jewish Holocaust survivor from Czechoslovakia.

“My grandmother had so much to say, but I don’t think that many people asked her questions,” Rachael says.

So Rachael started asking. Over the next year, the two of them sat down regularly for oral histories, Hana talking and Rachael taking notes.

Hana’s health deteriorated that year. Their conversations moved from the porch to Hana's bed, as she found it difficult to move, and in 2010, at the age of 85, Hana died. She left behind a mass of diaries, letters and photographs, and Rachael became obsessed with digging deeper into her grandmother’s past.

Rachael decided to spend the coming years retracing her grandmother’s footsteps. She wanted to find the people and places in Hana's stories, recreate Hana's journey as closely as she could, and photograph what she found. The project has consumed eight years and altered the course of Rachael's life more than she ever expected.

Rachael's grandmother Hana was born in 1925 in Czechoslovakia. Her father owned a shop on Prague’s main square when Hitler came to power.

“They thought that it could never happen here, that antisemitism was just a rumor,” Rachael says. “By the time they realized it could happen here, it was too late. ... Nobody wanted these refugees, soon-to-be refugees.”

Hana told Rachael that her family applied to come to the U.S. without success. Then came a sliver of hope.

“The Danish government agreed to take in a set number of Czech Jewish children between the ages of 14 and 16 and put them on foster farms in Denmark, and Hana was chosen.”

Soon 14-year-old Hana was at a train station saying goodbye to her family. She thought the war would be over soon. She didn’t know that within a few years, her parents and her little brother would be murdered in an extermination camp.

When Hana arrived in Denmark, the Danish program placed her on three foster farms that hosted her for six months each. The idea was that she would work on the farm in exchange for a safe place to live.

“She went from being a child to being a servant overnight,” Rachael says. “For the first two farms that Hana was on, she was with families that she felt like didn’t treat her well. ... She wasn’t allowed to eat with the family. She had to live upstairs in the attic that was unheated. She wrote about her sheets freezing in the night.”

But everything changed when Hana moved in with a young couple and their baby.

“This third foster family, they treated her like family,” Rachael says.

For the first time in ages, Hana found herself skipping and singing.

“In her letters, she talks about all of a sudden feeling at home, and she hadn’t said that in years,” Rachael says.

So, decades later, Rachael tracked down that family, and she asked to live on the farm of their descendants, just as her grandmother had.

The farm belonged to Sine Christiansen and her husband, Torsten Christiansen. Sine’s grandmother had hosted Rachael’s grandmother 74 years before.

“We all knew the story, but it became different when I met Rachael,” Sine says. Her grandmother had often worried about what had happened to the refugee from Czechoslovakia after they lost touch.

Rachael moved in and helped Sine with farm work every morning, just as their grandmothers had done. They spent hours in conversation on the windswept farm.

“We talked about our grandmoms, and we started to feel a little connected or in family or something because of their connection,” 42-year-old Sine says. “I think they had a special bond.”

They laughed, they cooked, they even sang together, and gradually Rachael felt like one of them.

“I'm reading words that my grandmother wrote about this family from 1941,” she says, “and it's like I could take those words and put them into my diary today about their descendants.”

Rachael’s grandmother Hana was able to stay in Denmark safely until she was 17, when a stranger on a bicycle appeared. He was part of the Danish underground, and they’d heard that Nazis were about to round up Jews in the area. He told her she needed to leave immediately, so she got on her bike and followed him to a church.

The man on the bicycle hid her in a church attic for three days, until, one night, a fisherman smuggled Hana and more than a dozen other refugees to Sweden by hiding them under piles of herring in his boat.

“That piece of her story has affected me in so many ways,” Rachael says.

“We hear about all these horrific details over and over again, but there are these stories that compete with that, where it’s like, yeah, but look what you can do that can save people. It’s a really different story than friends of mine whose grandparents were in concentration camps. Hana was never in a camp, because people kept her safe — because people honored her life as a human.”

For Rachael, history keeps circling back to the present.

In 2016, as part of her research, she visited the place where the fisherman’s boat landed in Sweden. She found a surreal scene: young refugees living without their parents in the same building that Rachael’s grandmother stayed in during her first night as a refugee in Sweden.

“One day, those kids who are finding refuge in Sweden are going to be grandparents,” Rachael says. “Either we give them a narrative to tell their grandchildren about how people were wonderful and helped us and treated us with respect and kindness, or we can hand them a narrative about hate and fear.”

For her part, Rachael is still close with the people who helped her grandmother. In 2016, when she got married, she celebrated the wedding at Sine’s farm with the descendants of the people who gave Hana a home. By then, they had long felt like family.

“I remember Sine turning to me and saying, ‘I think our grandmothers are smiling down at us.’ That’s just what it feels like,” Rachael says. “The beauty that’s come out of such tragedy has become perhaps the most important part of my grandmother’s story.”

Rachael has spent her entire adult life in her grandmother’s past, and the deeper she goes, the more she finds hope for the present.

One mother after that wedding celebration in Denmark, something would happen that would change everything for Rachael. We tell that story in the next episode of Kind World.

This story is the second part of a series produced in collaboration with WBUR’s Cognoscenti. Find Part 1 and Part 3 for the full story.

You can follow Rachael Cerrotti as she retraces her grandmother's journey and learn more about her project here. This episode includes music by Blue Dot Sessions (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Find Kind World on Facebook or Twitter, or email kindworld@wbur.org to share your story. You can also subscribe to the podcast.

This segment aired on December 5, 2017.