Advertisement

The 'Monstrosity' Health Care System: 3 Problems, 1 Vermont Solution

Sometimes when I think about the American health care system, I want to cry. It's so hopelessly Byzantine, so dysfunctional, so exorbitant compared to other developed countries.

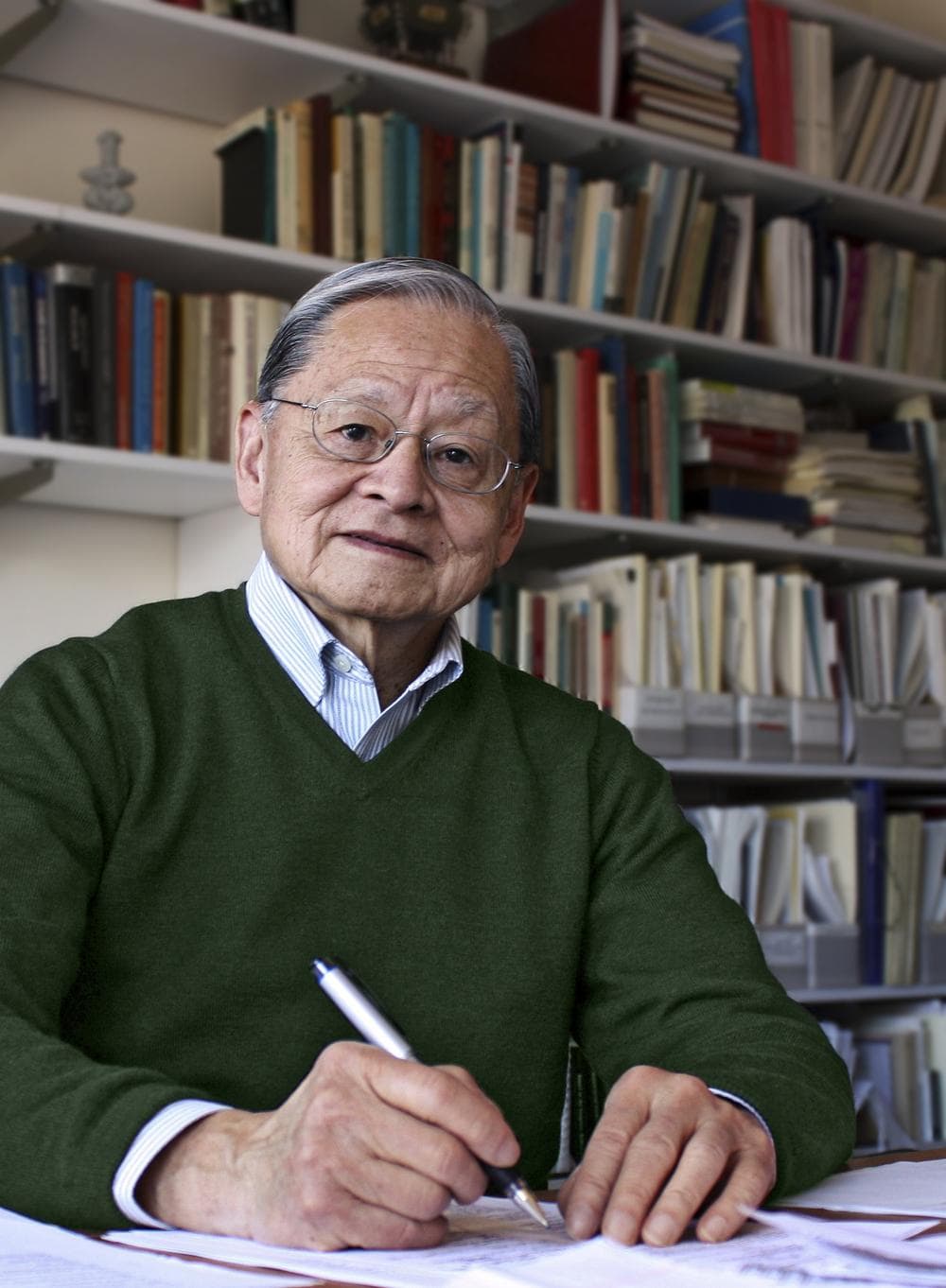

But it was oddly comforting to listen to Harvard's William Hsiao, one of the country's leading health care economists, speak last night at Brookline's 16th annual Public Health Policy Forum. He has a gift for distilling down the complexity and making it all seem less hopelessly tangled — and what happens now in Vermont, where he's helping to engineer the historic push toward a single-payer system, will show whether he's right. Here, nearly verbatim — because he inspired me to try to type his every word — is what he said:

The American health care system has three major problems:

1) The uninsured

2) Quality of care

3) Affordability and rapid cost escalation.

If you were in President Obama's shoes, how would you solve this?

I'd like to argue that the problem is systemic. It's not one problem. There are several very fundamental causes all linked together, creating these three phenomena that we call problems. So what are these causes and how is Vermont attempting to solve these fundamental causes?

The first cause: Our health insurance is linked to employment, so if you're not employed, or your employer does not offer insurance, you're out of it. Basically, all advanced economies have moved away from that. We're one of the few remaining to tie our health insurance to employment.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]We've created a monstrosity of administrative complexity.[/module]

Secondly, we rely on many insurance funds — public or private, for-profit or non-profit — to insure people. We have a patchwork, so consequently you can do risk-selection: If I'm an insurance company, I would not want to insure anyone with gray hair like mine. I’d want to go to Silicon Valley and insure healthy young people. We created an insurance system that encouraged insurance companies to exclude the less healthy people and only insure the healthy.

Administrative hassle

Third, because we have so many insurance companies, everybody — doctors and nurses and nurse practitioners — has to deal with each one differently. We call that competition. We call that pluralism. What happens then? If you’re a practitioner, you’re going to spend your time dealing with multiple insurance companies. This is what doctors call "administrative hassle."

On average, a solo practitioner usually deals with eight insurance companies and every insurance company usually has three or four different plans.

On average, a solo practitioner has to spend five or 10 percent of their time dealing with insurance; usually a nurse spends a third of her time dealing with it. Plus an average doctor employs one clerk, to deal with insurance forms. We've created a monstrosity of administrative complexity. Well, maybe that’s the Employment Act of 1990. So we have multiple insurance companies with multiple rules tying up the hands of the doctors and hospitals with different payment rates. And then what do the hospitals and doctors do? They strategize about trying to get the best rates from the insurance companies.

Also, we have a fragmented health care system. Our health care delivery was established back 50 or 80 years ago when diseases were episodic, and we were confronted mostly with infectious diseases. But now, most of us, myself included, suffer from chronic illness. We need continuous care, including from prevention all the way up to hospitalization if we have acute episodes. But our system is separated at every level. Consequently, doctors repeat the same tests, ask you the same questions, they do not know what drugs you’re taking so they give you some other drugs and cause drug toxicity and complications.

The systemic solution

So we have a systemic problem in the United States and meanwhile, most of our solutions are patchwork. There’s a problem, put a Band-aid on it. And political leaders say, 'As long as I can make it through my term, I'll leave the problem to the next term.'

So what is Vermont trying to do? Vermont is a progressive state. It has the ambition to be a vanguard for the USA, to be a laboratory, and if it works in Vermont, it will show what could be done. Then it's up to the other states or the federal government to replicate it.

Vermont asked me to organize a team, and the simple reason is this: They want to depoliticize the whole process. So if an outside group with no vested interest comes in with a plan, then people can attack the plan but they cannot say 'This is Democrats or Republicans — or Communists.'

1) So the first thing we did in the Vermont single-payer plan is to decouple insurance from employment. All legal residents of Vermont will be automatically covered.

2) Single-payer means there's only one insurance plan, not dozens of insurance companies operating. There's only one insurance fund, so you pool the risk of the young people and old people together, the healthy and the unhealthy people, rather than having it segmented like right now. So it removes so-called risk selection.

A single pipe

3) Third is, once you have a single insurance fund, then you create what we call a single pipe. Think of water faucets: If there are a dozen water faucets letting out water and you’re trying to control that flow, you'll have a tough time. But if you have a single faucet you can control that flow more exactly and precisely and in a more timely way.

Single-payer means only a single type of payment. If you're a provider you only deal with one insurance payer with one set of rules, and you cannot game them. You cannot do cost-shifting. And single payer allows you to create a comprehensive database — you can compile a profile for every patient and doctor and see who is committing fraud and abuse.

Taiwan did that. To our surprise, they found that 90 percent of doctors and hospitals are really good. But roughly 8 to 10 percent were abusing the system. They cracked down. In the first year, they saved 8 percent of the total health care costs in Taiwan. If you think that’s high, think of FBI estimates: They estimate that 3-10 percent of health care expenditures in the United States are fraudulent — not just abuse, fraud. But we cannot catch them because the data is scattered among many insurance plans.

We did a simulation of the single-payer model, and found that over time, you can reduce health care costs by 25 percent. That means for the whole US you could save $5-600 billion each year. Even if you don't implement it perfectly you could still save half of that. That’s still $300 billion. We’d use those savings to cover everybody. We recommend financing the health insurance benefit plan through a payroll tax, and we're sure the payroll tax could save money for employers and workers because of this 25-percent reduction in costs.

We have a systemic problem. It’s up to us to find a systemic solution.

(For more on the Vermont single-payer plans, listen to this excellent Radio Boston segment, which includes an interview with Vermont governor Peter Shumlin.)

This program aired on June 23, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.